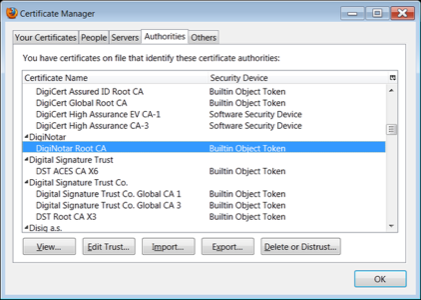

Tuesday morning, Chicago-based authentication services provider Vasco Data Security announced its DigiNotar subsidiary, which issues certificates for SSL used to secure financial and other discrete transactions online, detected a security breach that forced it to issue improper certificates. One of those certificates, it admitted, was for Google.com.

It would be a shocking occurrence if it weren’t so common. A root certificate authority (CA) is, by definition, the starting point for all trust in the Web transaction system. It self-signs its own certificate as a way of validating its own validity. Thus when DigiNotar’s validity isrevoked, as it was yesterday by Mozilla, among others, all the certificates it signs – including the one for itself – lose their authenticity.

“The problem is much bigger than this one incident,” Sophos senior security researcher Chet Wisniewski tells RWW. “The whole idea that we ‘trust’ all of these entities shows that we have outgrown this model and the only safe thing to do for the moment is to remove them.”

That may be safe, but so is staying locked up inside your house forever. Earlier this month, RWW’s David Strom suggested the introduction of “public notaries” for root certificates. Under such a system, users could choose the notaries they trust, and change that choice as conditions warrant.

Some have argued that such a system is technically no different than what we have now: a series of largely unknown entities like DigiNotar that users never hear about until something goes wrong, and which they have no legitimate reason not to trust until then. Last April, after the authority incident to affect DigiNotar took place, security researcher Moxie Marlinspike wrote that the difference here lies in the user’s ability to distrust one entity and choose someone else instead – a difference that could introduce a modicum of competition.

“It seems reasonable to think that we’ll need to anchor our trust somewhere. That we’ll pick some entity or group of entities to authenticate our communication. And right now, I could identify a set of organizations that I would trust to do this effectively. But what seems insane is to think that I could identify an organization who I would not only be willing to trust right now, but forever, without any future possibility of changing my mind based on that organization’s performance. If we’re locked into making a single decision now that will affect us forever, what incentive is there for the trust provider we select to act in a way that will continue to warrant our trust?”

Marlinspike has devised his own working model of one of these notaries, called Convergence. He gave a briefing about the concept at the recent Black Hat security conference, shown in the video below.

Wouldn’t the adoption of a notary system simply move the weakest link in the trust chain to a new location, and make that location the target of attack from whatever wants to call itself the Iranian revolutionary army?

“The idea is somewhat complicated to explain. You remove CAs entirely from the process,” responds Wisniewski. “Then you pick a notary you trust (perhaps you run your own, you may choose to trust Moxie and the [Electronic Frontier Foundation] as well). When you surf to Gmail, you grab its cert. You also ask these notaries to grab Gmail’s cert. You then compare that the one you are getting matches these third parties. If they match, you know you are not being ‘man-in-the-middled.’ If you decide the EFF is no longer safe to not corroborate with your government to intercept and send you a fake cert, fine. Dump them and choose a different notary. Since there is no centralized authority that you must trust, you can choose and change your trust as you wish.”

By “man-in-the-middled,” Wisniewski is referring to an attack process discovered last year by security researchers Christopher Sogohian and Sid Stamm (PDF available here.) The process takes advantage of the fact that some CAs will be receptive to requests from government authorities (which Wisniewski also referred to above) who wish to used forged certificates to convince suspects of their authenticity. Such CAs will often give these authorities fake certificates signed by them, which suspects’ browsers will then accept as legitimate.

It then becomes a trivial matter for a malicious entity to effectively impersonate the government entity. What’s more, it isn’t necessary for that entity to spoof the CA that signs the real certificate, but rather any legitimate CA (which is why a DigiNotar signature can be accepted for a google.com certificate).

Sogohian and Stamm wrote:

“When compelling the assistance of a CA, the government agency can either require the CA to issue it a specific certificate for each website to be spoofed, or, more likely, the CA can be forced to issue an intermediate CA certificate that can then be re-used an infinite number of times by that government agency, without the knowledge or further assistance of the CA.

“In one hypothetical example of this attack, the US National Security Agency (NSA) can compel VeriSign to produce a valid certificate for the Commercial Bank of Dubai (whose actual certificate is issued by Etisalat, UAE), that can be used to perform an effective man-in-the-middle attack against users of all modern browsers.”

Perhaps more importantly, Sogohian and Stamm discovered, an actual industry was being formed around so-called turnkey intercept solutions that enable other agencies (or anyone, for the right price) to use this method automatically to compel fake certificates from CAs.

“Placing trust in more than 600 certificate authorities to be honest and not screw up, is quite a leap of faith,” writes Sophos’ Wisniewski. “Be sure to enable certificate revocation checks in your browsers and take a close look at alternatives like Convergence.”