In the six years since Jeff Howe coined the term ‘crowdsourcing’ in Wired Magazine, the phenomenon has grown into several distinct, maturing industries that give businesses and workers almost limitless flexibility. But crowdsourcing also significantly changes the relationships betweeen employers and workers – and not necessarily for the better.

The 3 Types of Crowdsourcing

Howe’s definition of crowdsourcing (taken from a trailer for his book) is pretty straightforward, if a little broad:

Crowdsourcing is when a company takes a job that was once performed by employees and outsources it in the form of an open call to a large, undefined group of people, generally using the Internet.

Depending on how you interpret “job,” that definition could include crowd-based funding, like Kickstarter, crowd-based voting, and other community-driven decisions, but most commonly the term applies to marketplaces for soliciting work products.

Typically, businesses offer up a request for a block of work, like a logo, software coding, marketing copy, a website or a list of voicemail transcriptions – and the crowd answers the call. Those are the basics. Every crowdsourcing marketplace has its own rules and specialty, but generally, they break down into three categories:

1. Contests

2. Open Markets

3. Microwork

Each type of crowdsourcing requires a different approach to get the most value for the money and effort you put in – and to avoid the very real opportunity to anger your existing workers and contractors while exploiting crowdsourced contributors (assuming you care about that):

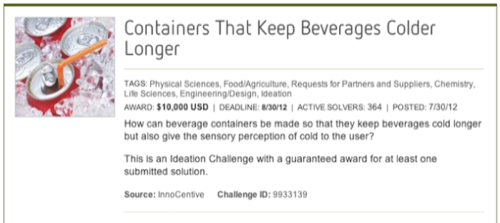

1. Contests: Contest marketplaces solicit responses as an open call and generally choose just one as a winner. The client purchases the winner’s work product with the award, and the losing entrants retain the rights to their work product. Contest specialties range in scope from small graphic design projects (Crowdspring) to substantial scientific quandries with awards in the tens of thousands of dollars (Innocentive).

Very few people have a problem with the top end of the contest crowdwourcing market, which tends to add unique value with sites like IdeaConnection and Xprize . Innocentive, for example, rewards creative thinking, requires domain expertise and helps identify talent that might otherwise remain buried. Plus, Innocentive participants are trying to solve important problems, not just grind out grunt work to pleases the corporate overlords. If you want to offer a million dollars to the first person who can cure acne, have at it. Everyone wins.

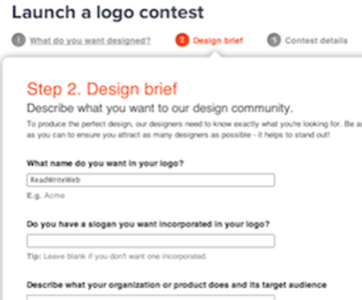

Low-end contest sites like Mycroburst are a different animal. In these situations, the majority of participants end up performing hours of work with zero compensation. A logo design project, for example, might start with 100 participants, then work through several rounds of revisions and cuts before settling on a winner, who might earn as little as $200,

For the winner, if there is one, the reward might barely justify the expense. For everyone else, it’s a total bust.

To mitigate this situation, some contest sites have created secondary marketplaces (like the 99 designs Logo Store) to help artists recoup at least some money from non-winning work. Still, contests conjure the specter of ‘spec work’, and many artists have attempted to organize boycotts of them as abusive exploitation.

So what’s the right approach? At the very least, companies need to be honest about what they can spend and what they need when they create a crowdsource contest. And they need to be realistic about what they’re likely to get – a competent if not brilliant solution to an immediate problem. If that’s all you need, a crowdsourced contest could be all you need.

In most cases, though, if you can afford to actually hire a designer or a coder, you’ll get better work, more consistency, with far less ongoing management effort.

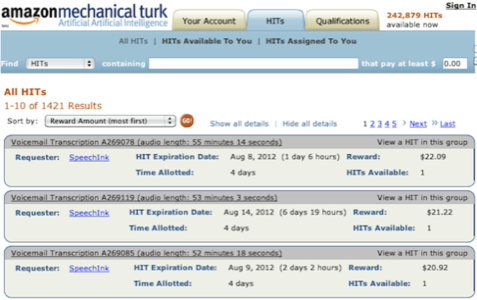

2. Open Markets: Marketplaces like oDesk, eLance, Guru, and Mechanical Turk allow employers to post nearly any job at any price, leading to a wide range of offers, from 20-minute typing assignments to complex, multi-week software development projects.

Open markets are generally free of stigma, but managing the projects can become a full-time job. Job posters often need to sift through a number of low-quality providers (or high-quality providers with the wrong domain expertise) before finding the right match. A poorly-defined job description will compound this problem, attracting too broad a range of applicants, and discouraging the real pros who don’t want to waste their time.

If you aren’t completely sure what you need, you may do better hiring a local to work through the process on-site. If you really do know what you want, be as specific as possible in your posting, and create a quick qualification process on which everyone in your office agrees.

3. Microwork: Microwork marketplaces break up large, repetitive projects into very small, discrete chunks that are managed by a highly-automated software. In most cases, the need for microwork will be driven by specific projects.

Microwork marketplaces typically focus on a specific type of work. For example, Microtask focuses on very large projects involving text and data recognition – specifically, handwritten, damaged or stylized text that computers can’t read. It has built its entire user interface and back end around increasing worker productivity for this very specific job, and the majority of its tasks take only a few seconds to complete.

Crowdsourcing task work is a delicate decision, since it pulls hours from an in-house team, needs to integrate with in-house workflows, requires a very well-definied data specification and requires a certain amount of trust in data quality.

When it works, crowdsourcing microwork can be brilliant. When it doesn’t, it’s a train wreck. Before entering into a contract for microwork, it’s criticial to nail down the specs, do your homework (and check lots of references), and give as much power as possible to the project leads so they can make the process work as efficiently as possible.