[Updates are posted below the main article.]

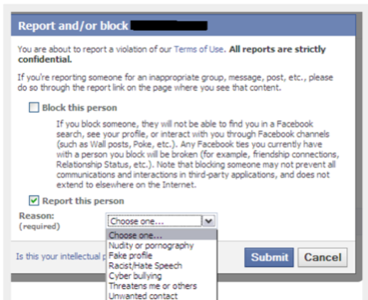

North Africa has become a testing ground for a new sort of online harassment, and ReadWriteWeb is in the middle of it. Groups of Islamists are using the proliferation of Facebook’s public pages to single out users they consider ideologically unorthodox (a broad category indeed by their definition) and then using Facebook’s public ban process to stop their mouths.

Once a target is identified, groups of allied Facebook users report the target as defying terms of service. Once a certain number of users mark a profile to be blocked, Facebook automatically does so. How do we know? Because our French editor, Fabrice Epelboin was one such target.

On ReadWriteWeb France, Epelboin published a translation of a post by Jillian York that identified this phenomenon. Epelboin summed it up.

“(A) group was created on Facebook (in Arabic) for the sole purpose of reporting, and thus having removed, Facebook profiles of atheist Arabs. The group, which appears to have also been removed, was entitled ‘Facebook pesticide’ and its sole purpose was to ‘identity Atheists / Agnostic / anti-religion in the Arab world and specifically in Tunisia …’ Once identified, the group members would then attempt to report such users.”

Although the post by York was modestly received in the original, in the RWW translation, it was very popular and attracted over 200 comments. One of the commenters on this post was “Hannibal,” the apparent leader of a group who banded together to block Epelboin’s Facebook profile. If he had not been been able to speak directly to Facebook’s French PR representative, he would have automatically been banned, as others have.

“All of this started when groups and fanpages became public,” Epelboin said, “allowing those guys to make some list of profiles to be harassed on Facebook, taking advantage of a loophole in Facebook’s crowd-sourced moderation process when it comes to banning profiles: if a few dozen members alert Facebook about one profile as being a fake, it is automatically deactivated.”

Facebook has been informed of this situation. They’ve been quick to console but slow to act. This policy remains in place. We hate to say we told you so, but, you know. We toldyou so.

Second update: Facebook’s public relations representative in France, Sarah Roy, verified that accounts are blocked automatically, via a bot, despite Mr. Axten’s assertions below. Hopefully, now that Mr. Axten knows this, he and Ms. Roy can get together and unblock these maliciously banned accounts. Perhaps this will lead to rethinking Facebook’s crowdsourcing of bans.

Update: Simon Axten, Privacy and Public Policy Associate at Facebook, responded after the post was published. Here’s his response.

The assumptions made in the blog post are false. We don’t take any action on a user report until it has been investigated by our professional reviewers, and they have positively identified a violation of our policies. Specifically, we’re sensitive to content that includes pornography, direct statements of hate, and actionable threats of violence. The goal of these policies is to strike a very delicate balance between giving people the freedom to express their opinions and viewpoints – even those that may be controversial to some – and maintaining a safe and trusted environment.

People whose accounts are disabled are notified the next time they try to log in and directed to a help page that explains why they were disabled. This page also allows them to make an appeal if they think they were disabled in error. These appeals are reviewed by our team as quickly as possible.

Facebook has always been based on a real name culture. This leads to greater accountability and a safer and more trusted environment. People can control who is able to find them in searches from the “Search” privacy page. They can also control who can see their connections on their profile from the “Friends, Tags and Connections” privacy page.

As of posting time, the press representatives from Facebook have not responded questions we sent on this issue.

Screenshot by Jillian York