We’d all like to get to know our neighbors and improve the places we live, in theory—but it’s frustratingly hard to connect in person, especially compared to the one-click ease of a friend request on a social network like Facebook.

This is where hyperlocal social networks come in—modern, friendly services that fit into our jumbled Twitter-Tumblr-Reddit-Instagram world.

There’s been failure after failure in this space, from Backfence in 2007 to AOL’s money-losing Patch network to NBC’s shuttered Everyblock service, which closed in February.

Finally, though, there’s a credible contender: the newly well-financed startup Nextdoor, based in San Francisco.

Nextdoor writes in its mission statement—which comes in the form of a poem—that “we believe technology is a powerful tool for making neighborhoods stronger, safer places to call home” and “we believe strong neighborhoods not only improve our property value, they improve each one of our lives.” Amen to that.

So how does it work?

The Hyperlocal Facebook

Signing up for Nextdoor was the most unique social network sign-up process I’ve encountered. Where LinkedIn is concerned with your professional identity and Facebook wants to know who your friends are, Nextdoor is chiefly concerned with your home address. That’s meant to limit each neighborhood’s network to people who really live there.

There are several ways to verify your address. You can use a credit card (you’re not charged). If you have a landline phone, Nextdoor’s automated systems can call you. A current Nextdoor user can invite you or vouch for you. Or you can have a postcard sent to your mailing address. I chose the last option.

The postcard was in keeping with the design of the site: simple and clean, and mostly white with a splash of green. It was one more statement that Nextdoor really was a local network.

Checking the real-life mailbox for a website was a novel experience, and the increased security made me feel more comfortable sharing information about my immediate vicinity. (I never got into Foursquare because of the privacy concerns.)

GigaOm writer Mathew Ingram wrote that theses barriers to entry could be the key to Nextdoor’s future success, and I’d have to agree. It may slow down signups, but it makes you feel better about your interactions with Nextdoor users.

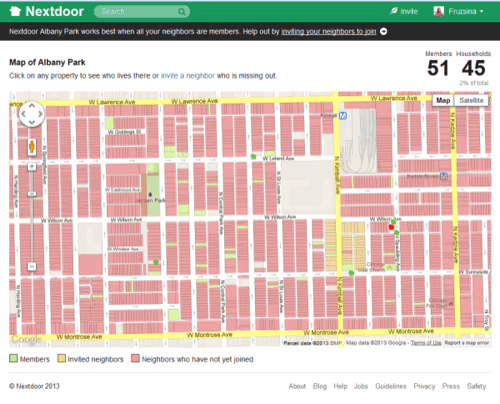

Nextdoor promises only your neighbors—those with verified addresses or proven connections to other residents—can see your posts. That should come in handy if you want to post your phone number in a message about your dog or cat being lost. Privacy concerns haven’t been completely eliminated, however: Nextdoor displays where your neighbors actually live on a map.

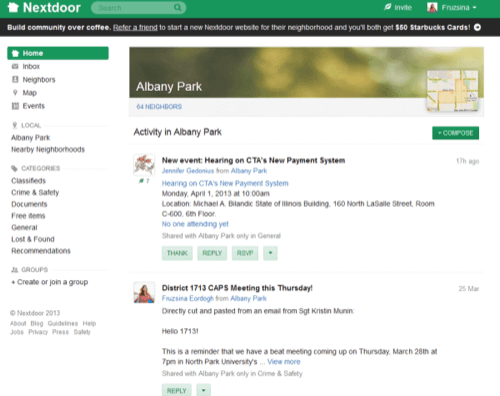

The site’s main function is to share news and information, sorted by seven categories which range from Review (for local businesses like Yelp) to Crime & Safety. Neighbors use these categories to post about yard sales, a meeting, or news affecting the neighborhood. Other site options include private messaging with your neighbors, a master list of all the neighbors who have signed up, and a calendar of events. It’s a good way to keep in touch with what is important to your neighbors.

A disclosure here: I may be more interested in local matters than the average digital citizen. I worked for various Patch sites covering the Chicago suburbs, as well as the Windy Citizen, a hyperlocal news aggregator and forum operator. I’ve also organized neighborhood cleanups and other local activities. But even if they don’t take it to my level, I feel like many people are interested in their neighborhood. They just need better tools to get involved.

Like most fledgling networks, Nextdoor’s main problem right now is the lack of active users, though my neighbors have been slowly signing up for the network as word spreads. In my Chicago neighborhood, many were former users of Everyblock, which was based in this city. But by the numbers, most people haven’t used any hyperlocal website. A 2011 Pew Internet study found most people—even those under the age of 40—still rely on TV news or newspapers for local information.

Even experienced users like me seemed daunted at having to rebuild their hyperlocal social-media experience all over again on Nextdoor. Some of the community organizations that got their feet on Everyblock—garbage cleanup groups, neighborhood beautification associations and anti-gang activists, among others—have dedicated Facebook pages.

Facebook Groups might seem like an obvious way to organize locally. Yet because it depends on existing social connections, it’s not a great way for neighbors to discover each other. Nextdoor’s address-verification system could give it an edge over broad-purpose social networks in this regard.

Creating the Perfect Hyperlocal Social Network

Everyblock’s core strength was its automated data streams. Public records like building permits and restaurant inspections were automatically indexed into a stream along with newspaper articles, blog posts and Flickr photos for each neighborhood on Everyblock. At the time, this was groundbreaking. But Everyblock took too long to add in contributions from users to capture those offline word-of-mouth conversations where a lot of local news is transmitted.

Right now, the content on Nextdoor is user-generated. But since there aren’t many users, the conversation often isn’t there. That’s discouraging for new users who sign up.

The perfect local site would weave automated feeds and social conversations to create a lively experience right off the bat. There’s a delicate balance where an urban streetscape tilts from loneliness to liveliness. Nextdoor could be on the cusp.

Photo by Ken Lund