That word processor you use at the office? It was designed in the early ’80s, when the first version of Microsoft Word shipped. While revision after revision of this prehistoric technology have been released, all are modeled after a world long forgotten—a world of 8.5×11 paper, carriage returns, and ink ribbons.

The same is true for spreadsheets and databases, core productivity tools that trace their history even further back to the ’70s. As the founder of MacWeek, I saw this early wave of innovation crest—and then crash to a halt. I had almost given up hope that I would ever see true innovation in the productivity-software category again.

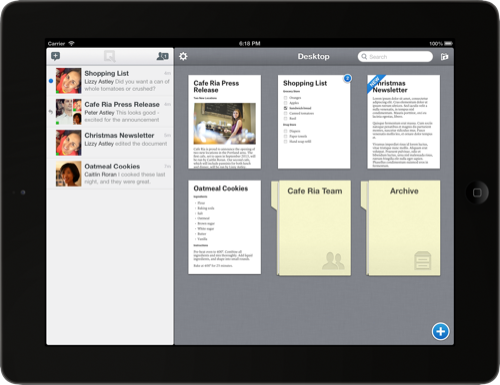

And then Quip made its debut last week.

See also: Quip Launches, Promising To Reinvent Word Processing For The Age Of The iPad

A Break From The Past

Quip is perhaps the first word processor designed specifically for the tablet era, which wasn’t even a technological fever dream when Word 1.0 was released in 1983.

What sets Quip apart is its built-in chat and collaboration. You might find that feature in Web-based text editing services, like Google Drive or Zoho, but not in stand-alone word processors.

Besides the sexy collaboration features, Quip is a stripped-down word processor. Font sizes are limited to three styles: paragraph, heading and list.

There are only three buttons: “Format,” indicated by a paragraph symbol; “Insert,” for adding external elements, such as images or tables; and “Done,” which puts the keyboard away.

The Insert button also lets you link to a person, using the well-understood @ symbol. And this is where Quip shines. It’s all about collaborative editing. If you change something, other team members swiftly receive an email.

Change is what Quip is all about, and it handles changes beautifully. When you modify something in a document, Quip will put a notification of that change in your chat stream. Each change is displayed as a sheet of torn paper. Multiple changes show up as a stack of torn sheets, which, when clicked, expand to show individual changes. (That kind of design touch, known in the trade as “skeuomorphism,” is one of the few acknowledgements of the paper-driven document world Quip has otherwise left behind.)

Quip cofounder Kevin Gibbs tells me that this change notification is called a “diff.” He says he’s particularly proud of his design for a stack of diffs.

Keeping it simple is a mandate of the mobile era, where speedy swipe operations are design mantras. It’s this sea-change shift to mobile platforms that offered Quip an opportunity to reshape the word processing landscape.

The Golden Goose Is Dead

Microsoft Word obliterated the PC market’s dominant ’80s player, WordPerfect, because it leveraged a new platform, Windows. WordPerfect’s 50% market share quickly crashed to less than 10% after Microsoft launched Word and then followed with the rest of its Office suite.

With a change in operating system came a change in market leadership. That same changing landscape exists today. As Quip cofounder Bret Taylor tells me, “We felt that this was the first time in 30 years that we could compete in this space.”

Jungle drums have certainly been beating loudly that change is needed. The first to heed the call was Google, which released a free, Web-based competitor to Office, Google Docs, in September 2007. Now called Google Drive and more focused on file-sharing, it was designed from the ground up for the internet and collaboration.

By October 2011, Google announced that 4 million businesses and 40 million people around the globe were using Google Apps, its Office-like suite of applications that includes Gmail, Google Talk, Calendar and Docs.

At the Google I/O conference in June 2012, Google noted that Gmail had 425 million users while 5 million businesses used Google Apps. (In December 2012, Google discontinued a free version of Google Apps for small businesses, which undoubtedly slowed its uptake.)

But 5 million is just a drop in the bucket compared to Microsoft Office, which is used by more than 500 million people around the world, and which contributed $24 billion to Microsoft’s $73 billion in 2012 revenues.

Microsoft can close that chapter. As Germans like to say, Die fetten Jahren sind vorbei—the fat years are over. Or in Steve Jobs-speak: The post-PC era has arrived.

There’s An App For That—Too Many Of Them

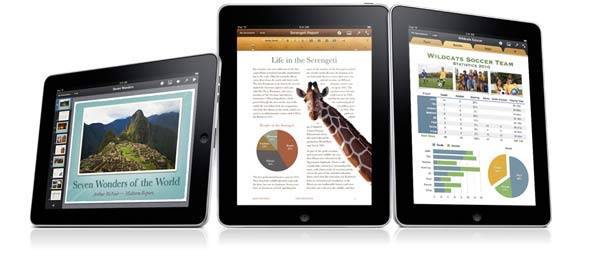

Besides Google, Quip’s biggest competitor today is Apple, which sells its Pages app for $10. Since Pages remains the most popular of the three iWork apps, and currently ranks eight in the App Store’s “Top Paid iPad Apps” list, once can only guess how many copies of Pages Apple has sold to its 155 million iPad owners.

In 2010, Business Insider analyzed the iPad app market and estimated that Apple’s iWork apps—Pages, the Numbers spreadsheet app, and the Keynote presentation app—were on track to generate about $40 million in annual sales.

Volume-wise, we know the market has quadrupled since 2010, meaning that Apple now likely sells close to $160 million in iWork apps for iOS devices—iPhones, iPads, and iPod Touch—each year. Since Keynote and Numbers linger at position 20 and 23 in the Top Paid iPad Apps list, respectively, it’s not a big stretch to estimate that Apple now generates some $80 million in sales from its Pages mobile app each year.

That’s equivalent to 8 million copies annually, or a 12% market share of all iPads sold in 2012. This formula assumes that all iOS copies were sold to iPad buyers exclusively, but keep in mind that in 2012 Apple also sold 135.8 million iPhones.

And if Apple and Google are not enough competition, an iTunes App Store search for “word processing” delivered 123 results for iPad apps. A similar search in the Google Play store delivered 48 word-processing apps, including Quip.

This may explain why Quip is free for up to five users. Organizations that need more than that pay $12 per user per month for up to 250 users.

There’s a rumor that Apple might make Pages and possibly other iWork apps free, perhaps in a bid to spur iPad sales and extra iCloud storage subscriptions. That could pose a challenge to Quip.

Quip Must Evolve Faster Than The Competition

In that way, the landscape Quip is entering resembles the early ’80s, when software makers were trying to figure out what kind of software would sell on PCs—more importantly, what kind of software would make PCs sell. There was a Cambrian explosion of diversity, one ultimately crushed by Microsoft’s Darwinian triumph.

For those who say Quip lacks the functionality of, say, Multimate in 1981, my answer is Quip is a breath of fresh air in a room that reeks of dead productivity software. And considering how quickly it was built, we can expect the team behind it to keep adding features. But the right features—not Web-based imitations of old, outdated functions.

What features will matter to users in an age when we’ve shed the legacy of desktop computers, laser printers, and sheets of paper? Are we processing words, or actually trying to communicate, to share information? That’s the question that our choice of new tools in the age of the tablet will decide.