Students who share certain tastes in movies and music – but not in books – are more likely to friend each other on Facebook, according to a study released in November that has been getting attention in academic circles.

The study has its limitations, according to authors Kevin Lewis, Marco Gonzalez and Jason Kaufman of the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University. But it is significant in that it demonstrates how social networks can help sociologists better understand social relationships and how they are influenced by cultural preferences, while also suggesting online friendships may not be effective in helping spread cultural tastes.

Sociologists have long known that so-called “weak ties” between acquaintances are particularly effective in helping push cultural trends. What the most recent study suggests is that online friendships like those fostered on Facebook are more about strengthening ties between people with similar interests than they are about influencing neighbors.

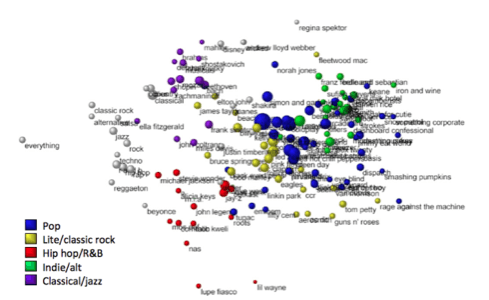

The study tracked the Facebook friendships of 1,640 students at an unidentified college over four years and found that students were more likely to friend other students with similar musical tastes, as opposed to having their musical tastes influenced by what their friends on Facebook listened to; the lone exceptions were classical and jazz music, which the researchers said were “especially ‘contagious’ due to [their] unique value as a high-status cultural signal.”

Researchers who build off of the work could soon better understand cultural diffusion, a plausible theory for explaining why fashion changes over time. Without a lab like Facebook, where participants voluntarily list their preferences, it has been difficult for researchers to substantiate how diffusion works – or whether it actually does work.

“Facebook provides users with open-ended spaces in which to list their ‘favorite’ music, movies, and books, offering an unprecedented opportunity to examine how tastes are structured as well as how they coevolve with social ties,” the study said.

The study also highlighted key ways students chose friends on Facebook, and showed that proximity was important, even in online relationships. Students were more likely, for example, to friend someone on Facebook who lived in their building or had the same major. Having just one friend in common increased the chances of students friending one another by 0.10 percent, and those odds increased for every additional shared friend.

Students also tended to self-segregate along gender, racial, regional and socioeconomic backgrounds.

What you like to listen to, of course, is far more complex than simply looking at what your friends like to listen to. The researchers didn’t know what concerts or movie nights were happening on campus, or what books were being assigned in classes, all of which could affect tastes over four years of college. They were also aware of a certain cool factor, in that some students may may have said they liked a certain type of music to fit in (and Indie rock kids, interestingly, were more likely to try to distance themselves from one another in an effort to maintain their unique street cred in musical tastes).

“In fact, students whose friends list tastes in the ‘indie/alt’ music cluster are significantly likley to discard these tastes in the future – an instance of peer influence operating in the opposite direction as predicted by prior research,” the study said.

Visualization of distribution of students’ musical preferences on Facebook. Similar tastes appear closer together in 3D space, with size being proportionate to popularity.