Dirk Dallas, a graphic designer currently residing in southern California, downloaded the photo-sharing and -filtering app Instagram the day it came out on October 6, 2010. He then promptly deleted it.

“It didn’t make sense because unless you follow people or have followers, what is it?” the 30-year-old university professor says of his early mindset. Flash forward two and a half years, after a friend told Dallas to give the app another try, and he has 106,000 followers under the handle @dirka.

And Instagram itself has changed, becoming part of Facebook through a billion-dollar acquisition.

For users like Dallas, Instagram is a verb, and a well-paying one. For Dallas, one recent gig involved Toyota, who paid him to participate in an Instagram-oriented photo shoot. He’s been approached numerous other times, and turned down some of the offers.

“I’ve had to walk a fine line of, ‘Wow I’m really selling out,’ or, ‘I’m pulling a fast one on my followers,’” he explains.

And Dallas is not alone. He represents a sliver of the app’s 100 million users who are not professional photographers, photojournalists, or celebrities, yet have amassed a massive following through their keen eye and commitment to the community. To put it in perspective, Instagram cofounder Mike Krieger has only 65,000 more followers than Dallas. (Celebrities attract considerably more: LeBron James has 2.5 million).

But while it sounds like a dream come true—using a smartphone app to launch an Internet-based career on the side—Dallas has battled a common enemy in many heavy Instagram users’ paths: himself.

“I used to be kind of obsessed in a negative way,” he admits. “Instagram kind of consumed me.”

Before he had over 100,000 followers and before his Instagram presence became a revenue stream, he struggled with an issue at the very core of the photo-sharing app: the way it has latched onto its users and assimilated itself into our daily lives, for better and for worse.

“Instagram kind of consumed me.”

With Facebook’s backing, Instagram is here to stay, and the effects of its pressure to scan for, snap, and constantly think about shareable moments day in and day out is central to the way our digital existences bleed into our physical experiences.

“Instagram Is Not A Photography Company”

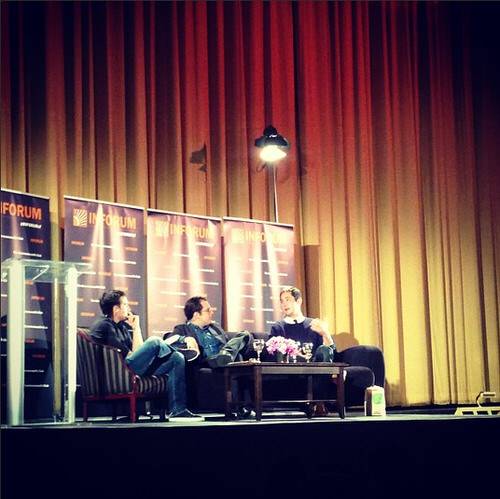

When Instagram CEO Kevin Systrom, a clean-cut towering Stanford grad, addressed a crowd at the Castro Theatre in San Francisco in May, he reiterated multiple times that the company he cofounded “is not a photography company.”

“Instagram is a communications company,” Systrom said. “It’s about communicating a moment. It just so happens that that message happens to be an image.”

His insistence of this point throughout the night’s Q&A conversation, moderated by Digg founder and Google Ventures partner Kevin Rose, bordered on the evangelical. Systrom showed an almost Steve Jobs-like marketing magic. He spoke as if the crowd needed convincing that Instagram was worth the $1 billion Facebook paid for it last April. They didn’t.

Instagram has no real competitors. Sure, there’s Hipstamatic and Flickr’s smartphone app and Twitter’s mobile photo-filter options, but none of these will ever come close to commanding Instagram’s near-synonymous identity with photo sharing in the minds of its users.

We’ll soon have physical evidence. There’s already an Instagram-linked slide projector, and an upcoming Polaroid-made instant-print camera.

As Systrom said himself that night, “Anyone can make a filter app.” What Instagram did was different. It dug into our souls, and it’s part of our daily digital ecosystem on a private and personal level comparable only to Facebook, not coincidentally.

Part of its success was in the way Instagram took the hurdles of photography out of photo sharing.

For one, you can’t make an image horizontal or vertical; all photos are square. (Apple appears to be following Instagram’s lead—a split-second preview of the next version of the iPhone operating system showed a square-photo mode.)

Within less than a minute, your photo is telegraphed to the world. With Instagram, photography became more than just easy. It became natural.

“I shared something, my photo got a bit of action, and it was awesome,” Dallas explains of the first photo he took after he re-downloaded the app a few months after deleting it on its launch day. “I got instant feedback.”

It turned out some of his friends and Twitter followers had stumbled onto his account while the app remained off his phone. While he’d temporarily abandoned Instagram, it hadn’t forgotten him—and that gave him a small following to come back to.

The feedback is the key to Instagram’s success and growth. It’s the reason communities with thousands of people spring up around hashtags in mere hours. But it’s also the source of the now-too-familiar narcissistic tendencies—that need to show everyone what you’re about to eat for lunch, for instance, and the negativity that comes with that.

Instagram is now yet another pillar of society’s continuously strained and conflicted relationship with social networks. For the photo-sharing app, the dangers lurk deeper than with Twitter or Facebook or Tumblr because with Instagram, our very experiences are our digital currency.

The devaluation of daily life to a struggle for likes and exposure and reaffirmation can force us to reconsider and reflect upon the reasons we love Instagram so much—or why, love it or hate it, we can’t quit it.

The Conflicted Relationship With Sharing

After a few months of near-constant use, Dallas decided to take a break from Instagram.

