As I stepped into the Hamm’s Building in San Francisco’s northeast Mission District Wednesday morning, I felt the presence of ghosts. I got my first big break as a reporter here in 1997, at the old Red Herring.

Asana, a business-software startup, had invited me back to my old haunts to hear about the latest version of its work-tracking software. I was curious both because we’d started using Asana at work and because, I realized, we hadn’t heard much from Asana since Facebook cofounder Dustin Moskovitz and Google and Facebook veteran Justin Rosenstein launched the company four years ago.

See also: Dropbox Is MySpace, Box Is Facebook

Asana has some 140,000 companies who use it to track projects and tasks, with the hope of eliminating back-and-forth conversations that happen in email and meetings in favor of, you know, actual work. While most use it for free, more than 10,000 companies pay per-team fees that start at $21 a month, and Asana now has “tens of millions of dollars” in annual recurring revenue, Moskovitz said.

A New, Handsomer Way To Work

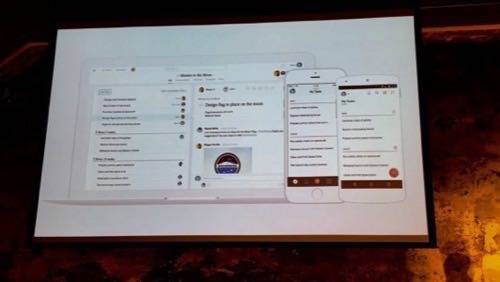

The new Asana, as the company styles it, is a significant improvement in terms of design and interface. (I’ll admit that I hissed out loud when Moskovitz and Rosenstein showed a screenshot of the older version in their presentation. I’m not proud. Well, perhaps I am, or I wouldn’t be mentioning it.)

Far more significant than the design rethink Asana went through is the shift the company is making in its approach to developers. In 2011, Rosenstein hinted at Asana’s platform ambitions.

The current API, however, is limited to pulling and pushing data in and out of Asana. This lets companies like Wufoo and Github create integrations that take activity from an online form or a software repository, respectively, and create tasks in Asana.

The Way We Work Today (And Tomorrow)

Starting next year, as Asana rolls out a new feature it’s calling “custom fields,” Asana developers will be able to modify the application itself.

The problem is that not everything you deal with at work is a task. Asana, historically, has presented itself as a task-management tool. Now, Moskovitz and Rosenstein want to expand its scope to the larger category of “work tracking,” an area of collaboration they see as coequal to file sharing, like Box and Dropbox, and messaging, the field of Slack, Convo and similar apps.

Custom fields are essentially additional data fields that can be assigned to an object in Asana. Venture-capital firms might track companies by stage and amount invested. A DNA analysis firm might track vials. A nonprofit orchestrating healthcare in a developing country might track patients. All of those require a more structured approach than a generic task.

That, in turn, opens up Asana to far more interesting possibilities for third-party developers. A healthcare systems integrator might build a generalized case-management tool for hospitals. A publishing company might create a system for tracking an article from assignment to editing and fact-checking to publication. (I did similar work, using a now-archaic-sounding tool called the Quark Publishing System, for a magazine I worked at in the prior decade.)

Asana is gearing up to work more closely with developers. In February, it hired Andrew Noonan away from Twitter to run its developer relations team.

Where things will get really interesting is if Asana starts developing versions for specific industries. That’s a strategy Box has pursued to its advantage, and would give Asana both a route into bigger businesses, with partners potentially selling Asana alongside services and other offerings.

A criticism of Asana—and a fair one, since I’ve been using it heavily in recent months—is that it feels very one-size-fits-all. Journalists at The Intercept, for example, famously despised the project-management tool when it was imposed on them by managers who weren’t familiar with the process of putting out a publication. Becoming a platform—a true platform—would let developers fill in the details and tune Asana to the precise nature of the work being done.

When I worked at the Herring in the ’90s, we didn’t have a content-management system. We barely had a system, period. I coded stories in HTML and uploaded them directly to redherring.com’s Web server. We mostly shouted at each other over the cubicles to get things done. As proud as I am of that scrappy team and the work we did, I’m sure we could have done far better with software. What a happy coincidence that—18 years on—someone is building it in the same exact spot where we reported on that era’s startups.

Update: We incorrectly referred to Asana’s new custom fields feature as “sections,” which is an existing feature in Asana’s app.