Dennis Crowley’s vision for Foursquare extends way beyond the check-in.

The cofounder and CEO of Foursquare envisions a future where our mobile devices learn our behavior and provide suggestions for events, or what to eat for dinner based on a taste profile the company has developed by observing our behavior over the years. People will spend less time on decisions and more time on experience, because our phones can make them for us.

The simple act of “checking-in,” or sharing your location data with friends on various social networks, does more than alert followers to where you are—it creates a data point that contains significant personal information about you and the businesses you patronize. Foursquare’s aim is to turn that data into new services for you—and its advertisers and partners, of course.

See also: How The Internet Will Tell You What To Eat, Where To Go And Even Who To Date

Foursquare check-ins help map out the physical space of buildings, businesses and organizations around us, often with more accuracy than Google Maps or other location services. By using the data of 45 million users, the company has created a kind of crowdsourced map, or as the company calls it, “venue polygons.”

Beyond mapping location data around the world, Foursquare is also mapping interests—in the process, profiling its users based on where they eat and shop and what they say about their experiences. The company learns your habits—what restaurants you like, when you visit them, and what you order. Using a variety of tactics like sentiment and time analysis, Foursquare can build a cache of personal information it then uses to provide you with suggestions on where to go in the future. (Some of those suggestions will be delivered on behalf of Foursquare’s advertising partners.)

The idea of your mobile device telling you where to go next is still fairly new. The company only rolled out real-time suggestions last fall. Foursquare is still experimenting with how to deliver the best possible suggestions in hopes of ultimately turning your mobile device into the friend that plans your next night out.

I sat down with Crowley to talk about the decision engine Foursquare is building, and how that factors into the future of anticipatory computing.

Building The Check-In

ReadWrite: What was your idea behind Foursquare? Where did you see it when it began compared to now?

Dennis Crowley: Back in 2009, I had a company before this that we brought to Google called Dodgeball. It was very much about how to use mobile phones, awareness of where all your friends are, and the way they’re moving through the city. We were working on that project at Google before we left, and we realized that even though check-in was really interesting in the right tense, what was really interesting was if you had all this check-in data going back months or years. What could you do with that?

Could you predict the types of places that people would want to go to and can help people find places and neighborhoods that their friends have been to that they’ve never known about? That was early exploration with Foursquare. Now we fast forward; this company’s five years old, and it’s a big part of what we’re doing.

How do we make software for mobile phones that enables people to find discover all these hidden gems in the real world that are all over the place, and could be in your neighborhood, they could be round the corner from where you work, or could be in a new city? How could we get all the signal that we’re getting from all over the world to help people find these awesome things that are in the real world?

RW: Can you talk a little bit about Foursquare demographics?

DC: We’re at 45 million users at this point, and we still see somewhere between 5 and 6 million check-ins per day. In 2009, 2010, we had that explosive growth in Japan, and were surprised to see it picked up all through Europe and through Southeast Asia. If you look at it now, there are three markets that are growing very quickly, which are Brazil, Russia and Turkey.

We’re all the point now where our revenue model in the U.S. is working very well, with six different revenue generating products, four of them advertising-based. How do we take those advertising products, and bring them to the international markets that are proving to be very successful for us? Can we monetize those markets as well? It’s a big part of a lot of stuff we’re thinking about this year.

Foursquare-Powered Apps

RW: We talked earlier about the Foursquare API. Something like 50,000 developers have accessed it. How do you work with developers or encourage developers to implement Foursquare for either locations services or other parts of the application?

DC: A lot of the usage of the API is tagging the places. So it’s [like], I took a photo, a video, soundfile, creating a blog post here, which is great. I think there’s a lot of other things that can be done with the API.

Some of the interesting [uses] with Flickr, for example, you can tie your Flickr photos to your Foursquare. Pinterest is using Foursquare places to power your custom list. With Uber, you can say “Hey pick me up at JFK,” which is powered by the Foursquare data set. That stuff is pretty great.

Early on, we were really selling the API to folks—not with money, but like, “Hey, you should use our platform, it’s better than what’s out there.” It was tricky in the beginning, but now it’s the default location database that people use. It’s really rewarding for this team to see an app of the week that people are talking about on TechCrunch, and see they’re doing something with location and using the Foursquare API.

