ReadWriteBody is an ongoing series where ReadWrite covers networked fitness and the quantified self.

Over the years, as I’ve written about my fitness efforts and how I weave technology into my regimen of exercise and nutrition, there’s one question I get more than any other: How do I stick to it?

The easy answer is that I don’t. At least, not as perfectly and consistently as I’d like.

Like many other folks, I’ve seen my weight and fitness levels go up and down. I lost 58 lbs. nine years ago, then regained them. I then dropped 83 lbs. three years ago, only to gradually put 31 lbs. back on. I’m now on a kick to get back to lose 20 lbs., with the help of the latest available technology—and write about it for ReadWrite.

So far, so good: I’m pleased to report that since I started in August, I’m down 11 lbs. to weigh in at 195. I’d like to get to 185—maybe even all the way back down to 175. (I’m 5’8″, so even for my arguably sturdy frame, that’s still towards the high end of recommended weights, though those tables often draw criticism for not taking muscle mass into consideration.)

Do You Care To Share?

Over the years, there are only two fitness apps I’ve used consistently: MyFitnessPal, a nutrition tracker, and GymGoal, which records my workouts.

One reason is that they demand relatively little, and deliver a lot. Both remember recent and frequent entries, saving time inputting my activity and food intake. And both offer charts that give me a quick, visual look at how I’m doing.

The other thing I’ve noticed is that my usage of these apps is not particularly social. GymGoal only lets you share via email, and while MyFitnessPal has extensive social-sharing features, I find my use has dropped off.

When I was on a big weight-loss kick three years ago, I involved my friends by broadcasting my weight-loss milestones, gym check-ins and food-diary completions. I still do some of that, but I notice that they draw less of a reaction. (I suspect a few of my hipper-than-thou friends are liking or favoriting my posts ironically.)

And that’s fine, really. I appreciate the nods I get, and I hear that I inspire some of my friends to pay attention to their fitness. But mostly, I go about my fitness regime—offline and online—for myself.

See also: I Need To Put My Fitness Apps On A Diet

Karen Wickre, editorial director at Twitter, recently wrote about why—ironically, given where she works—she’s not tweeting about her own weight-loss effort: “I don’t care that much about every or step bite I take; why on earth should you? Add to that the fact that by nature I’m not inclined to much self-tout much.”

I’ve found that apps which emphasize group efforts, competitions, and badges—what some in the industry call “gamification”—are the ones I’m quickest to drop: SocialWorkout and Fitocracy are two I’d put in this category. They give me too much to think about, when sticking to my fitness routine is what I want to focus on.

That said, they might work for you, and I don’t want to discourage anyone from trying anything that spurs them to change their routines.

Finding The Motivation Within

While I’m not an academic, I’ve read some of the literature about fitness psychology, and a recurring theme from studies seems to be that intrinsic motivation is what drives people to the gym.

Intrinsic motivation—that internal push, innate desire, willpower—is the thing that most people find challenging to summon up. Extrinsic motivation—someone telling you you ought to exercise—is easy to get. But it’s unlikely to change your habits.

The right kind of extrinsic motivation, though, might become something intrinsic over the time. That’s where apps can help.

One app I’ve been experimenting with is GymPact, an app which charges you for every workout you miss and pays you for every workout you do, based on a plan you commit to in advance.

The payouts are minimal. GymPact CEO Yifan Zhang says that the company pools the money it collects from users who missed workouts, takes a cut, and then distributes what remains to the people who do work out. That typically amounts to 40 or 50 cents a workout, she says.

What really works about GymPact, it turns out, is the idea that people will lose money if they don’t work out.

“Fear of loss is stronger than desire for reward,” Zhang says. The result: 90 percent of GymPact users meet the weekly number of workouts to which they’ve committed.

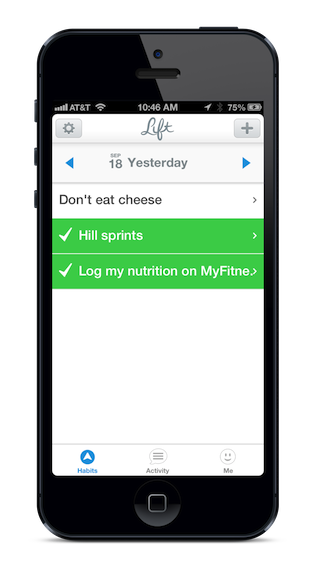

Another app I’ve used to strengthen my resolve is Lift, an open-ended goal-setting tool. This may sound bizarre, but I’ve actually set a Lift goal to log my nutrition in MyFitnessPal, turning it into an app that reminds me to use an app. The bottom line is that it works: Whenever I’ve slacked on logging my food in MyFitnessPal, I’ve tended to gain weight. Lift has helped me stay on track with MyFitnessPal, which helps me stay on track with eating right.

Integrating Fitness

There’s one other intriguing idea from the scientific literature to think about. In a 2010 article, the International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity noted the idea of “integrated regulation.” Here’s how the authors defined that term:

Integrated regulation is represented by an individual’s belief that a behavior is an important part of his or her identity and is consistent with his or her personal values. An individual who demonstrates integration might go running because they believe they are ‘a runner’ and therefore running is consistent with their sense of identity.

That reminded me of a recent conversation with RunKeeper CEO Jason Jacobs. I noted that I didn’t really think of myself as a runner—I picked up running recently because it was an outdoor activity I could do with my dog. Jacobs responded that I’m actually more typical than I thought: Most RunKeeper users don’t think of themselves as runners, he said.

I may not be a runner, but for a non-runner, I sure log a lot of miles on running apps. What does that make me?

After years of thinking of myself as a fat guy who was athletically inept, I find myself committing surprising acts of fitness. By announcing—quietly or loudly, to myself or to a crowd—that I am paying attention to what I eat and how I exercise, I shift my conscious definition of self.

When we post a selfie on Instagram, we’re announcing who we are—as much to ourselves as to our followers. Perhaps the same is true when we record a meal or a workout. The audience is not what matters. The action is.

When it comes to fitness, perhaps we are what we do. Our bodies are programmable. We just have to find the app that lets us log into our true selves.