This post was made possible thanks to a phenomenon I call “twitterdipity.”

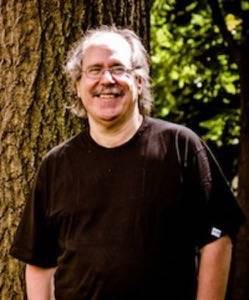

Twitterdipity is the experience of wading in Twitter’s shallow, fast-moving data stream and suddenly – and surprisingly – mining treasure from a tweet. It’s casually catching the eye of good fortune in a speed-of-light culture. It’s when you score a free ticket to an exclusive event or click a game-changing link at just the right time. My most recent (and exciting) experience of twitterdipity happened when I tweeted that I was reading Paul Levinson’s book Digital McLuhan and then the award-winning sci-fi writer, singer/songwriter, communications professor and oft-interviewed media ecologist decided to follow me. Me!

Guest author Michelle Anderson is a storyteller, media ecologist and community builder for hire. She goes by the moniker @mediaChick on Twitter and just about everywhere else, as well. She is the creator and author of The Miracle in July, an ambitious, genre-busting storytelling experiment seeking to redefine what “success” means in today’s global theater. Through teaching, consulting, speaking and publishing, Michelle hopes to inspire storytellers world-wide to experiment with social media ecology in their work. She also bakes one hell of a pie.

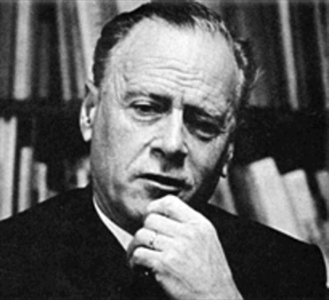

As a rogue media ecologist, I play scholarly voyeur on the Media Ecology Association’s mailing list. Over the years I’ve passively learned the intricacies of the interdisciplinary study of the ecosystems of media by eavesdropping on riveting academic discussions. The ones that interest me the most are the endless conversations about Marshall McLuhan, the cutting-edge communications and media theorist who coined phrases such as “global village” and “the medium is the message.”

It was from studying McLuhan that I realized that the word “medium” was meant to include roads, electricity and assembly lines as well as broadcast television and the telegraph. I realized that it is the form of a medium, rather than its content, that molds and shapes our view of the world, and that the “message” of the medium is the change in the pattern of humanity. But it is McLuhan’s famous 1962 declaration in The Gutenberg Galaxy that “the new electronic interdependence recreates the world in the image of the global village” that got me thinking about the conditions that conjure twitterdipity.

Appropriately enough, from this media ecologist’s point of view, it is Twitter’s ecosystem that breeds these wonderful moments of twitterdipity. The choice in following (or not following or blocking) a tweeter leads to the customization of Twitter’s indiscriminately rich fire hose of data; it makes for a fertile, personalized climate.

Conditions for Twitterdipity

Content published from a world-wide, realtime community of incredibly diverse producers and consumers, who all have access to the same high-volume channels in which to influence others and attract the influential, seeds potential twitterdipity moments. Add to this environment the natural affinity for the brain to treat online and offline social interactions exactly the same – creating the same feelings of empathy and rivalry and social pressure to maintain a community decorum – and you’ve got yourself conditions ripe for twitterdipity.

Take, for instance, the twitterdipity environment that created this post:

I tweeted that I was reading Paul Levinson’s book Digital McLuhan – a key book in my education of how McLuhan’s ideas work in the Digital Age.

Paul Levinson saw the tweet. He saw my bio. ( I called myself a media ecologist and a “bliss follower.”) He decides to follow me.

I worked up the nerve to ask Levinson – a man who’s been interviewed by damned-near everybody, including Bill O’Reilly in a fun boxing match about the mass broadcasting of beheadings, and whose 1972 pychedelic folk rock album “Twice Upon a Rhyme” still appears on cult collector’s lists – to answer 5 questions for a post.

Levinson agreed. I smiled like crazy for days.

So, what five questions does a rouge media ecologist ask her academic hero, the award-winning sci-fi writer, singer/songwriter, communications professor and oft-interviewed Paul Levinson? These five questions:

Anderson: McLuhan’s 1960 “global village” concept includes a tribal environment prone to discord and disagreements due to the invention of worldwide, real-time interconnectivity of electric technology. Yet, in 1966 he said at an author’s luncheon in New York, “The satellites, as a new garbage or climate surround around the planet, are moving information at speeds that the planet can not cope with and have created not a global village but a Global Theater. I no longer use the phrase global village. It’s global theater now, and everybody out here, and me too, we’re all out to do our thing. Jobs are finished, jobs are over, role-playing comes in.” (Hear McLuhan say this at the 3:36 mark.) McLuhan’s “global theater” idea involves a global village in which everyone acts as both producer and consumer, actor and spectator. So, why do you think that the temperamental “global village” concept is the one that is commonly referenced as McLuhan’s predictive metaphor for the Internet rather than the everyone-as-content “global theater” concept?

