There will be two completely different concepts of the PC application in the next version of Windows, which we can probably expect to be generally released by the fall of next year. The “Desktop application” will continue to follow the usage model with which we’ve been generally familiar since Windows 95, and whose evolution up to now has been incremental and followable.

Then there is something called the “Metro app.” Today we know more about what a Metro app is. As for what it does, that remains an open book, though perhaps not for very long. Most of the Build 2011 conference here in Anaheim will be devoted to explaining the Metro app, and we’ll need every word of it. We’re now seeing the initial foundation of a completely new Microsoft ecosystem that is not around Windows applications, .NET applications, or Windows Phone apps.

There will be two applications platforms cohabiting Windows, starting with Windows 8. They will not share the same space on the Desktop. In fact, the Desktop will be shoved literally to one side to make room for the new platform.

Yet there will be no transition that developers will have to make, or be compelled to make, from the conventional Windows applications we have come to rely upon (like Word and Outlook) to Metro apps. There is no platform exodus in the works – this from the highest levels of the company. Microsoft Windows Division President Steven Sinofsky has told RWW he intends for Desktop applications to remain a permanent part of Windows, since he does not foresee Metro ever rendering them obsolete. Too many programs, he said, require the fine-grained detail and precision control that a mouse or even a trackpad provides.

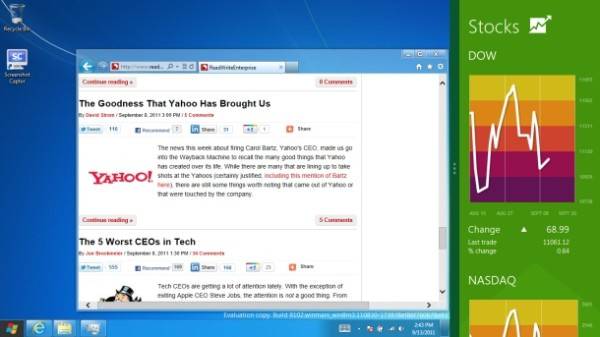

However, as we were told by Microsoft program managers, using exactly these words: The Desktop is another app. Although we’ve been advised not to take this too subjectively, there will definitely be two concurrent classes of Windows applications. The second class will be the Desktop where Office presently runs. For the first time in Windows, the Desktop appears as an app, installed as a tile within a new device called the Start Screen. This is a multi-page staging area for Metro apps using the tile model introduced in Windows Phone 7, as well as for launching Desktop apps and the Desktop itself. The Start Screen completely contains a staging area for the new Metro apps.

(For the sake of clarity, I use the terms “application” and “app” distinctly, not interchangeably. An application is designed to enable its user to perform a complex job, usually in the form of some kind of document. An app is a simpler program that usually performs one function, presenting some form of information to the user. One exception may be a game, which is usually a pretty complex program, often with a unique usage model, but at least explained simply enough.)

A lot of back and forth

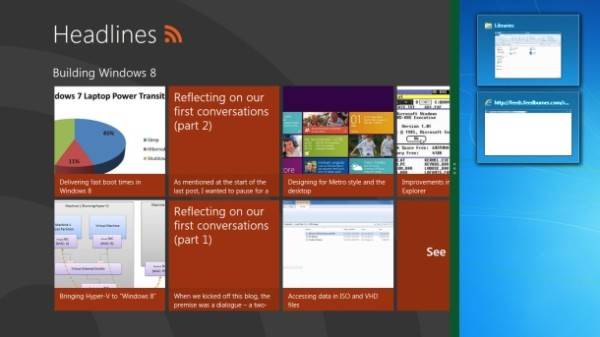

When the user logs on to Windows 8 (more on the changes to that process in an article later this week), he will not see the Desktop, but instead the Start Screen. If you’ve used an Android phone, you’re familiar with the Home Screen which flips left and right to reveal a larger staging area for apps than will fit on just one screen. The Start Screen is similar in some regards. It starts on the far left page of a horizontal strip several pages long. Each page contains tiles (in landscape mode, three or four tiles tall depending on the monitor) that represent Metro apps and some system services.

Each Metro app may actually be running, at least in some small part, within its alloted tile space, just like tiled apps in Windows Phone 7. For example, a social media connector may automatically pan through individual pictures of your online friends, in a lively manner that keeps the screen active.

