I hit the streets of San Francisco on an all-too-warm afternoon with camera and notebook in tow, scouting for people wearing what I thought of as the “tech uniform”—the studiedly casual California look associated with startup culture.

You know the look—company T-shirt, jeans, and the omnipresent hoodie. You’ve seen this fresh-from-the-dorm look in films like The Social Network and now in HBO’s “Silicon Valley,” the series that cunningly stereotypes the Bay Area’s tech scene. Does reality reflect the Hollywood stereotype?

I grew up in the Bay Area, so I already had an idea in my head, shaped both by pop-culture images and my own lived reality. Documenting the style, I hoped, might make me question my assumptions, as well as understand the genesis of this tech style—if indeed there was a singular style to be found.

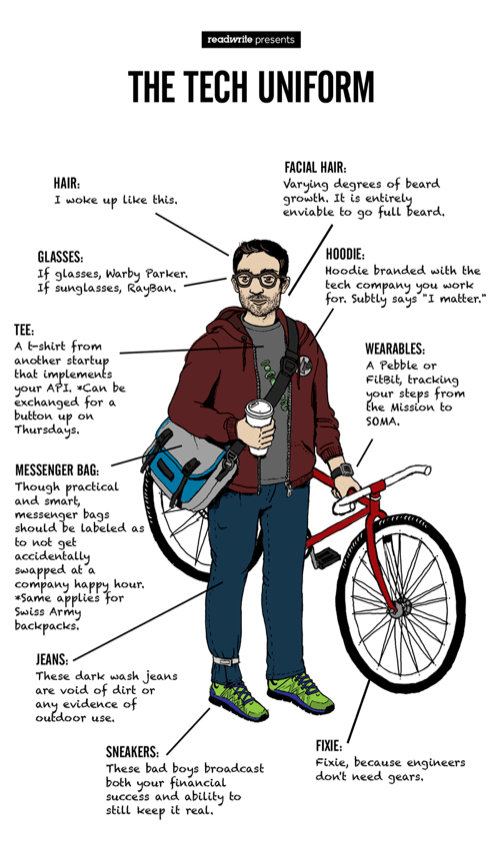

In my head, the tech uniform looked a lot like this:

The Tech Uniform: Programmer Drag?

As noted fashion thinker and ReadWrite muse RuPaul once noted, we are born naked. The rest is drag.

So even as a software developer grabs whatever’s clean in his dresser, the choices he makes reflect the culture he lives and works in. Perhaps it’s not drag as much as code—an algorithm designed around efficiency. Whatever you call it, it’s a social construction, not something you’re born with or issued when your plane lands at SFO.

The hints are all there: the branded tees and hoodies, the two-wheeled transportation, the stubbly face in transition from a goatee to a beard. Yes, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg made hoodies and Adidas flip-flops famous—or infamous. But this image isn’t based on any single person’s reality. It’s an amalgamation of many converging ideas of what startup culture looks like.

The idea of a tech uniform, we should note, is also stereotypically male—not so much gendered as male by default, created with the presumption of a male-dominated tech community. It’s the intersection of many depictions of the “tech guy”, bred both within the culture and outside of it. As author and early Facebook employee Kate Losse wrote, the myth of the “brogrammer” is more a creation of the media than a reflection of reality. Now startup employees are emulating the stereotype, wherein lies its danger.

What’s wrong with T-shirts and jeans, you might ask? On the surface, nothing. But the idea of a uniform, whether prescribed by authority or by social pressures, raises questions about who’s wearing it, and hence in the group, and who’s outside. Without a uniform, there can’t be an other to exclude.

Clearly I need a company-logo hoodie. I appear to have violated the dress code. #OpenAir #San FranciscoStyle

— Tekla Perry (@TeklaPerry) April 24, 2014

Perhaps it’s the trickle-up effect within the tech community: Young startup entrepreneurs straight out of university carry their casual academic dress into the workplace, from whiteboard sessions to board meetings. In a culture that worships young founders, the startup boss in the graphic tee and cargo shorts sets the tone for the rest of the company.

Suddenly, coworkers and investors are dressing to match the man—and so often it’s a man—at the top. Newer employees follow suit. Next thing you know, the whole company looks like it would fit in a lecture hall.

There’s also a trickle-down effect, as external representations in film and TV weigh on people’s fashion choices.

Think about Mark Zuckerberg. Now think about Jessie Eisenberg playing Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network. Then think about Andy Samberg parodying Jessie Eisenberg playing Mark Zuckerberg in the The Social Network. Suddenly, the image of the “guy who works in tech” is not only cemented in the minds of the tech community themselves, through three layers of representation and imitation.

