Most technology companies have vague mission statements that put a feel-good gloss on how they make money. This weekend, Facebook actually lived up to its claimed ambition “to make the world more open and connected.”

On Sunday, CEO Mark Zuckerberg, for the first time, joined the company’s contingent of gay and lesbian Facebook employees and their supporters—some 700 of them, by the company’s estimates—to march in San Francisco’s Pride Parade. It was an unusually ebullient moment, given the past week’s Supreme Court decisions striking down both California’s ban on gay marriage and a federal mandate not to recognize such relationships.

The Rainbow Connection

At the same time, the company shared some statistics that suggest the social network has had a role in raising awareness about gay and lesbian rights. In the United States, 7 out of 10 Facebook users in the U.S. are connected to a user who has “expressly identified as gay, lesbian, or bisexual on their timeline,” Facebook reported. Some 25 million users changed their profile picture, a spike in activity that often reflects a thematic response to holidays or news events.

See also: The Internet Goes Red & Pink In Support Of Marriage Equality

While Facebook didn’t come out and say it, it’s entirely reasonable to think that the rise of social media played a role in accelerating the shift in views.

Zuckerberg’s presence at Pride was just the latest gesture of support by the social network, which has a long history of friendliness to gays. One of its cofounders, Chris Hughes, is gay; when he married Sean Eldridge, Facebook created a same-sex marriage icon for the couple and others like them to post on their timelines.

Tomorrow The World

The challenge for Facebook: Can it take its campaign for openness global? Can it, in short, export the Northern California values of its workforce around the world?

A spokesperson for Facebook said the company would “decline to speculate” on how Zuckerberg’s appearance in the Pride Parade would play with Facebook users overseas, which leaves us with the job.

A disclosure is warranted here: I am gay and have lived almost my entire postcollegiate life in San Francisco. Since 2008, I’ve been in a marriage that the Supreme Court only recently decided the federal government must recognize. I also have gay friends who work at Facebook.

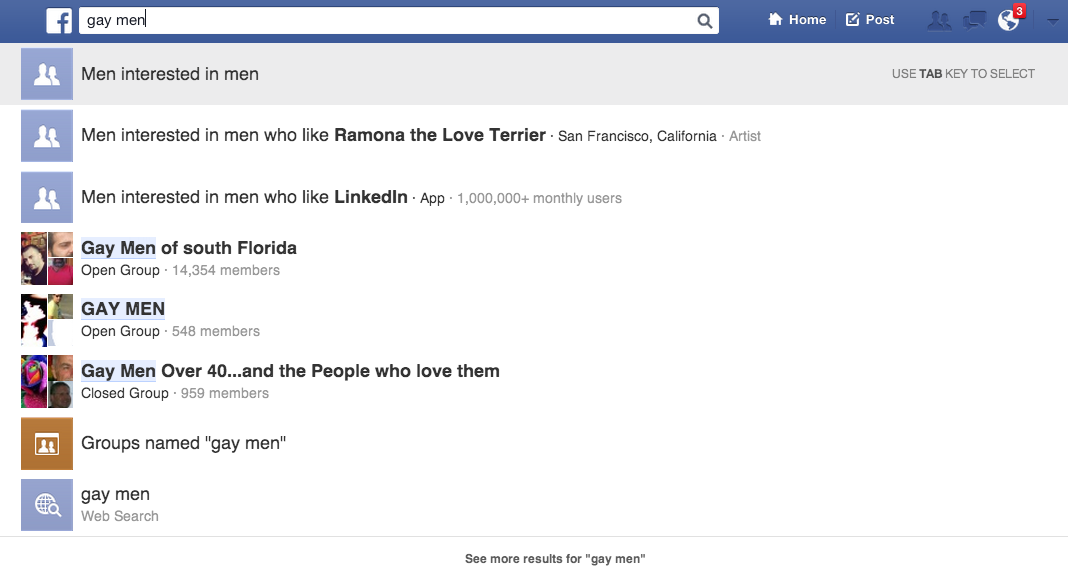

Interestingly, Facebook has never had an option that allows you to identify as “gay” or “lesbian” in your profile. Instead, you list your gender, and the gender of people you’re interested in. Do a search for “gay men” on Facebook, and Facebook’s Graph Search feature gently corrects you to look for “men interested in men” instead. (That’s why Facebook had to analyze users’ timelines, rather than the data in their profiles, for expressions of sexual identity.)

Hilariously or sadly or simply illuminatively, many Facebook users in countries outside the United States don’t seem to recognize the implied sexual nature of this interest, leading to far more “men interested in men” and “women interested in women” than you’d expect. Once you get past the knee-jerk giggles, it’s a sign of how the cultural values of Facebook’s designers and engineers inevitably shape the product in ways that don’t always travel well.

Reaching The Next Billion

Currently, India is on track to becoming the biggest country for Facebook. It’s projected to overtake the United States and Brazil in 2014. Indonesia is likewise growing quickly. Neither country is known for being particularly friendly to gays or lesbians. Many countries in Africa have even more hostile regimes.

Facebook’s next billion users will come from places where it’s much harder for gays, lesbians, and bisexuals to be open and share.

That’s the sobering thought that Facebookers, gay and straight, must face. As laudable as it is for them to stand up for equal treatment at home, many of their users face far greater struggles for equality. In some countries, even using Facebook can put gays and lesbians at risk if a “friend” exposes them.

In that regard, Facebook is no better or worse than the societies it operates in. Yet Zuckerberg’s stand on Sunday suggests that the company aims not just to reflect the world, but to improve it.

That is the hope—dare I say, the missionary zeal—that surely motivates Facebook employees. (Let’s be real: I doubt most of Facebook’s rank and file board their shuttle buses every morning pumped up to sell ads.)

The tension they face is how to make this a natural outcome of a platform for connecting people, not an all-too-American company’s mission civilisatrice. It risks a blowback among the very people it hopes to reach and bind together in a more tightly linked world. One of Facebook’s internal mottos for employees encourages them to “move fast and break things.” I’m not sure that approach works for complex social issues like gay rights.

But perhaps I am too timid.

Another Facebook slogan asks: “What would you do if you weren’t afraid?”

Maybe what you’d do is openly advocate for what you know in your heart is right.

Photos courtesy of Facebook