RW: So the API has been open for as long as Foursquare existed?

See also: What Microsoft’s Foursquare Deal Means For Developers

DC: Since the summer of 2009. I remember Naveen [Selvadurai, cofounder of Foursquare] and I had to decide: do we want to build an Android app, or an API? If we build the API we can get an Android app out of it. And we got a Blackberry app, and a Windows app. And 10 other things got built on top of it. Then it blossomed into a huge developer community.

RW: So going back to the location-based services, sometimes I try to get my friends to use Foursquare, and people are a little worried about security. What do you think about security? What would you tell somebody who says that?

DC: People think that Foursquare has a tendency to know where you are all the time. We’ve made it very explicit—it’s when you check into places. That’s when we share externally, when we share with your friends, Twitter, Facebook.

So I think most people that have been like, “I don’t know if that’s for me,” maybe they don’t fully understand the product or the privacy model, which is a little bit our fault. Maybe we haven’t done the best job in the world communicating that.

Overall for people who use the service everyday we very rarely if ever hear complaints of, “I didnt mean to share this.” That’s the whole point of the check-in. It hasn’t been a big thing for us.

Our Mobile Devices Will Tell Us Where To Go

RW: Let’s talk about anticipatory computing. What does Foursquare envision people doing before or after the check-in?

DC: The check-in is a means to an end in a lot of ways. It’s a mechanism by which people tell us about the real world. Google has this amazing knowledge and understanding of what’s going on in the Web, and where to find stuff in the Web because they have software robots and crawl the links.

We do that for the real world, but we don’t have robots. People go out and and experience places and tell Foursquare about it, and Foursquare can have a great understanding of the real world.

We know about the shapes of places, we know which places are interesting in the morning versus the afternoon, and the seasonality of them. Are they trending up or down? Is it less popular on Wednesdays or Saturdays? What are the brunch places in this neighborhood that your friend has been to that none of your other friends have been to? It’s a really powerful data set.

What we wanted to do with Foursquare since the beginning, before Dodgeball, we were thinking about what you do when this thing [points to phone] is smart enough to understand what you like and what you don’t like. What direction you want to be walking and what places are interesting to you and what aren’t.

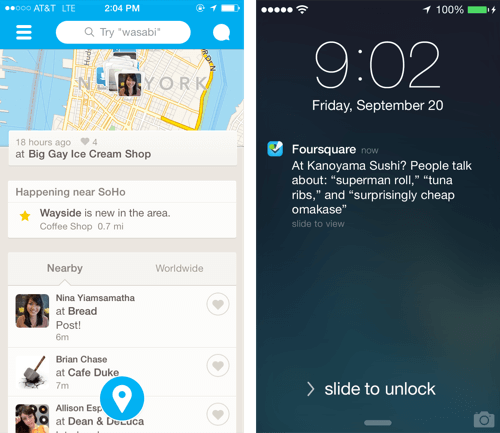

How do you pop things up in front of you so you don’t have to be on the phone all the time? All the goodness of Foursquare is locked in a thing which is hiding in your pocket. So how can we get Foursquare to wake up at various times and then let the user know, “Hey we found something awesome around the corner that you didn’t know about,” or “Hey, you just sat down at this restaurant, you have to order this particular dish.” The mechanism that we are using right now, your phone buzzes and you take it out of your pocket, and you’re like, “Oh Foursquare has something cool to tell me about this place, this neighborhood, this moment.”

We think about how this is going to change over time. Is it always going to be in the phone? Will it extend to your car? Will you be wearing it on your wrist, or your face? If you’re asking me about the Foursquare API, what can it do?

Right now we’re powering a whole bunch of apps that are helping people make sense of location. Eventually I think the Foursquare API will be powering a whole bunch of hardware devices, and a whole bunch of different things that are designed to give people really strong contextual awareness.

Everything we’ve been doing in the last 4 or 5 years has been leading up to things like this. We can run software in the back of your phone. We can push messages to screens that don’t just live in your pocket but live elsewhere.

