There’s been a bit of a firestorm lately over employers seeking Facebook passwords. Despite the outrage, employers occasionally have a legitimate need for access to documents in their employees’ social network and online service accounts. Cernam, a company that specializes in digital investigations, is looking to help employers dive into employees accounts without abusing the privacy of employees.

As I mentioned recently, I had a feeling there’d be a business in providing this sort of access to employee accounts. But I wasn’t thinking along the lines of forensic searches.

Karen Reilly, operations lead at Cernam, got in touch shortly after the story to say that the company is working on something similar to what I’d described, and what they call “Consent Based Capture.” Basically, this allows Cernam to collect evidence from Facebook, Gmail, Google Docs or other services based on consent of the employee.

Currently, Reilly says that Cernam offers products to bring “online evidence into every context where digital evidence is used today: If a matter is important enough to consider email evidence, it is essential to also consider online content.”

It’s not enough, she says, to provide just screenshots and printouts of Web pages. “At best they are a picture of evidence, and often not even an accurate picture. If you look at the area of e-discovery (use of electronic records in civil litigation) there is a huge emphasis on metadata in documents and emails, and on exchanging native formats rather than images of documents, so it is very clear that evidentially sound preservation is required.”

How it Works

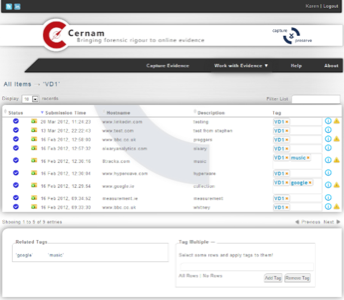

The current offering they provide is called Capture & Preserve. This isn’t a monitoring package; it deals only with evidence capture. Reilly says that it would come into play during a lawsuit or commercial dispute with a supplier.

“In those circumstances, a company needs to find and preserve all of the electronic records relevant to the lawsuit: emails, Word docs, spreadsheets, PowerPoints, etc. This is where the need for traditional digital evidence technology comes from, for example, products like Encase, the disk forensics tool from Guidance Software,” says Reilly. “Where we fit in is in relation to online content of all kinds – simple Web pages, blog posts and comments, social media content, message board posts, etc. In modern lawsuits something posted to Twitter or stored in Google Docs could be just as important as a formal document created in Word and found on a PC, so there has to be a way to properly collect and preserve that type of evidence.”

When companies request content to be preserved, the system creates what Cernam calls Online Evidence Containers (OECs). The OEC, says Reilly, is “a standalone portable evidence container based on the PDF standard, equivalent to a ‘disk image’ in the digital forensics world.”

The OEC provides the basic information any user would see online, plus more for “expert users,” according to Reilly. “An expert user, such as a digital forensics or e-discovery specialist, can access the raw evidence within the container in the form of network packets. These expert users will also find details of the system which captured the evidence, decryption material for accessing any SSL-encrypted data, and a set of secure digital timestamps based on GuardTime technology.”

Diving Into Facebook

Right now, Cernam access what’s available to anyone online. The Consent Based Capture system, though, would give employers access to Facebook, Google Docs, and other accounts controled by employees. Reilly didn’t provide specifics about the technology, but says that it would not be by providing passwords. “It never makes sense to give the password of any of your accounts to your employer. It’s dangerous for the employee, dangerous for the employer… the same password would give access to Gmail, Google Calendar, YouTube, Picasa, etc – all sorts of very personal but totally irrelevant information.”

Reilly says that Concent Based Capture “involves minimally invasive and fully automated searches, based on agreed parameters.”

“Minimally invasive means that if the company is looking for five documents to do with purchasing, they should get access to just those five documents, not download the entire contents of someone’s account,” says Reilly. “Fully automated means that this is ‘lights out’ search, no humans involved – no one in their HR or Legal department will be manually pawing through their Facebook messages, documents or emails – no human curiosity at play and no potential for accidental disclosures (e.g., someone planning to move jobs).”

The most important piece, says Reilly, is “agreed parameters.” The employee would see the terms of the search, and could deny the search if it’s overreaching. “If they are told that an issue involves supplier problems from last year, but they see a search going back 5 years, they can simply refuse consent.”

The service will work with Facebook, Twitter, Google Docs, Webmail services and “many other restricted or closed Web apps.”

Where is all of this stored? It varies, says Reilly. It could be a server within a company’s network, or with a third-party like the employee’s attorney who might review and confirm that the evidence is what was agreed-on before passing it to the employer. “In some cases getting consent will really mean bending over backwards, and we’re happy to help employers to do that.”

This sort of digital collection isn’t what most folks have in mind when they think about employers asking for Facebook passwords. But it is likely to come up time and again as people do more and more of their work on social networks.