While much of the focus on Wikileaks addresses the legal, ethical, and security ramifications surrounding the release of secret government documents, the publication yesterday of 250,000 diplomatic cables also raises a number of questions about the existence of, as well as the security of, such a large database of classified government communications.

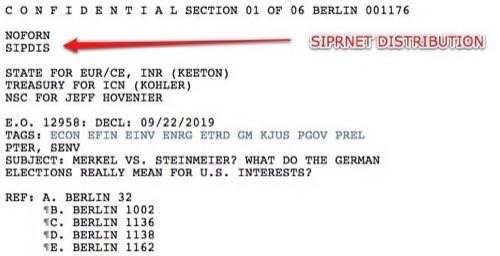

The word “SIPDIS” in the header of these cables points to their origin. SIPDIS stands for Siprnet Distribution, meaning the communications are part of the Secret Internet Protocol Router Network. Siprnet was created in 1991 and is used by the U.S. State and Defense Departments to transmit classified information, up to and including information marked “secret.” It’s a separate system from the ordinary civilian Internet, managed by the U.S. military.

Siprnet Expands After 9-11

Siprnet has grown tremendously over the last decade, as following September 11, the U.S. government has moved to link the archives across various departments and embassies, all in the hope that the intelligence they contain would no longer be siloed. Since then, more U.S. embassies have been added to Siprnet so that both military and diplomatic information can be easily shared. In 2002, only 125 embassies were on Siprnet. By 2005, there were 180. Yesterday’s Wikileaks release had data from over 270 embassies and consulates.

According to The Guardian, an internal guide for State Department staff advises them to use the “SIPDIS” header only for “reporting and other informational messages deemed appropriate for release to the US government interagency community.” There are alternative networks for more sensitive communiques. Those dispatches marked “SIPDIS” are automatically downloaded onto its embassy’s classified website, and from there they can be accessed by anyone connected to Siprnet with the appropriate security clearance.

Securing Secrets that Need to Be Shared

Those with the appropriate level of security clearance could be upwards of 3 million people, according to figures from the GAO, although a far smaller number would actually be in the position to access Siprnet. And while there are some safeguards to the system, the Guardian suggests that many of these features “were relaxed to make the system as easy to use as possible.”

This apparently made it incredibly easy for Bradley Manning, the military intelligence analyst accused of leaking this information, to retrieve the cables from Siprnet. According to The Guardian, Manning bragged that “I would come in with music on a CD-RW labelled with something like ‘Lady Gaga’ … erase the music … then write a compressed split file. No one suspected a thing … [I] listened and lip-synched to Lady Gaga’s Telephone while exfiltrating possibly the largest data spillage in American history.” He said that he “had unprecedented access to classified networks 14 hours a day 7 days a week for 8+ months”.

According to State Department spokesman PJ Crowley, “The defense department is reviewing all of their relevant procedures and taking appropriate action. In the interim, the state department has ensured that essential material reaches those who need it.” That remains the struggle for the government in this digital world – sharing while still protecting government communications.