On the Internet, every site you visit is recorded. There are tools to help block this act, but what does it really mean to be tracked on the Web? And what types of information do companies have about you?

Tools by Disconnect literally “disconnect” you from Facebook, Google and Twitter so that these major sites don’t keep track of your browsing. A new tool called Collusion for Chrome shows users all the websites that secretly track you as you browse the Web. How do these tools work, and what are the advantages to using them? There is a hope that one day, our Web life will be private again.

“If consumers express increased concern about this kind of tracking,” says ESET security evangelist Stephen Cobb, “then we might see the people who do it moderate that behavior. One view of this is that the market will determine whether people keep getting tracked.”

Something like this has probably happened to you: You read about back surgery on some website, and then every page you go to has an ad for a back surgery clinic in Florida. This is an example of cross-site tracking technology.

It is exactly this type of behavior that Disconnect’s tools try to combat, or at least slow down by inspecting the outgoing requests from the browser. These behave differently from Firefox’s Do Not Track and Google’s Incognito browsing.

“Even if something like Do-Not-Track gets wide industry adoption, there’s a small chance that those 7,000 third parties that we discussed in our presentation at DefCon will actually respect the Do-Not-Track header,” says Brian Kennish, founder of Disconnect.

Google Incognito browsing is not as hidden as it seems. While it’s a useful way to clear out cookies every session, what it really does is wipe out all cookies from a specific browsing session after you shut it down. It is best for browsing on a public machine.

How Disconnect Works

“The extensions inspect the outgoing requests from the browser, and they all have at least a blacklist, and they generally have a whitelist as well,” says Disconnect Founder Brian Kennish. “For any given request, they’ll check the request against their blacklist and see if it’s going to that domain, and if so it will stop the requests.”

Some extensions operate only on cookies, which means they will prevent cookies from people who are on the blacklist. That is not how Disconnect tools operate.

“Our extensions operate at the request level, because cookies are only one way in which ads, analytics and ad companies can do the tracking,” Kennish says. “Cookies are only one way users can be uniquely identified. There are other ways, like IP address, LSOs (flash cookies) and browser fingerprinting, to name a few.”

Disconnect offers tools that stop Facebook, Google and Twitter from tracking your browsing activities.

“Organizations that are getting a significant chunk of users’ browsing history, like Google, Facebook, Yahoo and Twitter, can get upwards of 5% of a users’ browsing history, which becomes a significant number. If you open up history in your browser and select 30% of sites and email them to Google, that’s what it’s like,” Kennish says.

Yet block out too many sites, and you walk a fine line between protection and convenience – blocking too much just makes the browsing experience feel completely inconvenient.

Collusion for Google Chrome Shows How Websites Track You

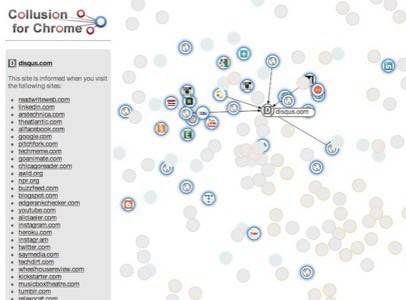

Six weeks ago, Mozilla launched a Collusion extension that tracks which websites are tracking you. Disconnect just did the same thing for Chrome, making it possible to see how widely sites you visit are disseminating your data. It gives you a peek into the secret world of invisible tracking on the Web.

“We’re just scratching the surface of what can be done visualization-wise,” Kennish says. “Our two priorities are to educate and help users understand what is happening with their data, and to empower users to understand how their data is used or not.”

The second step is the main focus of Collusion, which scans sites that set cookies and additional signals.

“What consumers have not fully realized yet is that much of their activity is in a database, somewhere,” Cobb says. “And the extent to which companies are trying to connect those databases so they have a broader look at your behavior.”

Lead image courtesy of Shutterstock.