Yes, there’s an app for that. But even if there is, you definitely shouldn’t write it. Not if you’re an indie developer, anyway. (Or you enjoy poverty.)

While it’s easy to point to successful mobile apps, for small, independent app makers, these are the exceptions to the rule.

Just as the Web’s early rise wrongly made us believe in the Long Tail, the theory of success moving from a few dominant mega blockbusters to a broad universe of niche hits, mobile’s halcyon days made us believe that “there’s an app for that” would translate into a financial bonanza for mobile developers.

For some, it has. But not for most—not by a long shot.

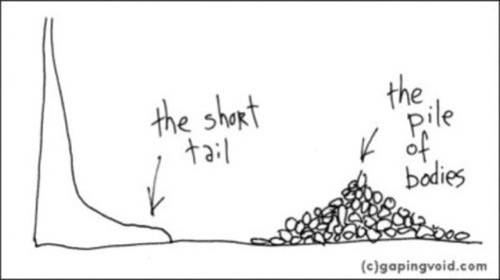

The Long Tail turned out to be short, as Hugh McLeod’s drawing insightfully argues. And today’s app stores, though open to all, is closed for (your) indie business.

That leaves budding developers, makers and builders to face a harsh reality: At one time, they might have found the best opportunity to express their ideas through app ideas and app development. Now it’s hardware, connected devices, and services that exploit and serve those innovations.

See also: Google’s Offering Smarter Tools For Smarter Apps And Homes

Ultimately, if you want to innovate, then build new products or services. If all you know how to do (or want to do) is write apps, your best bet is to go work for The Man.

Getting Noticed, Getting Paid

Not everyone agrees. For example, Pollen CEO Mark Macmillan would have us believe that the steady increase in new apps signals a “clear indication that the app economy is strong.”

Actually, for any individual developer’s own “economy,” those swelling ranks tell us the opposite.

One reason we have more apps is because it has become progressively easier to build them. Tools like Apple’s Swift programming language, Google’s latest Android Studio 1.3, and even outside services for porting to different platforms or prototyping, all aim to simplify the process of making apps.

See also: Apple’s Swift Move: How Its New Coding Language Could Shake Up iOS Development

But while development has become easier (and apparently cheaper), those streamlined processes make for more crowded app stores to fight through.

That, invariably, means less money for the indie.

Part of the problem comes down to attention. The bigger Apple’s or Google’s app stores get, the less likely it will be that anyone ever discovers your app. That’s one reason more people will grab Big Brand X’s truly awful download before they’ll sniff at yours. They know (and presumably love) Big Brand X, so it’s a natural hop to move to its mobile app.

But you? You’re almost certainly a waste of screen real estate.

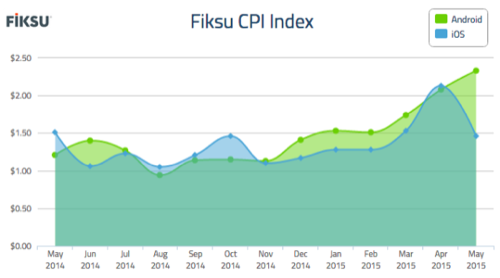

You may believe that the huddled masses would love your app, if only they could find it. Too bad you’ll probably never know. Marketing apps to new users has recently become a little less expensive, but it’s still not cheap to get someone to download an app, as Fiksu’s data shows:

Once you do get people to install your app, that’s still only half the battle.

Macmillan points to MIDiA research that indicates “many of today’s blockbuster games are not acquiring new audiences.” He thinks that should warm the heart of indies hoping to break into big-time revenue. On the contrary, that may do the opposite. The mobile app world’s best examples of success look like a desperate scramble to acquire an audience, followed by a plateau. In other words, good luck trying to keep the growth going.

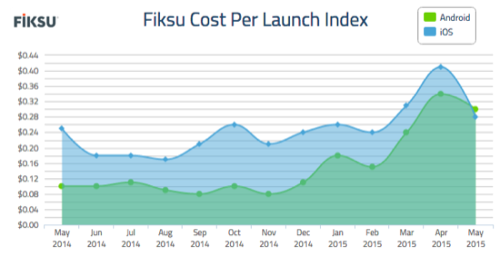

According to Fiksu, which measured costs in relation to app launches over time, the expense of keeping users engaged adds up quickly. Recent figures show they’ve risen 188% year-over-year for Android and 13% for iOS:

Overall, Brent Simmons’ lament rings true: “The iOS App Store is, to understate the case, generally unfavorable [to app developers making money]. Indies don’t have a fighting chance.”

You Could Get Lucky

Macmillan’s point of view is obviously more optimistic. He predicts an imminent future “where more app developers will have more chances to make more money.” To support this he cites data that shows “the number of publishers making between $1,000 and $5,000 monthly has increased 12 percent to reach 6,300 publishers in April 2015, up from 5,600 in September 2014.”

That’s great news. Sort of.

For one thing, it overlooks the reality that all apps are not created equal when it comes to getting paid. On average, roughly 70% of the time we spend in apps is restricted to our three most frequently used apps, according to Flurry data.

Your odds of becoming one of those three are very, very small.

That is, unless you’re developing a game (32% of time spent in apps), Facebook (17%), or social messaging (10%). And games? Well, if you look at the top grossing apps/games, they tend to not be written by indie developers. Supercell, King.com, and Machine Zone all have multi-billion dollar valuations.

Maybe you don’t need to make a mint. But you do need to pay your rent. Good luck with that. According to Flurry, roughly 52% of apps lose half of their peak users within three months. And games, despite owning a large chunk of our time, struggle mightily to retain users: 50% of gaming apps lose 50% of their peak monthly active users within two months.

But maybe you’re not a game, or Facebook, or a messaging app like Whatsapp. That leaves 41% of the market to fight over. But subtract Twitter (2%), utilities (8%) and YouTube (4%), and that segment dwindles. What you wind up with is just a quarter of a user’s potential app time, extending across an average of 26.8 apps we use on a monthly basis, according to Nielsen.

That doesn’t mean it’s impossible to make it as an indie developer. But the odds of success certainly aren’t in your favor.

Big Is Different

The same is not true for big brands. Part of the reason is because most aren’t in the app business, per se. Mobile apps are a means to an end, and that end is not normally the lavish retirement of their developers.

Larger enterprises tend to see mobile as part of a larger multi-channel strategy. Even when mobile drives considerable revenue—one U.S. retailer recently told me that they expect to do $2 billion this year through their mobile website and app—it’s still just one source of revenue among several.

So what’s an indie developer to do? Switch gears. Maybe even literally.

ReadWrite Editor-In-Chief Owen Thomas recently observed that “what was largely a software phenomenon has turned into physical hardware.” Increasingly, innovation has been leaping off flat screens into three-dimensional products you can touch and hold. “The mobile and social revolutions have largely run their course; while people will still reap the rewards of those innovations, the opportunities are fewer and less interesting,” he wrote.

If hardware’s not your calling, Simmons offers another alternative: Go work for “The Man”:

You the indie developer could become the next Flexibits. Could. But almost certainly not. Okay—not. What’s more likely is that you’ll find yourself working on a Mobile Experience for a Big National Brand(tm) and doing the apps you want to write in your spare time. If there’s a way out of despair, it’s in changing our expectations.

VisionMobile agrees. If there’s one thing its data has consistently shown for years, it’s this: Enterprise app developers may not have more fun, but they make a lot more money than consumer-facing, independent developers.

The time has come to stop thinking up “apps for that,” and perhaps start building “apps for them“—that is, for the big brands that can actually afford a more sophisticated mobile strategy.

Lead photo by Jason Howie