Email is a problem. But what kind of problem? That depends on the workplace. And two very similar companies are coming up with very different solutions.

Tiny Speck, which is opening its work-collaboration service, Slack, to the public on Wednesday, aims to untangle inboxes for workers drowning in information. Cotap, a startup recently launched by early Yammer employees, is targeting employees who don’t have email at all.

Both companies are based in San Francisco; Tiny Speck has 18 employees, while Cotap has 17. In a huge market for communications tools that’s getting upended by the rise of mobile devices, there’s likely enough room for both products to thrive.

Email: Can’t Live With It, Can’t Live Without It

The average office worker spends 28% of their day dealing with email, and another 33% gathering information and collaborating internally, according to the McKinsey Global Institute.

Yet companies in large sectors of the economy—including many of the largest U.S. employers, for example—don’t offer employees email, relying on break-room flyers or briefings by managers to pass directives down from headquarters.

It’s an information feast or famine, depending on what kind of job you have.

Both are large markets: There are about 615 million “knowledge workers” in the world, Cotap estimates—typically people with company-provided email addresses. Yet there are about 2 billion total workers, which suggests the non-knowledge-worker market may be twice as large. And all workers need a competent communication tool.

No Worker Left Behind

At both Slack and Cotap, past jobs shaped the founders’ visions for the product.

Cotap CTO Zack Parker dropped out of high school and worked at a toy store and Jamba Juice before eventually landing a job in technology.

“I always knew that I was smart,” Parker said. “It took me a long time to build up a resume that showed that I had something valuable to contribute.”

Parker recalls working at a Jamba Juice where the store manager didn’t let workers serve a special Halloween smoothie “because he thought it was satanic.”

“It was a kooky, weird place which might have been a more normal, integrated place if we could have talked to other people in the company,” he said.

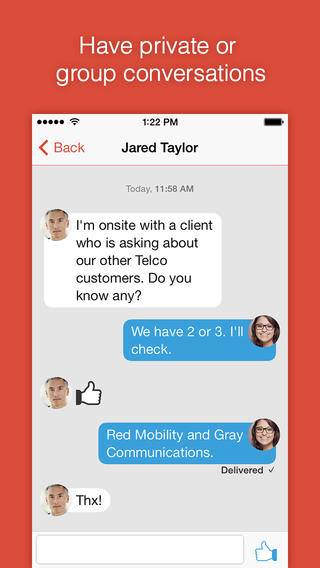

Cotap’s mobile app aims to bridge the gap between frontline workers and headquarters by offering a text-message-like communication experience without the need for employees to share their phone numbers. It takes design cues from popular messaging apps like WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger: For example, you can simply acknowledge a message with a thumbs-up icon.

Parker thinks this will make workplaces less hierarchical: “Everyone is reachable by everyone in the company.” As a result, the employees who work directly with customers and have good ideas can become more “visible” to colleagues in headquarters.

Cotap hasn’t set pricing yet, but it plans to launch a paid version of its service this year.

Cutting Colleagues Some Slack

Butterfield, meanwhile, vividly recalls the horrors of the corporate email systems at Yahoo, which acquired his photo-sharing startup, Flickr, in 2005. He had to constantly file email into folders, and then remember which folder he put it in.

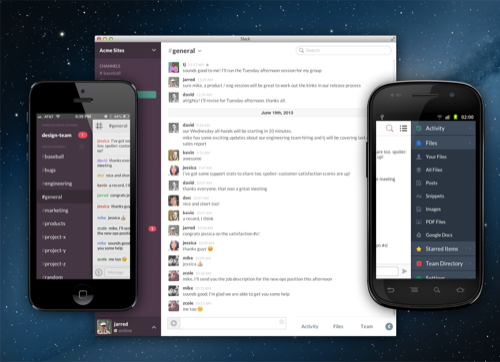

At Tiny Speck, Butterfield swore he would run the company without email, and his team built internal tools based on Internet Relay Chat to accomplish this goal. The company’s first product failed—an online game called Glitch—but Butterfield kept a small team and turned Tiny Speck’s communication tools into Slack.

Besides email lists, information workers are inundated by email-based notifications—bug reports, customer-service tickets, server-status updates. Slack pipes updates from Dropbox, GitHub, MailChimp, Crashlytics, and others—all the modern tools an app developer or other tech-product company might use—into a common workspace and makes them quickly searchable.

Slack also smartly distributes notifications to desktop and mobile devices. An unread desktop notification turns into a mobile push notification, for example, while read messages are neatly synched across devices.

Slack is offering a free version of its service with storage and message limits, as well as a paid version for which it will charge $8 per user per month.

The Mobile Future Of Work

The differences in the products show in their usage. Slack has 16,000 users, but only 57% of those users log in using both mobile and desktop on a daily basis, and activity among Slack customers usually takes a dive on the weekends.

As Butterfield told me last year, Slack is primarily “for people who sit in front of computers all day”—coders, product managers, and other tech-infused office workers.

Cotap, meanwhile, is a much simpler mobile-only product, though it’s considering a desktop version, and users are often active outside regular working hours.

“People check in every morning,” Parker said. “We chat on the weekends. It’s brought people together more as friends than as coworkers. It’s created this sense of always being able to interact with each other.”

Despite the products’ differences, it’s interesting how Slack and Cotap both anticipate a post-email economy. Butterfield points out how Cozy, an online rent-payment startup he’s advising, had to add text-message support for younger tenants who “never check email.” Cotap is aiming to serve workers who never get overwhelmed by work email because they never got it in the first place.

Parker thinks Cotap’s mission will inspire prospective employees.

“When I’m talking to candidates, people just don’t often in this industry have a sense for what a bubble we live in,” he says. “Candidates get excited when they realize there’s a much broader set of people they can reach.”

Butterfield hopes customers will get excited about the prospect of slaying the email beast. In early tests, some customers found it reduced their email volume by 75%.

And there’s a rising sense that email’s just not the universal communication tool it once was, especially for younger employees who’ve grown up with texts and messaging apps.

“There isn’t this idea [anymore] that email is the canonical way to communicate with someone,” Butterfield said.

Photo of Zack Parker courtesy of Cotap