The job of stealing your personal data is now a fully-fledged industry – in some regards, one that is becoming terrifyingly legitimized. Earlier this month, security experts with Verizon gave reporters at the RSA Conference an advance look at detailed forensics data, compiled with the assistance of the world’s law enforcement agencies including the U.S. Secret Service. That data indicated that industrialized data center incursion has become mechanized, is happening regularly, and has the goal of compiling a more comprehensive “big database” about your personal transactions than Facebook or Citicorp ever dreamed.

“Most of these automated attacks are almost exclusively on small businesses,” says Chris Porter, Verizon’s senior security analyst and co-author of its annual Data Breach Investigations Report (DBIR), whose 2012 edition was published this morning. “There’s some franchise chains, but many times it’s mom-and-pop cafés. These restaurants, retail stores, are really focused on building their business. They want to make sure when a customer comes in, they can charge him. And they’re probably less concerned about data protection.”

This year’s DBIR compiled forensic information on 855 confirmed high-level data center incursions worldwide during 2011 – data that digs very deeply into how much was lost, how it was taken, and who’s responsible. Its conclusions are, to understate things, overwhelming: Of 174,083,317 total compromised data records compiled from the 855 cases Verizon studied, 173,874,419 were acquired by way of external threat agents – some form of incursion on the part of people or devices outside the company firewall. (Just in case you’re working out a comparison in your mind, the U.S. population for July 2011 as estimated by the Census Bureau is 311,591,917.)

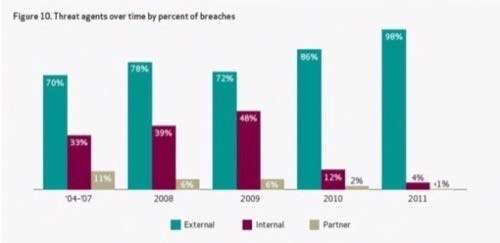

As this graph amplifies all too clearly, the ratio of outsider threats to insider threats has morphed to seemingly fantastic proportions. Over 98% of the threat agents used to acquire data originate from outside the organization – meaning, not from an employee with motive or intent to steal data or harm the firm.

“External agents have exploded, and in particular, there’s a specific type of attack we saw last year that’s even intensified this year: this industrialized, highly automated attack that organized crime directs towards small businesses, essentially,” said Porter. But then he corrected himself a bit: “It’s not that they direct them towards small businesses; it’s that small businesses are easily victimized by this type of attack. They scan the Internet looking for remote access services, remote desktops, PC Anywhere, those sorts of things; and they try to gain access with some default passwords or easily guessed credentials. Once they gain access, [they deploy] the tool that they’ve scripted and automated for the installation of malware. Most of the time, this malware is pre-configured as a keylogger. This keylogger automatically installs, begins collecting credit card data or keystroke information, and then is already pre-configured to send this data outbound.”

The Radar Scan Tells the Entire Story

To give you the clearest picture yet of the relative intensity of this mind-bogglingly simple threat, the DBIR team compiled what they call the Verizon Enterprise Risk and Incident Sharing (VERIS) framework. It’s a heat map that breaks down threat events into 315 distinct categories, charted in terms of classes of causes versus the targets of those threats.

Viewed in this context, the world of data incursion looks almost monotonous. Though the use of malware to attack servers and end-user devices (including PCs plus, more often in recent months, tablets and smartphones) is still enormously high (in the far upper left corner), simple hacking – as simple as guessing the password, like “password,” and being correct – dominates the only two red zones in the entire chart.

What happened? Three years ago when Microsoft relaxed Windows Vista’s restrictions on User Access Control for Windows 7, a minority of naysayers warned that making users too comfortable about their security settings – specifically, by reducing the reminders – might lead to them overlooking potential areas of almost certain breach. As Chris Porter tells ReadWriteWeb, those naysayers’ worst fears may have come true: Business users – particularly smaller businesses without the IT staff looking over their shoulders – are turning their firewalls off cold.

“Many times when we do these investigations, especially with the Secret Service, it’s that they don’t have a firewall in place,” remarks Porter. “Or if they do have a firewall, they’ll have an ACL [Access Control List] open to allow remote access of their point-of-sale systems, but they don’t tie that ACL down to a specific network.”

SMBs are outsourcing their information services, and usually when data is moved to cloud-based services, the protection level for that data goes up. Ironically, as Porter tells us, point-of-sale (POS) systems by their nature are not outsourced to cloud providers, but rather to more traditional software providers who install out-of-the-box solutions on-premise. Because these solutions are tied to the company network, and because the business owner just naturally assumes these folks are trustworthy (and they probably are), he gives them access to a protected account, perhaps by leaving them a password and sometimes by creating an account with no password at all. And because the solutions include software that utilizes system resources – the level that typically requires administrator privileges – the business owner chooses to elevate these solutions’ privileges through their ACL lists.

Once the password becomes “in play,” it’s a jump ball for almost anyone who wants it. Getting a hold of it can be as simple as placing a telephone call pretending to be the software provider, saying you misplaced the password, and asking for it. The little orange cell on the bottom row of the VERIS radar represents a growing cell of success for getting the password by asking for it. Although it’s only an orange cell today, keep in mind that this simple method may be, according to Verizon’s data, as effective today as a botnet-driven keylogger just two years ago.

Epidemic Proportions: The Good News

Although “hacktivism” – essentially digital terrorism, usually for populist causes – is perceived as being on the rise, and Verizon does take note of it, there’s a possibility (perhaps a likelihood) that the stage acts performed by groups such as “Anonymous” are essentially theatrical tricks to divert or manipulate the public’s attention. Even global news sources have built up these groups to be noble, humble servants working for the public good. But the targets shown on the VERIS heat map clearly indicate that, even if you don’t know who “Anonymous” actually is, there’s a much better chance one of these groups knows exactly who you are, along with your Visa number.

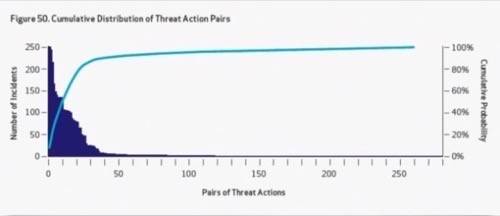

This may be why scripts, bots, and other non-social means for obtaining access remains statistically more effective than direct, personal contact – although even these automated means remain astoundingly simple. This less self-explanatory graph toward the end of Verizon’s DBIR report tells the story of how many steps it takes for a threat agent to obtain access to confidential data – in 29% of the cases Verizon studied, just one. “Essentially, the top 80% of attacks are just different combinations of eight threat actions,” says Porter.

Here’s where the dark tunnel begins to reveal a bright light: In the study of how diseases spread and how epidemics can be combatted, epidemiologists have noted that once a disease does reach epidemic proportions, the different ways the disease spread narrow down to a more limited number of methods – very effective ones, and perhaps harder to contain, but certainly easier to understand. This may be what has already happened with the rise of external exploits. So the solution to this epidemic may frankly be as simple as its cause.

“This gives us some useful ammo for controlled implementation mechanisms,” Porter tells RWW. “Maybe we can focus our efforts on stopping these eight things, and that will fix 80% of the problems we might have.”

Porter notes that point-of-sale systems, especially with their credit card-swiping devices, remain local. Thus any long-term fixes for the security holes exemplified in the VERIS map must contain local components – they can’t all be in the cloud. “Change passwords to something other than what they are right now – something not easily guessable. And put an ACL and firewall in place to protect that remote access service. Based on all these cases we’ve done over the last several years, these very simple two steps can eliminate a lot of these threats.”