An unlikely place to look for the latest trend for the Internet of Things is inside the sewers of the City of South Bend, Indiana. For the past six years, South Bend’s city managers have been working with a group of consultants from IBM, nearby Notre Dame University and others to instrument the city’s sewers as a means of delivering better service and saving hundreds of millions of dollars in capital improvements.

South Bend was facing more than $600,000 in potential government Superfund fines to bring its system up to par and had also experienced a series of regular overflows. Rather than build expensive new capacity, the city embarked several years ago on a project to do a better job monitoring its sewer conditions in both dry and wet weather. To do this, it needed to invent cheaper and better sensor technology that it could literally insert into the pipes and connect to a real-time monitoring system.

“We needed sensors which were more economical and higher-definition than our traditional systems,” said Gary Gilot, a member of South Bend’s Board of Public Works (BPW). The city eventually built a monitoring system of more than 100 sensors, conceptualized by city engineers and developed in Notre Dame’s engineering school, and deployed them throughout South Bend’s 500 miles of sewers.

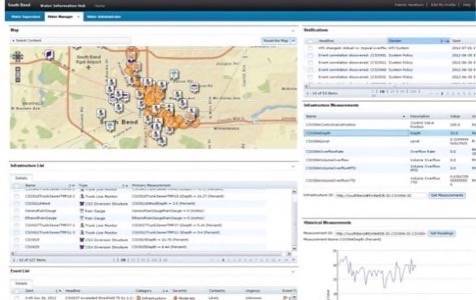

Like many sewer districts, the South Bend BPW had been using 50-year-old mechanical valve technology to operate the system and direct water flows through the city’s pipes. The new technology (pictured above) enables the city managers understand the demands and actual real-time usage and flows. “At a glance, we can see in real time what is happening across our entire system,” Gilot said. “We are also able to examine how our system behaved in previous years when we had an inch of rain, so we can be better prepared now.”

Spend $6 Million, Save $120 Million

The annual sewer operating budget is about $30 million; South Bend invested about $6 million in the monitoring project and estimates it has saved $120 million in infrastructure improvements. Not a bad return on investment! The city is now able to do a better job predicting and responding to basement backups in low-lying areas; using its new residential basement “heat map,” South Bend can now direct utility cleaning crews to areas where they are most likely to be needed. And through the new monitoring capabilities, the city has also been able to reduce the flow of water through its treatment plants by up to 10 million gallons of water per day.

The city didn’t just decide to instrument its sewers overnight. “We had to convince the mayor, and it took some time,” Gilot said. “We first set up our sensors in the lab and then next tried in the lakes near Notre Dame.” When these demonstration projects were successful, the sewer department set up a trial at one place in the system that had some overflow problems.

The trials allowed South Bend to work out problems before a full deployment. For instance, placing the sensors inside pipes buried in the ground meant that it was hard to get radio signals out of the sewers. “We had to use our manhole covers as transmitters so we could get the sensor data out of our pipes,” Gliot said. The city also needed to work on parsing all of the sensor data and creating visualizations to make the information useful and actionable.

The South Bend project represents the next stage of the Internet of Things – individual sewer pipe valves that can be tracked and controlled, with the added layer of data visualization to make it manageable and actionable. The city government is now looking beyond its sewers and seeing what else it can instrument to save money and deliver better services to its residents. That has certainly caught the eye of many other sewer and water districts facing similar circumstances.