News that the use of Facebook’s reader apps was in a steady freefall got me thinking about AOL.

Or, more specifically, America Online, as the company was known back in the dot-com bubble, before it took on the AOL moniker as part of one of many image overhauls.

There was a time when AOL had more than 30 million users for its Internet services. That seems like a small number by today’s nine-digit success markers, but consider that at the time, there were only about 250 million people on the Internet. AOL shares peaked with a market capitalization of $228 billion in 2001. Today, it is a fundamentally different company focused more on content creation and distribution and was worth $2.35 billion at Monday’s close.

One of AOL’s downfalls was that it created a walled garden, trying to keep members within its content areas and making it harder for them to reach our to the broader Web. Facebook has a reverse strategy, seemingly trying to pull the entire Web within its walls, and applications like social readers are part of that strategy. They are designed solely to keep users on Facebook. If early reports are true (some are suggesting the decline is a result of changes Facebook made to its newsfeed), investors may give pause and consider the long-term prospects of the company, even as founder Mark Zuckerberg hits New York City for a highly-orchestrated road show.

History Repeating Itself?

Beyond the social reader problems, however, there are bigger-picture similarities between Facebook and AOL. Some may pan out to be real indicators of Facebook’s future, while others may just be coinicdence.

AOL’s 30 million number becomes even more impressive when you consider that as of June 2010, there were only 4.4 million still using the service that made AOL synonymous with junk mail and the mini dopamine rush first-time Internet users get when they’re told “You’ve got mail!” What was once ranked as the fourth most important invention of the Internet’s first 25 years has also been called the “service for people who don’t know any better.”

While AOL had (and has) a fundamentally different business model from Facebook, there are certain parallels that are hard to ignore as the biggest Web company to date prepares to go public.

Complaints about shifting privacy policies leveled at Facebook have the same ring of consumer outrage as questions back when about AOL’s billing practices and the busy signals that were frustrating enough to prompt millions of users to quit. Griping about difficulties in getting clear-cut answers about closing your Facebook account sounds a lot like the complaints I heard in 2000 from friends who spent hours trying to get their AOL accounts canceled after their free trials had expired.

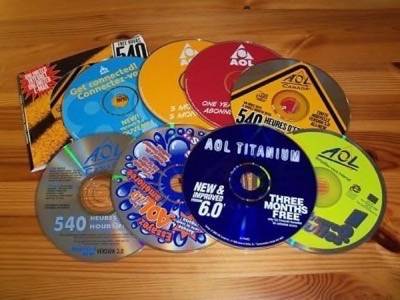

Facebook’s acknowledgement that as many as 6% of user accounts may be phony or duplicate accounts sounds a lot like AOL’s boast that its membership peaked at 34 million, not acknowledging that many of those members were using free hours the company relentlessly handed out in the form of CD-ROMs.

The Bigger They Are…

We should not, of course, be surprised. In the social networking space alone, Facebook is just the third in what may be a long line of disputable heavyweight champions, having knocked off MySpace, which knocked off Friendster.

We should be more surpised by the exceptions to the rules of the tech business – companies like Amazon.com that came of age in the dot-com bubble, survived the crash and continue to grow. But history loves a loser, and AOL is the classic case of “the bigger they are, the harder they fall.”

Writing in Forbes last month, Eric Jackson went as far to suggest that in another five or six years, Facebook (and, for good measure, he threw in Google) may be gone.

“Not bankrupt gone, but MySpace gone,” he wrote, going on to explain an economic theory known as population ecology that suggests “organizational outcomes have much more to do with industry effects than who the CEO is and the choices he or she makes.” Put another way, Zuckerberg et al were in the right place at the right time, and their successor will also be at the right place at the right time.

Big companies struggle to stay big, and that seems to be the theme of the business press as Facebook’s IPO approaches (even as the tech press, by and large, buys into the hype). The profile of business teacher and writer Clayton Christensen in this week’s issue of the New Yorker never mentions Facebook, but it’s hard not to think of the company when he uses integrated steel makers as a model for how big, established players fail to see and acknowledge new threats to their business model.

Christensen concludes that in any industry, success is difficult to sustain, if not impossible, and his book, “The Innovator’s Dilemma,” is a mainstay for CEOs in a wide range of industries (Steve Jobs was a fan, Michael Bloomberg gave copies to friends and Andy Grove, the C.E.O. of Intel, was one of the first to understand the significance of Christensen’s theories).

Zuckerberg revolutionized the way we interact with friends and “friends,” as well as the way we interact with the online world. The question for investors is, can his company revolutionize economic history?

Photo of AOL CD-ROMs courtesy of Jean Renz (Creative Commons).