This week, the ad industry blasted Microsoft’s use of a privacy feature called “Do Not Track” in Internet Explorer 10, threatening to override it entirely to barrage your browser with targeted ads. But you know what? It doesn’t matter. A little-known privacy feature in Internet Explorer means that Microsoft, and Web users, have already won this battle.

Ryan Gavin, Microsoft’s senior director of Internet Explorer, reminded ReadWriteWeb that both IE9 and IE10 contain a privacy feature called “Tracking Protection,” which prevents user information from being passed to a website. While Do Not Track is a more gentlemanly request for anonymity, Tracking Protection simply shuts your browser’s mouth, as it were, and refuses to say almost anything.

Microsoft has said previously that IE10, which will make its first appearance in Windows 8, will ship with Do Not Track on by default – in other words, your browsing activity won’t be tracked by advertisers right out of the box. That has left advertisers fuming, since user information is exactly what the advertiser needs to provide high-value, targeted ads. Those targeted ads typically cost more, generate higher revenue and provide a more useful advertising experience than a generic ad designed for the Internet at large, advertisers say.

On Monday, the Association of National Advertisers sent Microsoft chief executive Steve Ballmer a letter claiming that the ANA believes “that if Microsoft moves forward with this default setting, it will undercut the effectiveness of our members’ advertising and, as a result, drastically damage the online experience by reducing the Internet content and offerings that such advertising supports”.

In other words, according to the ANA’s executive vice president of government relations, Dan Jaffe, less ad revenue means the Web’s “free,” ad-subsidized services may go away, replaced by paid subscriptions or other methods. “And if you get less revenue for websites, it threatens to have less information that’s available to consumers for free,” Jaffe said in an interview. “And [site operators] start to put up paywalls, and some of these paywalls as you read in the press have not always turned out well for consumers.”

The ANA has its own voluntary advertising opt-out service at Aboutads.info, which automatically scans your machine for cookies and other trackers, then gives you the option to opt out. Still, that works only for a given browser and computer (since opting out is stored in a cookie) and only for the “participating” companies. The ANA advises that you periodically revisit the site and opt out again and again.

What Is Do Not Track?

The Do Not Track movement surfaced in 2007, when the FTC was petitioned to create a list of websites that would not be permitted to collect information from a user’s Web browser, somewhat similar to the “Do Not Call” list used by home phones. Mozilla developers added a custom plug-in to the browser than enabled DNT about a year later. Then, in 2009, Firefox began implementing it, even on mobile devices. Google’s Chrome will add DNT support by the end of the year, a company spokesman confirmed, and IE, of course, will enable it in IE10. Opera already includes DNT support.

DNT is an HTTP header that “asks” Web sites to not collect user data. But compliance is voluntary, and far from widespread. So far, only 1 of 211 top Web sites surveyed adheres to DNT principles.

Microsoft’s perspective is that customers should get what they pay for, and that includes privacy. “Competing on privacy is a good thing,” Gavin said. “Consumers win when you have a point of view, as we do, that someone paid us money for Windows. Part of that is Internet Explorer, and – it’s called Windows Internet Explorer, incidentally – and giving them choice and control over privacy is a good thing, and we have incentive to support and respect our paying customers.”

Microsoft’s moves haven’t been well-received by some. Apache, which powers a substantial number of the world’s Web servers, has already said that it won’t honor IE10 Do Not Track requests, precisely because turning it on violates consumer choice, in Apache’s view. Or, as Jaffe puts it: “What Microsoft is doing is claiming it’s preserving consumer choice, but what it’s doing is imposing its choice on consumers.”

Tracking Protection

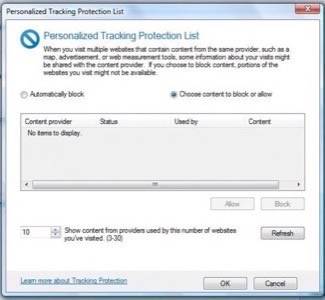

To enable Tracking Protection in IE9, go to the Settings>Safety>Tracking Protection menu, then enable your personalized list via the “enable” button in the bottom right-hand corner. You can also set up the list by telling IE how many times you wish an ad to be displayed before it gets axed. (CNET has a video tutorial if you want more.)

That enables what Microsoft’s rivals call a “draconian” measure, blocking the website or tracker from getting any information about you. But Microsoft’s response is that if the sites themselves aren’t honoring DNT requests, then it has a right to enforce the consumer’s will.

“Our job is to really just to say we’re going to keep consumers safe and protected online,” Gavin said. “Do Not Track doesn’t actually do much, unless… someone’s honoring that signal. I don’t have a crystal ball for when that may or may not happen, and when there would be conformance or not.

“But we have a thing called Tracking Protection in IE10. Tracking protection is something we enabled with IE9, and instead of, where DNT sends a signal to a website saying, ‘Mark does not wish to be tracked,’ Tracking Protection actually stops tracking from happening at the browser,” Gavin added. “We can actually go through and subscribe to what’s called the TPL or Tracking Protection List, that can be curated by any number of groups, or individuals – you can even have one that’s built dynamically, based on sites you’re going to, and we actually don’t send signals. So when you’re in that list, we say, ‘Ah! So-and-so’s ad network is looking to add a single pixel tracker,’ so we can actually stop that. We can stop the tracking from happening.”

You won’t find Tracking Protection, or its equivalent, in any of the other browsers. But ad-blocking plugins exist for Firefox and Chome, which simply prevent the ads from being shown in the first place. The ANA’s right in that blocking ads prevents websites – including this one – from displaying the ads that generating the revenue needed to keep the site up and running. On the other hand, if it’s true that major websites are ignoring consumer requests to prevent tracking them, it’s hard to argue with Microsoft’s logic.