Madame Tussauds recently revealed a waxen, shoeless Mark Zuckerberg, with a T-shirt, hoodie, jeans, and brandless MacBook. (Apple’s always so fussy about its appearance.) Along with being barefoot—not a look he’s styled for almost a decade—he’s also sitting in a chair cross-legged, which is pushing the chill factor pretty hard. This is the image that will greet tourists from all over the world, an image that will affirm and reify their idea of Silicon Valley.

It doesn’t matter that the Zuckerberg figure doesn’t look much like the nearly 30-year-old man who took the stage recently at a Facebook developer conference. The tech guy turns into a costume, and programmer drag comes into existence.

The Brogrammer Myth Becomes Reality

If brogrammers did not exist, the producers of “Silicon Valley” would have to invent them. As Losse, the early Facebook employee, noted in her essay on the myth of the brogrammer, the term, a portmanteau of “bro” and “programmer,” gained traction in the media in recent years despite starting as an inside joke, a mocking of overcompensatory masculinity among programmers who recognized that their profession was not particularly butch. A developer who rejected “typical” programmer personality traits like nerdiness and introversion in favor of the sporty gregariousness of a college jock or fraternity pledge would not have fit in well at Facebook or anywhere.

Yet as startups and technology became a sexy, mainstream phenomenon, and programming widens in its appeal, the “brogrammer” myth, picked up by the media, turns into an ideal. You can have it all, kids—startup riches and bro-sanctioned masculinity! Thus the uneasy marriage of the hoodie and the Under Armour compression T-shirt, the hipster bike pants and the designer jeans in today’s Silicon Valley.

If watching HBO’s “Silicon Valley,” which paints brogrammers as code-typing, conniving bullies in tight T-shirts with the wrong kind of Valley accent, hurts a little, it’s because it cuts too close to the truth.

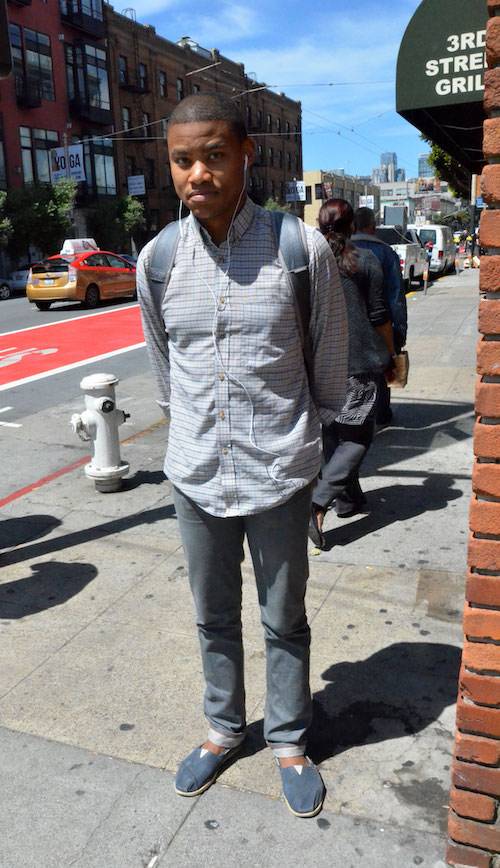

Take a stroll around San Francisco’s South of Market district, though, and you’ll see fewer fist bumps and spandex tees and more men who look like the show’s main character, Richard, in his button-up shirt and slacks.

And that’s where “Silicon Valley” inches closer to the real deal. The parody approaches parity with reality.

The Street Styles Of SoMa

I wasn’t going to find the answers watching TV shows or reading essays on the Web, so I decided to set out and document San Francisco’s real styles.

Setting forth from ReadWrite’s San Francisco headquarters—at Third and Townsend, a block away from Caltrain and in the heart of SoMa, I began my search for the real tech uniform.

Scouting people for photos in such an enclosed tech bubble is not an easy feat. Everyone has somewhere to go, lunch to get, people to meet.

