For all their rhetoric and idealism about changing the world, consumer-facing technologies have largely failed at least one major set of users: people with disabilities, a segment that represents roughly 1 in 5 people in the U.S.

As the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disability Act (ADA) approaches, a new group has formed to champion the cause of development for accessibility. Several educators and tech companies have joined forces in an effort dubbed Teaching Accessibility.

According to its website, the group aims to address the “lack of awareness and understanding of basic accessibility issues, concepts and best practices.” Key participants include Carnegie Mellon and Stanford, as well as Adobe, AT&T, Dropbox, Facebook, Intuit, LinkedIn, Microsoft and Yahoo.

Of course, some of these companies may have some self-serving interest in pursuing this initiative—to boost their image, prepare for the possible expansion of ADA legislation to online services, or another reason. But that doesn’t negate the need to make accessibility a bigger priority. Not only have recent advances made this much more viable, but it’s long overdue.

Who’s Being Left Out? A Lot Of People

The Teaching Accessibility website acknowledges that technology’s support for people with disabilities has improved, but it hasn’t yet become a fundamental priority. “While there has been progress in a variety of applications, standards and regulations,” the site reads, “accessibility is still not systemic in the development of new and emerging technologies.”

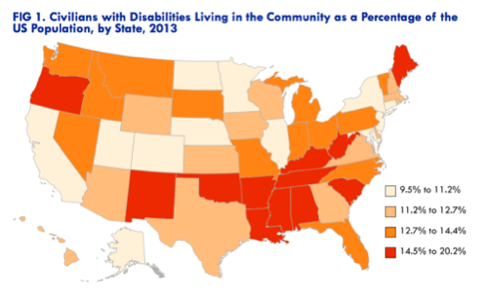

It’s somewhat mind-boggling that now, in 2015, serving users with a variety of needs isn’t part of the tech industry’s DNA. Then again, when you look at where people with disabilities tend to live in the U.S., maybe it’s not that surprising after all.

According to the 2014 Disability Statistics Annual Report [.PDF] put out by University of New Hampshire’s Institute on Disability, comparatively few tend to reside in California, the home of Silicon Valley and Los Angeles, or New York, among a hand-full of other states.

Teaching Accessibility, by its very name, seeks to educate—starting with students. The group essentially wants to reach tomorrow’s tech makers early, to cultivate a new type of mindset that’s bred from the ground up to consider a diversity of needs. It also wants to compile expertise and tools, and create standards so that any company or startup can support accessibility development.

It’s a laudable goal. And it even makes some business sense.

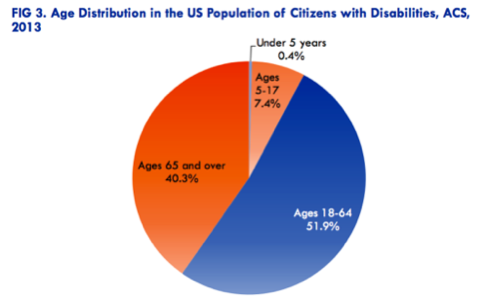

Tech companies, particularly those obsessed with the youth market, may not care that approximately 40% of Americans with disabilities are of retirement age. But naturally, that leaves roughly 60% skewing younger—from small children to teenagers to older adults in the workforce.

That’s just in the U.S. According to the United Nations, an estimated 1 billion people, or roughly 15 percent of the world’s population, live with disabilities. That’s a massive chunk of users who are at least being underserved—though perhaps not ignored entirely.

At least not by everyone.

“Accessibility Rights Are Human Rights”

On Friday, Apple CEO Tim Cook didn’t mince words when he took to Twitter to tell people exactly how he felt about serving people with disabilities.

Accessibility rights are human rights. Celebrating 25yrs of the ADA, we’re humbled to improve lives with our products. #ADA25

— Tim Cook (@tim_cook) July 24, 2015

It’s a strong, decisive statement, particularly from a tech executive. Uber CEO Travis Kalanick certainly couldn’t make it. But Cook can. Apple has a good track record of offering accessibility features in its iPhones and improving them over time.

At its latest Worldwide Developers Conference, the company emphasized its Accessibility APIs. The tools allow app makers to use the iPhone, iPad and Apple Watch’s accessibility features in their apps.

Apple offers voice over, “speak screen,” dictation, zoom and Braille display support, and on the Apple Watch, the “digital crown” (or scroll wheel) offers a tactile way of zooming in on text. Google also offers developer tools for accessibility features in Android.

But the omission of these companies in Teaching Accessibility’s line-up could make for a rather large hole. Making standards universal takes a coordinated effort. Without such tech giants in the mix, adoption for whatever standards the group comes up with could become a struggle.

That would be a shame, because advances in human-to-computer interfaces could make this an ideal time to make technology more inclusive.

Technology’s Maturing—But Are Its Makers?

Facial identification, eye or fingerprint scanning, gestures, voice interactions and other technologies have started to mature, and some have become genuinely helpful. New uses for features we’ve long taken for granted, like haptics (or vibration feedback) and geo-location, allow us to reexamine how we use our technologies.

One example: Consider a smart home that knows when its user approaches and unlocks the doors, turns on the lights and resets the thermostat automatically, or allows the owner to control them by voice. That’s a convenience for just about anyone, but for a user who can’t walk or can’t see, that could be a godsend.

The tech sector loves to pat itself on the back and buzz about those kinds of scenarios. But for the general public, they still seem like a far-off future. Right now, there are present challenges to deal with—like rideshare services that reject seeing-eye dogs, and other services or websites that disregard visitors with disabilities.

In other words, our tools haven’t let down people with disabilities. Those advances are maturing and their potential seems vast. What needs addressing is the human side of the equation, the attitudes and perspectives.

Creating specifications for technology is one challenge; setting priorities for humans is another. It’s not clear Teaching Accessibility can create a standard for that. But let’s hope so.

Photo by David Fulmer