From what we have been able to discern so far from the early developers’ preview, what would make a good Metro app is essentially the same functionality that would make a good mobile app. By definition, it’s lightweight and tactile. It performs a basic function and does not produce documents that need to be saved, maybe with the exception of the occasional photo retouching app.

One example shown above is an RSS news reader, which isn’t any more complex than what you’d find on the simplest mobile phone. There’s no obvious menu bar in a Metro app. Instead, when an app has functions or commands that you can choose (the only way you find out is by trying), you flick down from the top edge or up from the bottom edge of the screen. (If you flip your tablet to portrait mode, it’s still the top or bottom edge – you don’t suddenly flick a different edge.) A list of functions called the AppBar pops up always from the bottom (even if you flicked from the top).

The Taskbar retains its place on the Win8 Desktop with only slightly cosmetic differences over Win7. But the Start Button (by default, on the lower left side) no longer brings up the Start Menu. Instead, it switches back to the Start Screen and the Metro staging area. The Windows button on the keyboard (pressed by itself) and the Windows button on tablet screens perform the same function; when you’re at the Start Screen, both bring back the Desktop.

Nothing more starkly characterizes the distinctions between the two worlds of Desktop and Metro than Windows 8’s new feature for letting you move the boundaries between the two. With multitouch, you can flip between apps like shuffling cards in a deck one-by-one, by flicking from the left edge of the screen slightly to the right. This brings up the next app in sequence, and you keep this up to find the app you want. (For keyboard users, the old Alt+Tab method still works.)

But there’s a unique trick with any two Metro apps, or with a Metro app and the Desktop: You start to flick, then stop and back up just slightly. This snaps the app you’re about to bring up onto the left column of the screen (about 25%). A boundary pops up between the two, and you can shift that boundary with your finger. You can keep an app docked to one column while you flip another open app (or the Desktop) into the adjacent space.

Metro apps are specially geared to run not only in the reduced space of their tiles on the Start Screen, but also within a 25% column along the left or right side. In fact, I saw a demonstration of a developer preview of Microsoft Expression Blend where an app’s column view was defined as a separate resource. The Desktop now has a kind of a “column mode,” showing thumbnails of open windows. However, you cannot split the screen between the Start Screen and the Desktop, only between a Metro app and the Desktop.

The new System menu

For the first time in Windows, there’s a new system menu with five basic functions, once again very reminiscent of the “dock” buttons on Android phones. They are always the same five buttons, and in Windows 8, they are called charms. (Don’t call them icons, that’s a no-no.) From top to bottom: Search, Share, Start (again!), Devices, and Settings. With multitouch, you bring up the System menu by flicking from right to left on the very right edge of the screen, as if pulling up some hidden panel from the right-hand side.

The meanings of some of these charms changes depending on what you’re doing at the time. Specifically, Settings enables a Metro app to bring up a menu of options that pertain to that app. This way, there’s always one way to obtain settings for what you’re doing: flick left from the right edge, touch Settings.

If you’re using a mouse (which for Windows 8 is indeed an “if”), pointing toward the very left corner of the screen (not clicking, just pointing) brings up a popup form of the System menu where the Start Menu used to be. This takes some getting used to, because my first instinct after the last 17 years of using Windows is to try to find applications by clicking the Start Button.

The Search charm is the new tool for locating programs. Clicking Search brings up a list of things that can be searched or that can do searching. Search doesn’t exactly behave the way we expect it to. If we’re on the Start Screen, for instance, and we touch Search, our first set of choices includes searching through Apps, Settings, or Files. When we move to the Desktop, however, our first set of choices is searching by way of Metro apps. That seems weird, but we’ll just have to get used to it: Many Metro apps are capable of responding to search requests, by way of a new feature in Windows 8 called contracts. Essentially, something in the system does an “all-hands” call for anyone who can search, and the Metro apps respond.

We’ll be testing Windows 8 throughout this week. If you’d like us to try something, leave us a note in comments and we’ll give it a go. Later this week, we’ll look at the Two Faces of Internet Explorer. In Win8, there’s an IE10 for Metro and an IE10 for the Desktop. And yes, they’re separate.