RW: For people that aren’t necessarily familiar with contextual awareness or anticipatory computing and suggestions, can you explain to a Foursquare user why these notifications will be beneficial and what data Foursquare is using to suggest the local coffee shop?

DC: It’s a little bit of everything. The number one signal is probably the check-in history that you have. Every time a user checks into a place, it gives Foursquare an understanding of, do they like this place more than this place, this neighborhood, more than that neighborhood, this time of day more than that time of day? Do they like to go to a lot of new places? Or the same places?

We have a really good understanding of a lot of users because the Foursquare community has given us a lot of check-in data. For brand new users, if those users have some friends that are also on the service, you can take advantage of that. Even though I may not have a lot of check-ins in Chicago, a lot of my friends have been there, so I can draft off the places they’ve been to. What are the places that all my friends have gone to here? Which suddenly makes the city more accessible.

What we’re starting to get is, what can we know about a specific user’s specific interest in specific places? Do they go to these places all the time because they like the steak frites, or the bourbon cocktails or because they like cheap hot dogs or beer? How do we understand?

We’re doing a lot of work here to make this stuff a reality. How do we understand the specific things in specific places, and how do we steer people to specific things that are similar to those things at new places or neighborhoods or unfamiliar context.

We have so many signals coming in and out of our database. We can use all of that to personalize our search recommendations.

The Marauder’s Map

RW: So it’s not just the location—it’s also the tips, the sentiment analysis and taking and analyzing all of the data people provide Foursquare?

DC: It’s our ability to go through the one thousand tips that were left at any bar on the corner here to tease out, These are the 5 things that are most interesting here. People talk about: great beer selection, Irish car bombs, the curry fries and fish and chips. And those are the things that will gravitate to the top of the list, because people talk about them all the time.

Then we can associate the sentiment with each of those things and see everyone talks about this in a positive light, so that thing is really good. Everyone talks about this in a negative light, so let’s push those tips down.

See also: Behavior-Based Anticipatory Computing Coming To Social Networks

The moment my phone locks into a restaurant and it stays there for 5 or 6 minutes, the app that’s running in the background [can recognize] the phone stopped— it takes like 6 minutes to figure out it’s at Puck Fair. And then it’s like: what are the things that are interesting here? It’s the beer selection, it’s the curry fries, it’s the fish and chips; so let’s pop open the phone and let the user know that this is the thing that is the most interesting about this particular place.

It feels really magical when that stuff happens. It’s also still kind of primitive. Even though we have this amazing technical accomplishment that we’ve done, and this amazing technology base that allows us to do that, there’s a lot more work that needs to be done to make it feel personalized, and to make everything feel super special.

I’ve talked in the past about how Foursquare should be a version of Harry Potter’s Marauder’s Map—this external awareness of what people are doing and where they’ve been.

How do you make social networking tools that can be active when you’re not? How do you make things run in the background and make this ambient awareness of what people are doing, or the way that they’re moving, or are they close or are they far? And I think that’s what fascinates all of this team. When you do this stuff right it feels like super powers or it feels like magic. That’s what we shoot for.

No Longer Just A Social Network

RW: Do you even consider yourself a social network? I was looking at my own phone and I have Foursquare in the travel bucket instead of social.

DC: We’ve always had a social networking component, and it’s one of the things that drives our model. But really it’s about search and discovery. How can Foursquare take all this data that users have been giving us over the last 5 years, and how do we recycle that and give it back to people in the form of, “Hey we know something about this neighborhood that you never would have known otherwise,” and it turned out it was an awesome coffee shop recommendation that made your day.

How do we do that in a way that is proactive as opposed to having the user think about Foursquare, take their phone out of their pocket and do something? That’s going to be huge. Anticipating people’s intent, or anticipating people’s downtime or interest in ambient data and our ability to serve up really smart things about particular spots.

I don’t know any other companies that are approaching it as seriously as we are. There’s so much data that we’ve collected over the last couple years, so much technical infrastructure that’s designed to solve this one specific problem. We have a really nice head start over pretty much everyone else in this space.

RW: How often would I get a notification that says, “Oh, I see you’re walking down Broadway, I suggest you check out this art gallery.” What can someone expect for this future of Foursquare?

