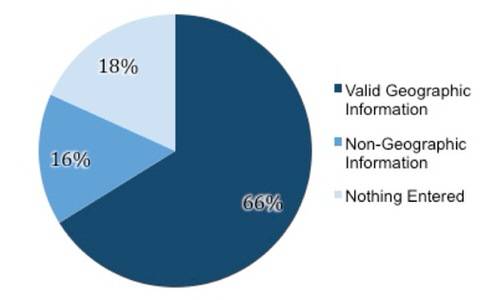

The first in-depth user research study on the usage of the “Location” field within Twitter profiles has just been published by the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC). With a sample size of 32 million English language tweets in hand, PARC summer intern Brent Hecht selected a group of 10,000 active users to study. Remarkably, he found that 34% of Twitter users do not provide a valid geographic location on their Twitter user profiles. Instead, some of these users co-opt the field to make jokes, express their love for a particular celebrity or to shout back at Twitter that their location is “NON YA BUSINESS!” Others, meanwhile, provide no location information at all.

For any related service or other research study that leverages this field to determine Twitter users’ actual location, the implication is obvious. Without first parsing the tweets to remove those that don’t use the location field as intended, the sample data could be corrupted. PARC already found one study where that was the case.

To perform their analysis, PARC researchers collected 32 million English language tweets from the Spritzer sample feed, a feed of 1-2% of all tweets, selected at random and delivered in real-time. The tweets were created by 5,282,657 individual Twitter users. A random sample of 10,000 active users (those have more than five tweets in the data set) was selected from the feed. Then from that group, the researchers extracted and examined the location field.

66% Report Location, but That Doesn’t Mean “City, State”

Only 66% of Twitter users had entered any sort of valid geographic information into this field, and the term valid is being used loosely here. For example, the researchers included someone who wrote they were from “kcmo – call da po po,” as having entered a valid geographic location – Kansas City, Missouri. They also included those who just shared what continent they were from or those who provided a fake city name (e.g. “Bieberville”) alongside a real U.S. state (“California.”)

In reality, the actual percentage of those who provided a true city/state combo was much lower, but PARC did not specify by how much.

Location: “Justin Bieber’s Heart:” Jokes and Other Sentiment Found in Location Field

From the 34% who did not provide real location information, there were a number of trends spotted. One was that the field was often used to denote appreciation for a particular celebrity. Celebrities the researchers came across here included Britney Spears, the Jonas Brothers, Jedward and, of course, topping the charts with 61 users mentioning him, Justin Bieber.

Another common trend was using the location field to express a desire for keeping that information private through the use of phrasing like “not telling you,” “none of your business,” etc. Also frequenting this field were insults (“looking down on u people”), non-Earth locations (“outta space”), sexual content, jokes and even an expression about how much someone hated their current location. (for example, one user said he was from “redneck hell”).

What This Means for Researchers Analyzing Twitter Data

That wasn’t the end of the PARC study, however. The researchers also popped the portion of their dataset (the 16% who had not provided a valid location) into Yahoo! Geocoder, a tool that converts place names and addresses into latitude and longitude coordinates. Instead of returning errors, Yahoo! Geocoder provided coordinates for 82.1% of the data. For example, “Middle Earth” was determined to be north of Lubbock, Texas, “BieberTwon” is in Missouri, “somewhere over the rainbow” is in northern Maine and “wherever yo mama at” is in southwest Siberia.

?What this means, of course, is that research studies that simply enter a Twitter dataset into a geocoder will have corrupted results. Geocoders assume that all the information they’re given is geographic, so it will attempt to locate these coordinates. To accurately determine location from a dataset of tweets, the data should first be pre-processed by a geoparser to separate geographic information from non-geographic information.

Unfortunately, not all Twitter user studies have done this. One well-known research study from 2007, “Why We Twitter: Understanding Microblogging Usage and Communities” by Akshay Java, Xiaodan Song, Tim Finin, and Belle Tseng, did not use a geoparser, the PARC researchers found. (See coverage on ZDNet, SmartMobs or EdTechTalk, for more on that study.)

Although that doesn’t necessarily discredit all of the study’s findings – it looked at a number of trends, from type of Twitter updates (links, chatter, replies) to categories of Twitter users (info sources, info seekers, friends), too – it should be noted.

More information on PARC’s Twitter research is available here.