Levinson: I think 99% of the ascension of global village over global theater has to do with the homespun, populace appeal of village in contrast to the haute, upper-crust vibes of theater. Most people don’t go to the theater anymore – or, if they do, it’s to see their kids in a high school play. In either case, theater is far more specialized than village. Also, the village is a antonym to global, which gives the metaphor tension, in contrast to global theater, which sounds like something out of Shakespeare. The 1% is that global village had already caught on by 1966.

Anderson: (That was a long question. Here’s a short one!) What do you predict will be the long-term effect of the social web (which is becoming an “equalizer” of sorts) on the offline world in terms of access to information and influence?

Levinson: The long-term effect will be that governments, corporations, universities, elite media will find it increasingly difficult to dole information out on their own terms. Information will be out there for everyone, all the time, anywhere they and the information may happen to be. Further, as I detail in my New New Media (2009), all receivers and consumers of information will become producers – anyone can set up a Facebook page, upload a video to YouTube, Tweet 20 hours a day. This means that the difference between professionals and amateurs – between those whose profession it is to produce versus those who produce for love – is becoming less and less. Anyone can write and edit on Wikipedia, and a survey in Nature Magazine a few years ago found no difference in error levels in the Encyclopedia Britannica and Wikipedia. We come from a world in which gatekeepers decided what the rest of us could see and hear in our media. With the advent of new new media, the gatekeepers are leaving their positions, and the playing field of significant public communication is open to everyone. This is a great step forward for freedom and democracy.

Anderson: Since the very first modem whine, the Internet has been the perfect environment for groups to propagate. With its infinite space and real-time communication, today the Internet sustains countless communities, ranging from metropolitan and bustling to rural and quiet, and more are forming every day. What are your thoughts on the role of the relatively new career of Online Community Manager, a position created to build and manage groups of digital personalities that are joined together under a common interest or goal?

Levinson: My opinion is the Internet is not about empowerment of new leaders, it is about the empowerment of everyone. The idea of an Internet professional community leader is an oxymoron. Leaders arise without training, and survive or not based on their performance, not their credentials, in the new online world.

Anderson: In 1972, McLuhan participated in a debate on the subject “Do books matter?” by giving a speech which he called “The Future of the Book” (Understanding Me, 2003). “The book is not moving towards an omega point,” he said, “but is actually in the process of rehearsing and re-enacting all the roles it has ever played, for new graphics and new printing processes invite the simultaneous use of a great diversity of effects.” Do you think McLuhan was talking about a new technology (Kindle, Vook, iPad), or a new process in which we define what a book is (a new technology-neutral format)?

Levinson: I think McLuhan was talking about the Internet, without giving it that name, back in 1972. His view of this new “book” is something I explore in Digital McLuhan, where I point out that the Internet is the media of media. Kindle, iPad, etc. have this same quality.

Anderson: Thanks to innovative digital strategies from Wieden + Kennedy, one of the top brand agencies in the world, the brand Old Spice recently enjoyed a 107% increase in sales. The campaign’s raging success also created a new benchmark for large agencies who wish to convince their traditional media-minded clients that using inexpensive (even free!) social media tools in their ad campaigns can be very lucrative. What do you see as the fall-out from this adoption of the social web by “big money” agencies for individual producers and consumers of online content, as well as the smaller Internet marketing firms who specialize in digital strategy?

Levinson: The age of Madison Avenue style advertising – what we see aborning on “Mad Men” – is coming to an end. Rather than advertise on traditional media such as television and billboards, campaigns of the future will be closer to what my namesake (but no relative) Jay Conrad Levinson calls “guerrilla marketing.” The advertising campaigns of the future will be increasingly waged in the jungles and dirt roads and nooks and crannies of the Internet – all of which may be more direct routes to our minds than looking at a television.

“The Empowerment of Everyone”

With instant access to everything all the time, our global village has little patience with high-gloss, slick campaigns where consumables are layered with glitz to hide mediocrity within. In a village, everyone knows everyone else’s business – their strengths, weaknesses, triumphs and failures – which creates the “equalized” playing field that Levinson described as “a great step forward for freedom and democracy.” A global village, one that pairs the oxymoronish intimacy of village life with a worldwide web of connectivity, can then lead to a once-impossible moment of twitterdipity, where an up-and-coming media ecologist in Portland, Oregon can pick the brain of a world-renowned and award-winning author, professor, and media environment expert from the East Coast. As Levinson noted, “the Internet is not about empowerment of new leaders, it is about the empowerment of everyone.” Thanks to the global village, that everyone includes you and me.

Top photo by Rosaura Ochoa