DC: We have the ability to do it often. I’m running a version of Foursquare on my phone that is very aggressive about the pings we send. What we’ve done for most users is we turn their dial down a lot because not every place is super interesting, and not everything interesting is brand new.

When you stop at a place, especially if it’s a new or interesting place, or someone has left a tip there, when you’re at the right place at the right time, then it pops up and says, “While you’re here you need to try this dish.”

That happens to me regularly, which is awesome. We can do that for people once a week, twice a week. At this stage where we are, I’m very happy about that.

The Future Of Foursquare

RW: How do you use Foursquare personally? Obviously you’re testing things all the time, but beyond that.

DC: I check into most of the places I go. I like to keep a record of the places I go, the social history is a part of it. I find a lot of places and share them with people. If I go someplace and I order something and say it’s awesome, then I’ll write a tip and share it with 4 or 5 people and say, “You have to try this fried chicken.”

See Also: 2014: The Year Foursquare Will Finally Be In The Right Place At The Right Time

I leave lots of tips, almost everywhere I go, I try to think of the one little nugget I want to leave behind for users to discover, and once a day or couple days I go through my Foursquare history and say, “I’ve left a tip at this place and this place.”

I found a really cool restaurant outside of the city this weekend, and I went to the ballet earlier this week and I have a great tip I left: “Make sure you read the program before the thing starts so you know whats going on.” [laughs]

RW: Do you think that there’s any company that has the amount of data on people at the scale that you do? It seems that there’s no one that rivals you with the personalization factor.

DC: Google has a lot of data about folks, and Facebook has a lot of data about folks. I think those are the two that are really being smart about putting this data to use and building amazing consumer services on top of it.

But remember, a lot of Google’s data comes from search queries on Web, or on phone, and a lot of the Facebook data comes from the news feed—it comes from what you’re doing with social connections, what you Like and don’t.

I think Foursquare data is super unique. It’s peoples’ relationships with places—it’s very specific. That’s one of the things we’ve done really well for the past five years or so, we knew that was our space. We’ve always stuck to that.

There were many opportunities in the company to say, “Why don’t we do this thing, or why don’t we do check into TV shows?” We kind of laugh at it now, but that was a big decision in 2009, 2010. Are we the check-in? Or are we people’s relationships to things in the real world? We were always doing the real world thing.

RW: Do you think how people use their mobile devices in the future is going to be reliant on their location? When you go out somewhere you get a notification that says, “I guess you’re going to the movies—why don’t you see this?” Afterwards, it says, “Why don’t you go to this restaurant?”

I just knowI personally use my mobile phone when I’m on the go more than being sedentary at the office or at home. Is that what you’re building Foursquare to head towards in the future?

DC: How do you build super powers into software? It’s the ability to know: the text messages you get that are annoying, and what do you want to do tonight. Foursquare is a mix of those things.

It’s like, this is where people are and these are the things that are interesting. You can imagine Foursquare will be very prescriptive: “Here’s what you do, go two blocks up and over, and go to this place and get the fried chicken. After you leave, go to this bar and get a drink and then go across the street.”

How much fun is it to go out with someone who really has a plan? How do we do this with software? How do we take all the experiences that your friends are talking about, all the things going on in New York or LA and put that in the format that is very easy to tease content out of?

RW: I feel Foursquare has solved my biggest problem. I’m that person who’s like, “What are we going to do tonight?” I always joke that my biggest decision of the day is figuring out where I’m going to eat dinner.

DC: If you me and Brendan [Lewis] all go to Google Maps and search for dinner or food, we’re all going to get the same results. That’s insane. It should be different based upon who you are, what you’ve done, your relationship to the place and what you were doing yesterday and what you’re supposed to be doing 3 hours from now.

All that contextual information lives in here [picks up mobile device]. It’s just a matter of teasing it out and cross checking it with a bunch of other results. We’re knee-deep in solving that problem, we just haven’t. There’s a little bit of a lack of awareness of how really good Foursquare is at solving search and discovery problems.

I think 2014 is the year in which we address a lot of those issues and start to change people’s perceptions.

Images courtesy of Foursquare