The modern-day philosopher Thomas Kuhn theorized that scientific revolutions are only brought about by practitioners who are not already trained to think a certain way – or to use Kuhn’s terminology, in keeping with a given paradigm. When people train themselves to believe something, they expect their observations to match their beliefs, and thus may fail to observe something truly revolutionary. And it is observation that is the “step one” of science.

So it was with the face of Thomas Kuhn looming largely overhead that a panel of two security architects, a noted Gartner researcher, and two risk management professionals met at the RSA Conference in San Francisco last week. Two worlds collided here, and this was one of the focal points. One side represented the existing paradigm. The revolutionaries came in suits with calculators and adjustment formulas. And Gartner’s Bob Blakley literally wore a Satan suit just to make sure the fire and brimstone kept flowing.

The Balancing Act

“We teach people that risk is about science, about numbers, and about metrics. And the reality is, that only works for half of our risk. The other half of our risk is the things that we can’t predict how frequently they’re going to happen.” This from Andy Ellis, the Chief Security Officer of Akamai. No, he’s not a risk management professional by nature. He’s learned the language because, as he explained, he had to. He’s been converted to the extent, he says, that he has constructed a business continuity plan for Akamai in case of a zombie apocalypse.

“We do that because it’s an easy way to cover a whole lot of different threat scenarios. But I cannot make a prediction of what the likelihood is of that event happening. And an awful lot of the risk that we face, you can’t calculate the likelihood, we’re not part of a large population that we can do actuarial studies on. So risk management becomes more of an art than a science, and we have to discern which risk is art and which is science, and not apply the principles of one to the other.”

The traditional data center security paradigm is based around responding to threats as they occur or after they have been detected. An evolved version adds a layer of prevention, though in recent years, this layer has taken on the flavor of a handful of household maintenance tips from your afternoon local TV news. Risk management (applied properly) should be the application of principles in planning and procurement so that the impact of threats that may occur is kept within tolerable levels.

That is, when it’s applied properly. And here is where Bob Blakley enters the picture. “Risk management is not bad,” he told attendees. “It’s evil, and it’s actually the enemy of security.

“You go through this exercise every year,” said the devil incarnate. “You bring a bunch of security people into the room, and their job normally is to defend against threats.” The exercise proceeds, he explained, with these security people generating a list of threats. That list is then presented to upper managers so that they may use the principles that they consider risk management “to decide which controls they are not going to implement. In hindsight, it’s really diabolical. We get the security people to cut their own budget to participate in the exercise that builds the list of what are guaranteed to be 365-day vulnerabilities – the list of things we know are currently broken, and we’re not going to fix until we get the budget to request for next year.”

An Ounce of Prevention, As Compared to a Ton

One questioner in the audience admitted that his business employs risk managers, but says they understand some of both the art and the science, as Ellis explained it, more than they understand how to defend against threats. Confirming Blakley’s pessimistic picture, he explained how risk managers in his business calculate how much loss of business or capital it would incur as the result of a threat event, balance the more nominal losses against minimal expenses for protections and remedies, and in the act leave behind the more serious threats that they can’t afford to throw money at. Inevitably, these risk managers have the wrong executive sign off on their finalized list of expenditures, asking that executive to decide whether to a) fix the problems, or b) accept the risk. If a five-year-old running out in the middle of traffic were to run into one of these risk managers, he said, given the same type of assessment and asked to make the same decision, it’s impossible to imagine him being convinced by a table of probabilities to stay safe behind the curb.

Andy Ellis took that analogy one step further. Asking parents in the audience to confirm this observation, he said when a five-year-old runs out into the street, it’s parental instinct to run toward him and grab his arm. Hopefully this is followed by a stern explanation of the risk of running into traffic. If every time the child darted or walked or nudged his way toward the street, the parent gently nudged the child back without a word spoken, Ellis said, “you’re making a risk decision on their behalf. You’re not educating them.

“Realistically, people have a constant level of risk tolerance,” he went on. “They will tolerate a certain amount of risk, and if you take some away, they’ll go find more risk. NASCAR drivers are a great example of this. They keep doing things to make the cars safer, and they drive more and more dangerously and recklessly because they now think they’re invulnerable. So what we find is, there are fewer accidents, but the ones that happen are really big and really bad. The same things happen on our streets.”

Many executives make the mistake of believing that when the calculated reward or benefit for a project exceeds the calculated risk, then the difference between the two becomes an acceptable level of extra risk that can be tolerated for the next project. Ellis suggested that a risk decision should be met with a binary yes or no, not a calculation of probability. Security engineers should utilize those probabilities in their internal assessments, but in their end, apply their philosophies clearly and coherently. “At the end of the day, the business decision maker – the person who gets to choose to take risks, who is not INFOSEC – is making that decision,” he notes.

