The message from Google Executive Chairman Eric Schmidt, appearing before the Senate Antitrust Subcommittee, will be familiar to anyone who’s heard Schmidt speak before. But it began this time with a shot across the bow at a certain unnamed competitor, which he acknowleged pioneered technology and had been synonymous with the development process (as though that were past tense).

Schmidt told senators, “That company lost sight of what mattered,” and as a result had to come under Justice Dept. oversight. Without naming Microsoft, Schmidt clearly placed Google as Microsoft’s successor, not only in terms of Americans’ collective mindset, but in terms of the government scrutiny it finds itself under today. Schmidt is evidently hoping that any comparison between Google and Microsoft will automatically render Google the superior organization.

Sen. Herb Kohl (D – Wisc.), chairman of the subcommittee, opened his line of questioning by asking Schmidt, “What do you say to those who say there’s a a fundamental conflict of interest” between providing answers and providing links to sites that give answers, especially when Google is purchasing more and more companies that provide answers? Schmidt’s response was that a fundamental tenet of his company is, “How do we solve the problem the consumer has?” Perhaps Google can utilize algorithms to calculate an answer that has higher value in the consumer’s mind than simple search results can give.

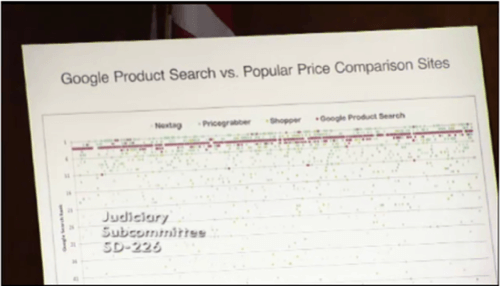

Later, Schmidt found himself squarely in the sights of ranking member Michael Lee (R – Utah), who showed a graph depicting Google’s search results in certain product searches as always within the top three. Schmidt countered by attempting to paint Sen. Lee as confused on the matter, mixing apples and oranges by mixing the results of product searches with searches for product comparisons. Google tries to take users to the product, Schmidt explained, and will respond to searches for a product by highly ranking responses pertaining to the product as opposed to product comparison sites.

“Why are you always third?” questioned Sen. Lee, evidently looking for his opportunity for an evening news sound bite. “Every. Single. Time.” Schmidt repeated his apology for Lee’s confusion, but Lee didn’t seem to hear the response. “You’re magically coming up third. Somehow you have a magnetic attraction to the number 3.”

Sen. Chuck Schumer (D – N.Y.) followed by praising Google’s position as a good corporate citizen and employer of New Yorkers, citing surveys of corporate responses to Google’s corporate policies showing 80% of respondents characterizing Google as “actually very good.” In response to Sen. Schumer’s question, what could Google do to improve its fostering of competition, Schmidt responded, “I’m always interested in creating better platforms for innovation,” citing Android as an example.

Sen. John Cornyn (R – Texas) asked Schmidt whether he believed Android constituted an example (again, not citing Microsoft) of “tying,” in which a monopoly or dominant position on one platform is used to gain advantage on another – in this case, making Android phone users utilize Google. Schmidt said no, explaining that the rules of open source software enable others to make adjustments to that software as necessary, so nothing is fixed in stone.

Thus far, senators have only been interested in Google’s potential monopoly position with respect to search rankings, often citing situations where a constituent’s placement may have been changed from high to low. Although Schmidt did bring up the topic of Android, especially in response to Sen. Schumer’s question about improvement, during the first hour of testimony, senators did not address any issues whatsoever that may be of importance to the Justice Dept. in its investigation of Google’s proposed takeover of Motorola Mobility.

Praise and scorn of Google have not fallen across party lines. While Sen. Lee, a Republican, took the opportunity to lay into Google’s ranking algorithms, Sen. Chuck Grassley (R – Iowa) warned that government should not be penalizing companies that innovate and that provide jobs.

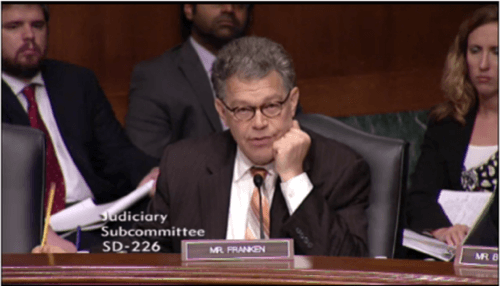

Making the most serious dent in Schmidt’s otherwise untarnished image was Sen. Al Franken (D – Minn.), who started his line of questioning by saying he’s skeptical of any company that both controls information and distribution channels, especially when it owns the companies that generate the information.

Sen. Franken cited an answer Schmidt gave earlier, saying that when users ask for a map, Google puts up a map and naturally puts it first, thus favoring a Google service over alternatives. Franken then cited a separate answer to the question, when Google responds to a search that does not require a map or other Google services, does Google provide an unbiased response, to which Schmidt had said, “I believe so.”

“If you don’t know,” growled Franken, “who does? That’s the crux of this, isn’t it? You don’t know!”

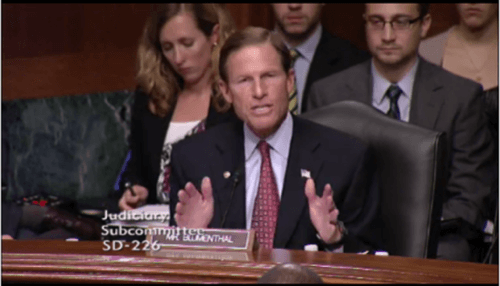

Finally during the first round of questioning, Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D – Conn.) asked rather tentatively that if Google were found guilty of violations due to its conduct, what behavior changes would it make in repentance, and what changes could it make now to pre-empt such a finding? Blumenthal tossed out a bit of raw, but spoiling, meat as bait: Would Google consider taking its own maps function off the front-and-center listing?

Schmidt responded, that would be a disservice to users because when they want a map, they deserve a map. Further, it might be unfair to Google since other competitors may not be held to the same restriction. In general, responding to Blumenthal’s request for steps Google may take to change its behavior, Schmidt said it’s already taken the most important step of all: “Making the Internet win guarantees very strong competition for all of us,” he said.