Does the world need another collaboration tool?

Perhaps it does, if it’s as charming and useful as Slack, the latest project of Flickr cofounder Stewart Butterfield.

A Side Project Turned Life Raft

Few people set out to build software for communication and collaboration—every notable service in this broad field, from Twitter to Yammer to Asana, seems to have sprung from a side project.

And so it was with Slack, which was built from a set of tools Butterfield’s company, Tiny Speck, developed in-house to manage communication as it built Glitch, an impressively well-designed online game. Glitch shut down last November, with Tiny Speck laying off 30 employees but retaining a core team to work on the tool it’s launching today. (Tiny Speck has 10 employees today, Butterfield told me.)

“Every startup has something like this hacked together,” says Butterfield.

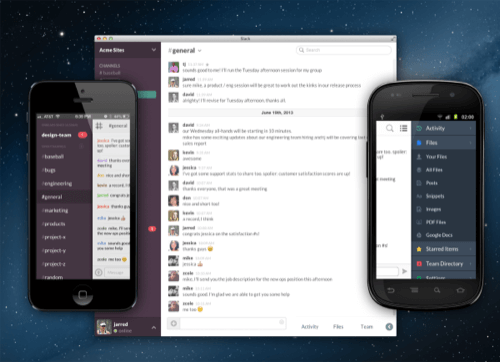

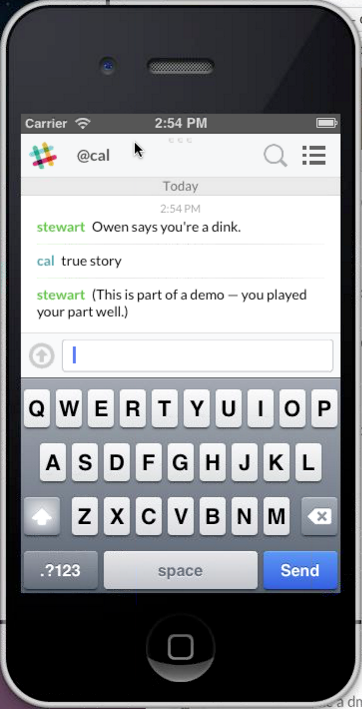

Slack includes desktop, iOS, and Android apps, as well as Web versions. It allows for private, one-on-one messaging as well as group chats organized by topic. Like many new enterprise apps, it plans to offer a basic, free version and more features in a paid version.

Hashing It Out With Coworkers

The dominant metaphor of Slack is hashtags, down to the service’s logo. But these hashtags aren’t derived from Twitter, which popularized the idea of marking topics with the “#” symbol. Rather, it goes back to Internet Relay Chat, or IRC, a communication protocol popular with coders that has long used the “#” sign to denote channels.

Tiny Speck used tools built on top of IRC to avoid use of email; Butterfield estimates that in the four-year history of the company, the internal all-employee mailing list has received about 50 emails. Slack was developed from those tools, and while it no longer uses IRC as a backend, the origins in IRC are clear.

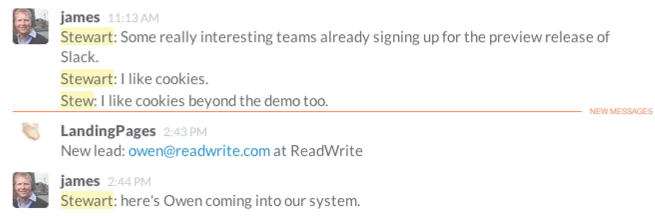

Another feature picked up from IRC: the use of bots, or automated alerting services which pop into the chat with new information. Slack uses bots to do everything from automated reminders to integrations with external services like Github, the code repository, and Trello, a project-management tool.

“This is not project management, issue management, bug tracking, or any of those things,” says Butterfield. “It’s not something we want to get into, because it’s so idiosyncratic and everyone has their own way of how work gets done. We’re just focused on communication.”

Welcoming Our New Bot Overlords

Instead, Slack includes a number of integrated services, including Google Docs, Dropbox, GitHub, and ZenDesk, and will let users build their own connections.

The intent is to cut down on automated alert emails and channel them instead into a central hub.

Crucially, Slack doesn’t just post out links to external services. It parses the data within linked documents and forms and includes it in search results.

Yammer, the collaboration service Microsoft bought last year for $1.2 billion, has some similar cross-document search features for integrated apps. But Butterfield, whose own communication tends toward liberal profanity, says that Yammer is a “piece of shit product” and likewise dismisses Chatter, a collaboration tool made by Salesforce.com.

“I don’t know anyone, at any company, who has stuck using Yammer or Chatter,” Butterfield says. “I have a theory about why. My theory is that Chatter and Yammer are both designed to be additive. They’re on top of whatever communication you already use. No one wants more stuff. No one wants more messages. It has to replace email.”

Butterfield concedes that people will continue using email to communicate externally. But he hopes to embrace and extend email, embedding messages within Slack as linkable Web pages—essentially treating it like one more app integrated into his central communication hub.

“Ten years from now, everyone will be using a system like this,” says Butterfield. “Hopefully for us, it’s Slack.”

A Workplace Conflict?

If not Slack, it may be another product born out of the collapse of Glitch.

Last year, Tiny Speck COO Kakul Srivastava, who worked with Butterfield at Flickr after Yahoo bought the photo-sharing service, left the company and started a new one, Tomfoolery, dedicated to making new, mobile-friendly enterprise apps. Its first app, Anchor, covers broadly similar territory—chatting with teams, sharing photos and links, and discussing work.

“We all had exactly the same experience and took the same lessons,” says Butterfield. “Tiny Speck was good R&D for all of us!”

He notes that Anchor and Slack are “different products.”

Besides the link in personnel, the two companies share an investor, venture-capital firm Andreessen Horowitz. Andreessen Horowitz no longer lists Tiny Speck in its portfolio, as it did until late last year. Another backer, Accel Partners, still mentions Tiny Speck as an investment.

A spokesperson for Andreessen Horowitz said that the firm didn’t view a conflict between the investments and that Tiny Speck’s removal from its website was a “mistake” the firm is fixing. Butterfield agreed that it was “an oversight.”

So hard to keep track of all these details! The oversight—if it is that—certainly points to the ongoing challenges of communication and collaboration that have yet to be solved by software.

Photo of Stewart Butterfield by Kris Krug