Acceptable Levels

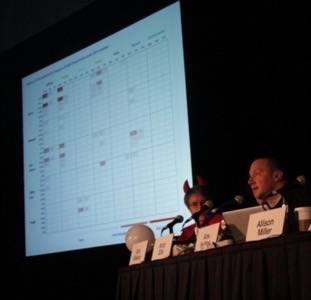

Alex Hutton is a senior analyst for risk intelligence with Verizon Business. Citing data from Verizon’s 2010 Data Breach Investigations Report, Hutton created a table of all the possible types of threats to an enterprise data center, and distributed incidents into each cell of the table by type (while Bob Blakley wiled away the time by blowing up “Anonymous” balloons). You don’t actually need to read the labels or the numbers here to make sense of the conclusions: Of all the things that risk managers say could happen in the enterprise, only a very few classes of those events are actually happening.

“It may be that attackers are particularly clever, and all that stuff. But at least we’re not forcing them to be,” said Hutton. “90% of that [table] is empty. Of all the possible things that they could do, they’re focused on 10% of them.” Hutton promised an even more lopsided shift for the 2011 table, which Verizon expects to publish soon.

Formerly a risk management professional with PayPal, Allison Miller is now Director of Security and Risk Management for social meeting destination Tagged.com. Five years ago, Tagged had a reputation as a spam producer. Now, Miller’s job is to make it feasible for the network to provide its members with tools that protect them from receiving spam. So she deals with risk management from both the user’s and the organization’s perspective.

Miller questioned Ellis’ assertion that the final decision in risk management must be a binary state. She and her team are held to a certain set of quarterly performance metrics, which are agreed upon in advance. Some of those metrics hail from the financial services realm, where she received years of experience with PayPal. “For some of the things that I’m evaluated on, there is an expected experience associated with something security related,” she told the audience, citing fraud rate as one of those measurable, agreeable levels. When you have millions of users (Tagged claims 100 million), the security state of the platform must be held to a certain tolerable metric.

“And that has been compliance, has it not? There’s an agreed-upon standard to which you’re expected to adhere,” said Miller. “And that is something that is hard to count, because compliance is either on or off. That’s an interesting challenge… If there’s a standard that’s written down, and you’re either compliant or not, that gives your management less flexibility around their risk tolerance.” What would be preferable, she added, would be “if there are other things that you could be held to that would demonstrate your performance, but within a range as opposed to something that’s on or off.”

That range can be calculated, she suggested, from an examination of user activity, and the metrics applied to it. Financial fraud, account takeovers, collusion, and spamming are among these metrics. “There’s a lot of data there, but there’s also something else that’s really important for having really high confidence and good science, which is that feedback loop – knowing whether you were right or wrong.” Right now, humans – both users and operations teams – serve that feedback, and that may actually be a problem for any business that needs more quantifiable, reliable metrics.

Harnessing the Feedback Loop

Gartner’s Bob Blakley conceded that the discussion was leading toward a possible improvement of risk management in organizations – and, speaking as the devil, he condemned it. “I love the security community’s assumption that we are a passive target, and we are hoping that the armor is thick enough. This is wonderful. Let’s quantify the probability that the enemy can hit us with a 50-caliber round from a mile away. It’s a very dispassionate statement for somebody who’s actually inside the target vehicle.”

The real feedback loop, Blakley suggested, is not the one that re-evaluates whether the right diagnoses were applied to the population of malicious agents. The true loop, he said, should be the one that signals whether what security is doing to disrupt malicious agents – the counter-offensive, if you will – is effective, neutral, or counter-productive. “As soon as we start performing experiments on live subjects… by screwing with them and watching how they react, then we will be completely indistinguishable from ‘Anonymous’ but we’ll still still think we’re on the side of the angels.”

Sometimes it’s difficult to know when Blakley is speaking in jest. Still, he blamed folks like me (he could clearly see I was media, sitting in the front row taking pictures) for agitating the situation for folks tasked with making these decisions, whether they be on-or-off or acceptable percentages. “The generation of constant, heightened fear surrounding all sorts of security instances is fashionable. It’s a free reality TV show.

“The choice that business faces is between investing money to increase revenue, or investing money to decrease losses,” Blakley argued. “To a businessperson, this is not a hard decision, and it means that the security [initiative] always takes the hit.”

“Unless a dollar of reduced loss is worth more to your profitability than a dollar of additional revenue,” countered Miller.

“The difficulty is that, of course, the security people are not in the conversation when the line-of-business executives go to the CEO and say, ‘Instead of spending one dollar to get two dollars in risk reduction, we can spend one dollar and get ten dollars.’ They’re not even in the room.”

“Is that why you invented compliance?” Miller asked the devil.