I recently spoke to Andy Stanford-Clark, a Master Inventor and Distinguished Engineer at IBM. He’s been working on a number of Twitter and real-time monitoring projects, many of them at the intersection of two big trends we’ve been tracking in 2009: The Real-time Web and Internet of Things.

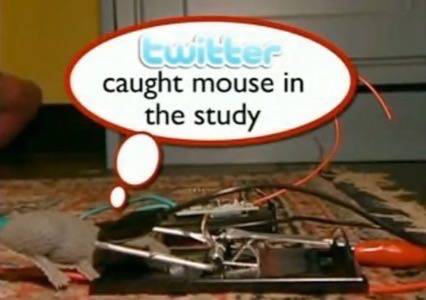

Stanford-Clark has set up various systems for real-time monitoring of the Internet of Things, many of them using Twitter (he calls the resulting tweets “tweetjects”). One example got a bit of mainstream media coverage lately: a house that uses Twitter to monitor its energy consumption.

As Rory Cellan-Jones from the BBC reported recently, Stanford-Clark has installed sensors on a number of household objects – such as electricity meters and windows. From this he can monitor lighting, heating, temperature, phone and water usage. Stanford-Clark is able to turn his fountain, lights and heaters on and off by flicking switches on a web page or from a live dashboard application on his mobile phone.

He’s also now hooked up his house sensors to a Twitter account: andy_house (it’s a private account, so requires Andy’s approval before you can follow it). Here’s a BBC tv report about the house and other similar projects involving sensors and Twitter:

As well as his own house, Stanford-Clark has also set up Twitter accounts for his local ferry and bus – for example so they can tweet their real-time locations.

What Use is a Tweeting House?

Stanford-Clark told me that as well as providing useful data about what his house is doing – for example how warm is the lounge, or has he left a door open – the system can also apply intelligence to his house. For example it can cross-reference house data against AMEE (an open platform for measuring energy consumption), in order to infer the real-time carbon footprint for his house.

These experiments are just the start of what’s possible by hooking sensors up to real-time messaging systems like Twitter. However there’s a lot of infrastructure work that needs to be done first. Stanford-Clark told me that to get at this type of data for many everyday things, governments, city councils and companies will need to instrument public things with sensors – e.g. gas pipelines, buses, trains, ferries.

The problem for most organizations, including government, is that they aren’t necessarily sure what uses there are right now for sensors. For example power companies may not see the economic value of replacing meter readers with automatic sensors. Stanford-Clark’s response is that “a lot of other apps will spring out of the woodwork,” when sensors are added and hooked into messaging software.

Stanford-Clark and IBM have identified 3 main things that are required for this trend to play out fully, conveniently summed up as “the three ‘I’s”: Instrumented, Interconnected, and Intelligent. In my next post, I’ll explore this more – plus some of IBM’s other projects in this area.