Don’t laugh, because this is going to sound a little weird: let’s talk about the ethics of virtual pets. Sure, it’s probably not something you’ve thought about a lot, but consider it for a second. As mixed reality becomes more mainstream, virtual companions will get more popular and more realistic, engendering more attachment. Arising from this phenomenon will come some interesting social and ethical issues.

So, let’s talk about it. But first, some history:

Digital companionship is nothing new. The ’90s gave us Dogz and Catz, and we saw Tomagotchi and Digimon emerged a little later, eventually giving rise to whatever the heck this thing is. The 2000s brought more immersive titles like Nintendogs, more connected ones like Neopets, and mobile-first ones like Neko Atsume.

See also: Are virtual reality standards long overdue?

Dictated by the technology of the time, these pets all shared one thing in common: they lived on screens. Whether on a keychain, Game Boy, TV, or iPhone, owners were only able to interact with them through a UI, walled off from our day to day reality. Like fish in a tank, they were nice to look at, but were essentially relegated to a separate, parallel universe distinct from our own.

Now let’s jump to the present. The emergence of VR and MR is closing the gap between real and virtual pets, freeing them from the fish tank, increasingly enabling them come into our world. Like our real companions, virtual ones can interact with us, recognizing and navigating our physical environment. They even have some advantage over real pets – they don’t make messes (or ungodly smells); their level of interaction can be up to the owner (no dog yapping at passing cars, no aloof cat); and they’re endlessly customizable (own a huge dinosaur, or a cute robot).

And here’s where the ethics thing comes in. Let’s start with some basic questions, like “shouldn’t we just be paying attention to other people instead of virtual pets?” Well, sure, ‘other people’ are great, but there’s a reason why we, say, play video games (or for that matter have real pets), a lot of which has to do with ‘other people’ not being so great all the time. As we’ve mentioned, virtual pets have been around for a while, and we don’t see them going away anytime soon “Okay, shouldn’t we just pay attention to real pets instead?” Again, sure, if you’re willing and able to care for another life responsibly and consistently, within the realistic constraints of time, emotional investment, and critically, money.

And that’s where it gets trickier. It’s strange to frame it this way, but the “pet industry” is very much a thing. Gone are the days when most pet ownership is a functional decision, when our dogs were keeping dangerous wild animals at bay and our cats were protecting our grain supply from rodents. Pet ownership nowadays is largely driven by our desire for companionship, and a $60+ billion industry has grown up around that desire. The virtual pet industry—past and future—is no different.

Let’s fast forward. Imagine a not too distant future in which REXY, your daughter’s beloved Mixed-Reality pet dinosaur, has been helping teach her responsibility for the last two years (heck, let’s throw in an educational module, so it’s also been teaching her basic arithmetic). The company that created REXY shuts down, gets acquired, or pivots its strategy to first-person shooters, and decides to stop hosting and supporting her software. You, as a responsible consumer, understand the vagaries of the market. It’s just business. But good luck explaining to your daughter why her companion has suddenly disappeared, or is dying a slow, glitchy death before her eyes.

Pay up or this virtual dog gets it

Let’s say the company doesn’t shut down or get acquired, but instead switches to a freemium model. To keep her dinosaur (and your virtual dog, to which you’ve also become attached) alive, is it ethical to for that company to charge you money? If so, how much? There are certainly precedents for questions like these in non-virtual pet ownership, but it gets more fraught in a digital environment. Forget for a moment about paying for functional or cosmetic alterations, let’s think about freemium survival: instead of paying for food, can your virtual dog just wear an advertiser’s branded collar? Could REXY occasionally interrupt your daughter’s math lessons to extoll the virtues of Fruity Pebbles? If the company pulls support, what if hackers exploit a security flaw in REXY, and start teaching your daughter something else entirely?

With the proliferation of emerging technologies and in the absence of industry leadership, such dystopic speculation can run rampant. But the fact remains that, as Mixed Reality comes to the fore, companies like mine will create digital entities with which people will form real attachments. It’s up to us to ensure that the rollout will be thoughtful and ethical.

We need to plan for a continuity of experience robust enough to withstand events that often happen to companies, like security breaches, pivots and acquisitions. We need to realize that, while virtual companions aren’t going away, they’re not a replacement for real companions, so engagement and retention strategies used by app and game developers must be applied judiciously for the good of the user. And we need to be wary about monetization, about using our users’ attachment to their virtual pets to extract payments from them.

Yes, there’s a brave new world of pet ownership on the horizon. But we, as an industry, need to ensure we’re on the right side of history when the dinosaurs rise again.

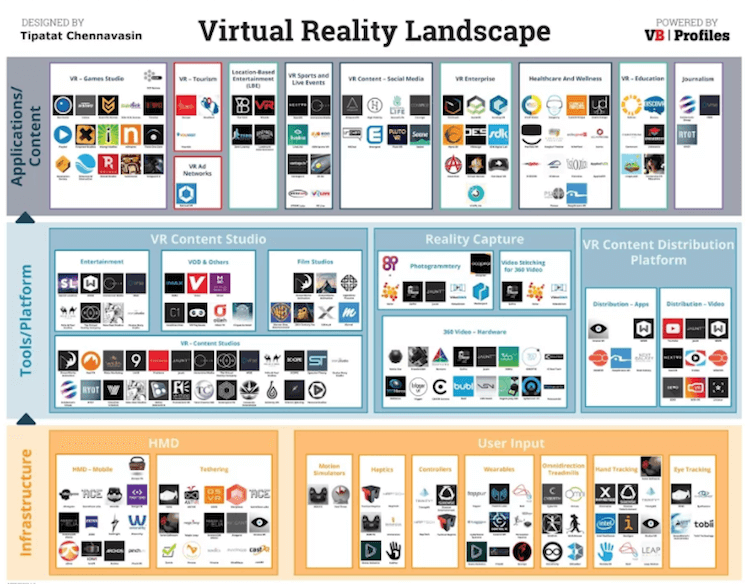

This article is part of our Virtual Reality series. You can download a high-resolution version of the landscape featuring 431 companies here.