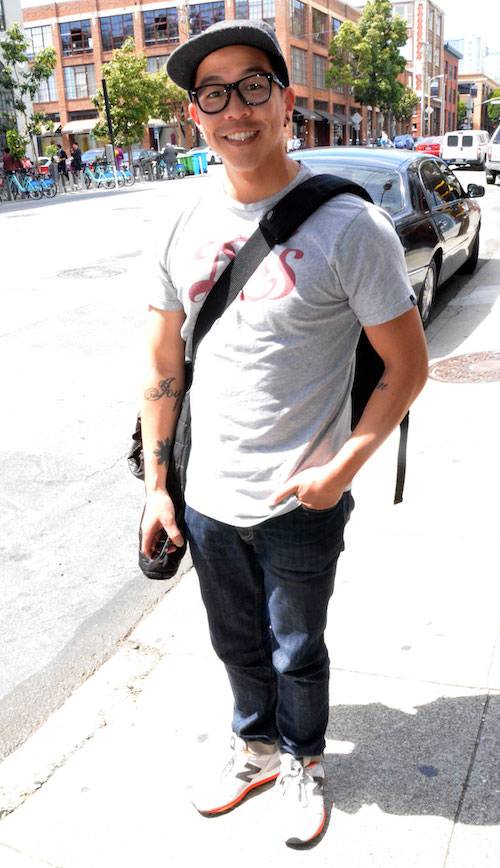

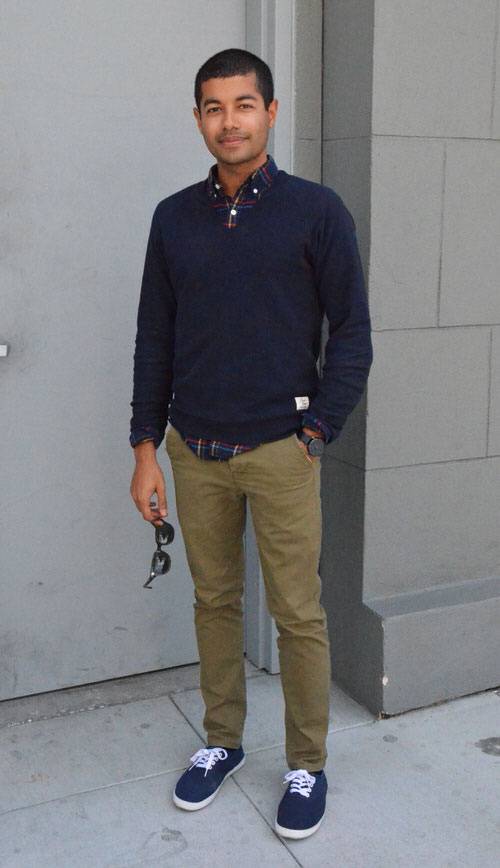

Marcus Ubungen, a film director who works out of downtown San Francisco at Goodby Silverstein, stopped to pose before hopping into an Uber—reminding us that the apps on one’s phone are as much a part of the uniform as the T-shirt on one’s body.

The trend seemed to be stylishly casual from the start. San Francisco favors comfort over fussy and complicated outfits.

Kanyi Maqubela, a venture partner at Collaborative Fund, says most of his colleagues wear limited-edition sneakers to work—an option that combines a studied ease with deliberate self-expression.

I caught up with Vijay Karunamurthy of Avos in line at Philz Coffee. Karunamurthy, who helped create Avos’s Mixbit video app, doesn’t think Silicon Valley techies pay too much attention to what other people wear. That leads individuals to feel more free to be who they are. He calls it “casual with a purpose.”

A Flock Of Coders

http://www.youtube.com/watch/gKftzAbfcGU

HBO’s “Silicon Valley” paints groups of programmers as a stereotyped flock of five—”a tall skinny white guy, short skinny Asian guy, fat guy with a ponytail, some guy with crazy facial hair, and then an East Indian guy. It’s like they trade guys until they all have the right group.”

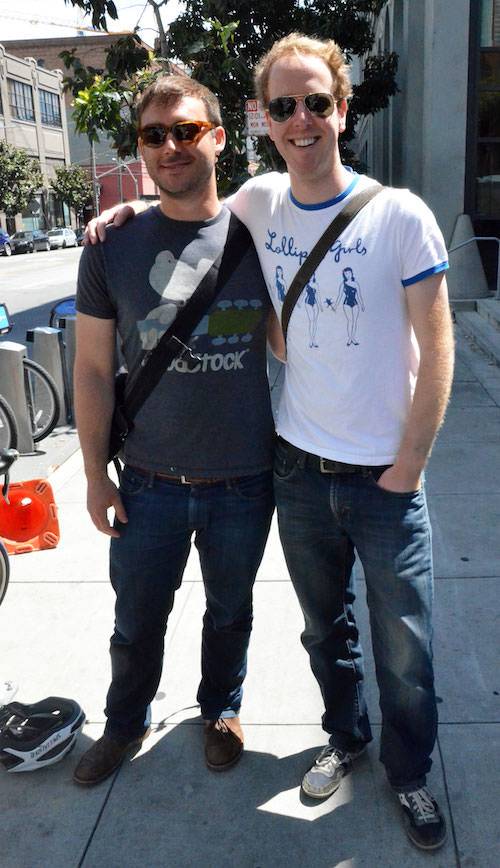

This stereotype defied discovery—I couldn’t find a group like this if I tried. But I did catch this trio emerging from GitHub’s San Francisco headquarters.