“I actually stepped back for about four months,” he says. The app ended up taking away from Dallas’s own experience of the very moments his followers were so keen to like.“Right off the bat, it made me very aware of my surroundings…. I was always trying to look for something epic to share.”

Dallas’s personal conflict exposes the potentially destructive relationship we can have with an app that also helps us connect in amazing ways.

“It seems that there are a few populations that are particularly impacted by these technologies,” says Morgan G. Ames, a graduate of Stanford’s PhD progam in communication who specializes in the ways new technologies impact our everyday lives. “One would be parents of younger children who can capture and share all aspects of the minutiae of their children’s everyday lives.

“Some parents seem to feel a tremendous pressure to capture all of the ‘important’ moments of their child’s lives, which can make their lives feel more exciting and important, but can also add a great deal of stress,” she adds.

This kind of Insta-stress happens in other circumstances, too.

Take the food photo for instance. As early as August of last year, GQ’s Luke Zaleski wrote, “The best way to Instagram your food? Don’t. It’s time to go on an Insta-diet.” More recently, you have the Tumblr “Pictures Of Hipsters Taking Pictures Of Food.”

This idea that people were so consumed with sharing their every moment—something people previously said about the Facebook status and the tweet—seems magnified with Instagram. Taking a photo of your perfectly composed food suggests that you think it’s beautiful enough to share with the world—but not delicious enough to start eating immediately.

And food photos are only the tip of the iceberg. Think about every time you visit a famous landmark, ride your bike past a beautiful landscape, or notice how striking the light of the sunset looks against the clouds.

“Many photographs today are take-once and view-once (probably in the next few days), and have little value beyond that, at least currently,” Ames says. “I can imagine archaeologists sifting through our digital remains sometime in the future and these photographs serving useful functions for them, but will we ever go back and look at our meals and shopping lists and pretty sunsets? It’s hard to say.”

When Systrom explains the ideas driving Instagram’s popularity, he strikes a particularly interesting note when he says that life in the digital age is driven by staying in touch, that central desire of human nature that made us, in the pre-smartphone age, increasingly more separated from those we used to know as time goes on.

“Success to us in the future is where everyone in the world has the Instagram app in their lives,” he says.

Keeping in touch through Instagram is a fantastic solution to bridging the thousands of miles that separate us from friends and family members, but it’s also a very superficial and one-sided take on the social network. To go deeper, Ames suggest, you have to be willing to accept the fact that Instagram has cheapened the photographic image, and therefore by extension, lessened the value we get out of moments we’re so eager to share.

“It seems that photographs are now more commonly being used as a stand-in for medium-term and even short-term memories as well,” she says. “Even though the resulting photographs are cheapened, the pressure to take the photographs in the first place hasn’t necessarily lessened.”

“Success to us in the future is where everyone in the world has the Instagram app in their lives.”

Viewed through a social-network lens, if Twitter is an inside look into someone’s mind from a textual standpoint, and Facebook a view into that person’s world from a social one, then Instagram is the next frontier: the closest thing to participating in someone else’s physical experience, visually.

That’s where the pitfalls for all of us reside. Ames sums up the ambiguity of Instagram’s value when pitted against the compulsions it fosters on a personal note.

“I rarely go back and look through these photographs I’ve taken—time and attention, as always, are the bottlenecks—and I sometimes joke, even as I take photos, that it’d be better if I just put the camera away and experience the world more directly,” she says.

“Of course, I don’t.”

Image Control

When Dallas rejoined Instagram in late 2011, he felt refreshed. It was this new take on the app that let him approach it in a manner that reassured him he had the control, and 100,000 plus more followers without needing another break set that in stone.

Since then, Dallas’s life as an Instagram celebrity of sorts has pushed him far beyond what he imagined possible when, at his friend’s insistence more than two years ago, he put the app back on his iPhone home screen.

More recently, he was approached by Orchestra, the company behind iOS email app Mailbox, while it was in beta. It wanted to feature his and other Instagrammers’ photos as a reward for users who hit “inbox zero”—a state of cutting through email clutter. (That’s how ReadWrite first heard of Dallas’s work.)

When Toyota approached him recently for a special vehicle shoot, they didn’t want the photos he could take with his Canon 5D Mark III. “They wanted me to bring my iPhone,” he says with a laugh.

“I’m still looking for awesome shots to share that are interesting and maybe inspiring, but I’m trying to not let it just be about Instagram,” he says. It’s a feeling not so unfamiliar to many of us in our daily lives who find ourselves in conflict with the obtrusive nature of a smartphone and the crisp click of a shutter-mimicking tone the moment a scene strikes us.

For Dallas, it helped to tell himself, “‘Hey, I’m at this cool spot, I need to be here right now, live in the moment.’” For him, the pitfalls of the app are avoidable through this self-meditation. “So now I feel like I’m bringing Instagram with me as opposed to I’m just going somewhere to Instagram.”

Just last month, Dallas visited some visually stunning spots in Arizona and New Mexico with friends, and brought along his Canon DSLR because he was less worried about Instagram authenticity and the idea of an immediate post.

After his trip came to a close, he shared a select few shots, specifically some astounding long exposure light images, with his followers, stressing to everyone that the shots were taken with his “big-boy camera” for pure pleasure.

“I wanted to experience those in my eye, to make those memories,” he says, “and Instagram came along.”

Photo of Kevin Systrom and Mike Krieger by Nick Statt for ReadWrite; all other photos [except food photos] by Dirk Dallas