Joachim Kempin is a former top Microsoft executive and author of a recent memoir, Resolve and Fortitude: Microsoft’s ‘Secret Power Broker’ Breaks His Silence. See his earlier contributions to ReadWrite.

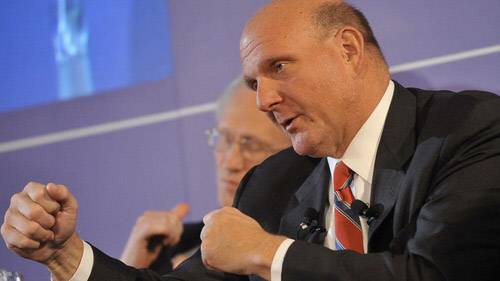

Steve Ballmer’s decision to resign as Microsoft CEO proved only one thing to me: How much he truly loves “his” company. The short answer is, not very much, because he’s getting out while the getting is good.

The “beyond Ballmer” era is going to be extraordinarily painful for Microsoft employees and its shareholders. I don’t share the optimism the investment community expressed while driving up Microsoft’s stock price as soon as the news broke. And Microsoft’s $7.2 billion acquisition of Nokia is just its latest blunder—a purchase of an irrelevant brand saddled with production and development facilities. Microsoft’s soon-to-be-former CEO is just going to make it harder for the next guy to succeed.

What Ballmer Hath Wrought

Over his decade at Microsoft’s helm, Steve has left his fingerprints all over the company. His management style has rubbed off on his underlings. Whoever takes over will face daunting challenges in implementing the changes Microsoft needs to explore growth opportunities beyond Windows and Office.

If you’re looking for one main reason Microsoft has steadily fallen behind the curve over the last decade, look to the way Ballmer’s management style changed the company once Bill Gates turned his full attention to his humanitarian work. Some describe Ballmer’s leadership style as “prescriptive” and “controlling.” Perhaps “meddling in all details” is closer to the mark. Under Ballmer, the entrepreneurial and mission-focused tenacity that made Microsoft so successful early on fell by the wayside and eventually faded away.

Not long ago, I wrote an article recommending busting up Microsoft in order to free its innovative energies. I’m convinced that this will happen—someday. The company’s pieces are worth more than the sum. But I have no hope that this will happen any time soon, much less that it will coincide with the anointment of Ballmer’s successor.

The signs are already clear that Microsoft is slipping deeper into crisis. The PC consumer market is imploding; tablets and high-end smartphones are able to serve basic information needs quite well. Microsoft has no standing in either of these categories, as you can see from its roughly 3% market share. And the company has already announced bad news last quarter when it wrote off nearly $1 billion for its unsuccessful leap into the tablet market.

Where The Growth Is—And Microsoft Isn’t

With the traditional PC market eroding and the traditional game-console business on its last legs, Microsoft needs to seek opportunities beyond its traditional niches. Embracing other platforms and rethinking consumer, social media and cloud strategies would be the most promising options.

Which is what makes Microsoft’s Nokia purchase a potentially disastrous sideshow. Back in the 1980s, Microsoft’s then-president, Jon Shirley, taught us a key lesson: Never own a manufacturing plant. Apple must have taken his advice. Steve Ballmer and Microsoft’s current board of directors continue not to take it.

Nokia’s dismal profit margins will pull Microsoft further down, and the unit is likely to be difficult to manage. (Unless you believe Nokia’s division management will be happy taking marching orders from Redmond. If so, you might want to study the Finns!) Nokia sells unprofitable devices, period. Microsoft’s shareholders ought to rebel.

Leaving behind Microsoft’s disastrous foray into devices and refocusing on software and services—meaning selling and marketing intellectual properties—remains the only successful way to go. A vastly improved version of Facebook is long overdue; somebody will do it one day and replace that odd and outdated environment. Why not Microsoft?

Innovation remains the number one task for any tech company wanting to stay ahead. A CEO therefore needs to organize so that innovation flourishes. In a CBS interview this spring, Bill Gates criticized Microsoft’s leadership for not doing so. The answer from Steve Ballmer’s team: Let’s create the notion of “One Microsoft.” I heard that slogan as early as 2000 when he took the reins. It didn’t work then and it won’t work today.

One Microsoft = One Path To Failure

See also: 9 Things Microsoft Does Right

What it meant for him, then and now: More centralization. Better expressed as, I lead and you shut up. It immediately disempowered people. Over time it sapped innovation and depleted Microsoft’s pool of creative ideas, leading to an identity crisis.

Spotting this way too late, Ballmer and the board felt it was eventually time to call for a major reorganization. Whoever did needs to look into a mirror.

In the early days when I worked at Microsoft, our identity was never in question. We followed a tactic the Prussian General Helmuth von Moltke deployed in 1866 during the battle of Königgrätz: “March separate and strike together.” (In the original German: Getrennt marschieren. Vereint schlagen.) And like von Moltke, we won. The Prussian army and the Microsofties of the early years knew their mission and acted in front of the enemy as one.

To be truly innovative, a company’s leadership needs to create a fearless and unencumbered flow of information. Successful management encourages constructive criticism and uses it as input for improvements. Further centralizing an organization, on the other hand, fosters suppression. When a leader assumes that he is the only one who knows the right way to go, it’s only a matter of time before his company loses the next big technology battle.

The Microsoft CEO Job: The Ultimate Booby Prize

I have little faith the board will choose a successor who can be the catalyst for change that Microsoft so desperately needs. It will most likely opt to follow a safe road by choosing an insider CEO for the sake of continuity. Former Wal-Mart executive and current Microsoft COO Kevin Turner immediately comes to mind, although I believe he might be the worst possible pick.

What Microsoft really needs is a dynamic leader—say, one of Google’s current lieutenants, who would show up with an open mind and a better sense for market reality. And, most important, a totally mission-oriented management style. Microsoft’s employees would welcome him or her with open arms and their chains would finally come off.

But why would anybody want that CEO job as long as Bill stays on the board? (Steve, too, most likely, given that he still owns 333 million Microsoft shares.) Both need to quit to give the newcomer a free rein and air to breath. Otherwise, failure isn’t just an option, but the most likely outcome.

Instead, though, my guess is that the board will try to have it both ways, by choosing the safest “outsider” possible. My prediction: Ballmer’s eventual successor is 55 years old and a 30 year Microsoft veteran who left the company five years ago to run a huge nonprofit organization.

You guessed it: It’s Jeff Raikes, who now runs the Gates Foundation. He is a close friend of Steve and Bill and they trust him. He is used working with both of them and will tolerate that they will look over his shoulders at times. Raikes would be the safest of safe bets—and if you ask me, his ascension has been long in the works.

Raikes will be easily tolerated by the executive team in place. Having been one of them for a long time, nobody will expect huge changes from him. He will have a tough job because he inherits a company hit by the PC crisis, which has lost a lot of its once glorious reputation. He is a nice guy and I wish him good luck.

But Microsoft can and needs to do better.

Updated at 10am PTwith observations about Microsoft’s acquisition of Nokia.