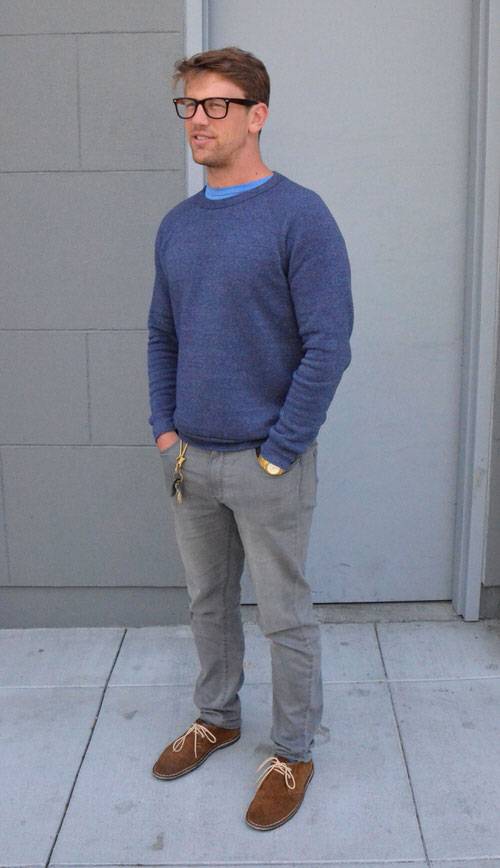

These three GitHubbers took a different stance towards tech culture’s widespread dress-for-comfort attitude.

GitHub’s David Newman describes that attitude as “intentionally casual.”

He explained that often in a tech company, newer employees will want to wear clothes marked with the company logo in order to represent the brand.

After the initial phase of decking themselves out in head-to-toe company merch, employees then go through a period of distancing from the brand.

The science of a tech company shirt is really complex. Wearing newer shirts could signify a newbie—a new hire. Non-company shirts may be worn by a longtime staffer comfortable in his role. Or these longstanding employees might also wear older company T-shirts, with outdated logos, to indicate all the years they’ve put in.

At this point in the conversation I felt as though I was being taught the etiquette of a 17th-century French court.

This idea that specific T-shirt customs within a tech company can follow certain rules and imply meaning, power, and hierarchy is a fascinating one.

It’s an example of how the everyday fashion choices of bosses and coworkers influences others in the company. Employees may not judge one another for their brand of plaid for the day, but a 2008-era GitHub shirt? That alone speaks volumes.

Logowear also makes statements about class and attitude towards wealth.

Jake Boxer, a developer at GitHub, points out that most people in tech just wear what they can get for free. That conveys a certain attitude towards material possessions that’s common in the tech culture.

Yet there remains a yearning for more: Dressed in GitHub’s signature Octocat-branded hoodie alongside his sweater-clad colleagues, Boxer tells me he regularly looks towards his more fashion-forward coworkers for style inspiration, because as he puts it, using video-game-inspired slang, “We could all level up a little bit.” Not that one has much to aspire to. It’s hard to level up when the average level is so low. Fabian Perez, a designer at GitHub who comes from the northeastern U.S., finds fashion in San Francisco’s tech culture uninspired compared to what he’s used to.

A Moving Target

I caught Lumen Sivitz, CEO of Mighty Spring, next to his bike. Besides leaving a smaller carbon footprint, this choice of transportation plays a huge part in one’s work attire. (Try biking to work in a three-piece suit.)

Sivitz says that his outfit depends on the context of his day. He’ll wear a button-up for business meetings, for example. He says none of his colleagues appear to invest too much in what he’s wearing—again, a theme that in tech, you dress for yourself.

MyProject engineer Dan Wiesenthal agrees that the tech bubble is a relatively judgement-free zone in terms of fashion, where comfort and individuality take precedent over getting in the good style graces of a colleague.

What I appreciated most was the idea that all that mattered in getting ready in the morning was their happiness for the day. Sivitz and Wiesenthal explained that “… it’s all about the right T-shirt,” paired with some brown boots or sneakers. So much meaning in such simple garb.

So maybe TV does get it right sometimes. I saw bits and pieces of my stereotypical tech-guy avatar at various points in my photo journey; a fixie bike here, some Warby Parker glasses there, and company T-shirts everywhere.

Like so many other styles of clothing, the tech uniform is a mishmash of street style and mainstream influences. Through it all, there’s a fundamental idea: Dressing not for success, but for happiness. It’s a dream we can all aspire to—if only putting on the uniform was all we had to do to live the fantasy of today’s Silicon Valley.

Photos by Madeleine Weiss for ReadWrite, Illustration by Nigel Sussman and Madeleine Weiss for ReadWrite