If Facebook were a country, it would be the 3rd most populous country on earth behind China and India – but now Facebook thinks it can play Switzerland and lead a push for world peace. I’m not so sure that’s a good idea.

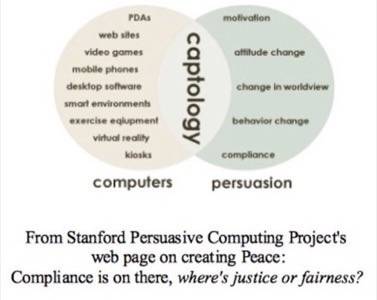

Facebook and the Persuasive (no, not pervasive, persuasive) Technology Labat Stanford launched what they call the “dot peace” campaign today. There’s reason to pause before enthusiastically supporting the effort. There are other ways that Facebook could make the world a better place and there are some reasons why the company deserves caution more than trust when it comes to its political agenda.

Facebook is a company with a political or cultural agenda, make no mistake about that. Company executives, including founder Mark Zuckerberg, have long said that Facebook seeks to move the world toward increased sharing of personal information in order to increase empathy between people. They believe that’s good for world peace (and Facebook’s valuation, of course). Some people might argue that minding your own damn business is good for world peace, but Facebook has a different strategy.

Sometimes that means working to change peoples’ expectations of privacy. All’s fair in love, war and social networking, perhaps, so more power to Facebook for seeking to tilt the balance towards sharing and away from privacy. Users could vote with their feet, or their browsers in this case – but that’s complicated by the fact that Facebook keeps all the social capital users build up locked into its system if they want to leave.

That’s big picture background, but here are three reasons why Facebook’s role in a movement to foster world peace deserves to be questioned.

Set the Data Free, Already

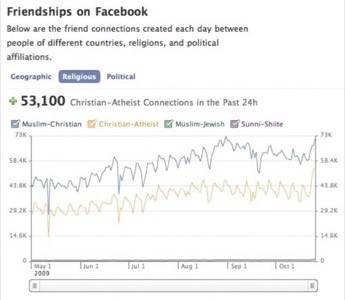

The new Peace.Facebook page has some really interesting data displayed on it, showing how many people from opposite sides of historical conflicts have become friends on Facebook over the last 24 hours, surveys about the viability of peace and other information.

That’s great – but imagine how much more understanding of the contemporary human condition could be derived from making that data and more freely available in anonymous aggregate for the rest of the world to analyze. These are “neat tricks” Facebook is doing with slices of its data – but isn’t the lesson of the age that a network of minds is generally more effective at innovating than any one company can be?

This is an ongoing part of the story and one we’ll have a lot more to say about in coming weeks and months – but for now we’ll just say that if Facebook really wants to change the world for good it should open up its unique birds-eye view of our behavior and interactions.

In the 1960’s anti-racist activists were able to prove that banks were systematically denying mortgage loans to African Americans. Redlining, as it was called, was exposed through analysis of data. When data is opened to analysis, patterns can be discovered – some of them unjust acts of systematic violence. The world is an unjust place and the social activity of 300 million people on Facebook will inevitably be useful in exposing some of those patterns of injustice.

Shallow Political Analysis

The first example of peace-through-Facebook you’ll find highlighted on the new Peace.Facebook page is a march organized in the nation of Colombia against the leftist insurgent group FARC.

As writer Eric Eldon put it a year ago on VentureBeat: “Thing is, right-wing Colombian guerrillas with close ties to the country’s U.S.-backed government have also been implicated in numerous terrorist activities. That topic seems to have been covered in much greater detail by European media than their counterparts here in the U.S… If I were Facebook… I’d think hard about using that example.”

The group protested against, the FARC, is one side of the longest-running civil war in the world. They may be a violent, authoritarian, drug-corrupted bunch of thugs but their opponents are a shadowy paramilitary group made up in part of Colombian police who remove their uniforms at night and chainsaw off the heads of civilians in towns suspected of offering FARC support. The US is deeply implicated, in bad ways, and it’s a seriously ugly situation. It’s among the worst in Latin America and there are some pretty gruesome stories about Latin America in the 80’s in particular.

Facebook wants to pick sides in that fight? People may argue that it was a march against violence that was organized on Facebook, but that’s one of the most violent countries on earth and Facebook refers to the march as anti-FARC. Since when is organizing street protests against one party in a brutal, decades-old fight a means of helping “people better understand each other?”

That looks like a dangerously shallow understanding of how the world works and what the obstacles to peace are.

Peter Thiel

Facebook’s first and most important investor is PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel. Thiel is a big believer in what’s called The Singularity, defined by the Singularity Institute as “the technological creation of smarter-than-human intelligence.” Thiel believes that investing in the Singularity means thinking ahead about how humanity can benefit from our relationships with these smarter-than-human machines instead of being hurt by them. He says that the Singularity will either lead to the biggest economic boom in human history or it will lead to an apocalypse. Literally.

Facebook’s machine intelligence is very real; its system is learning quickly about how humans interact and how different people respond to different events, for example. Let’s hope that the very wealthy Thiel, the very young Zuckerberg and the rest of the company’s insular brain-trust can steer that machine towards truly helping humanity and not making an even worse mess of things.

Given this dodgy philosophical background, it would be easier to trust Facebook as a humble servant of a global movement for world peace – doing its part by facilitating communication and opening its data to observation by the world at large. Instead we get very selective data interpretation done behind closed doors and presented to hundreds of millions of people as a way to take action.

I can’t help but feel uneasy about all this, as much as I enjoy using Facebook.