Civilization began with a dam. By controlling the flow of water, rulers rose to power in ancient Egypt and China.

Just as water was the lifeblood of agriculture, content—photos, videos, links, status updates, and check-ins—is the lifeblood of the social Web. And those who would rule our digital worlds seek to have content pool up and flow at their command.

(Yes, in most cases, “content” is a loathsomely generic term. But it’s hard to think of a better catch-all description that embraces all the varied material that flows between the Web’s social services.)

Like water, the torrents of data generated by the billions of people online can never be fully controlled. But they can certainly be harnessed. And every node of connectivity between these networks is a potential flashpoint for border skirmishes.

Looked at in this light, it makes perfect sense that Tumblr went to Yahoo for $1.1 billion. Thanks to years of neglect of properties like Flickr, Yahoo was a social backwater. Without a pool of social updates to call its own, Yahoo would always be subject to the whims of Twitter, Facebook, and the rest. Now it is part of the flow.

Battle Lines

Just like water in the physical world—a scarce, well-guarded resource—these flows of content can turn contentious.

Just ask Instagram, which saw Twitter cut off access to its list of friends, and retaliated by requiring an extra click to see images. Or Path, which lets photos flow to Facebook but had the return flow abruptly (and quietly) cut off earlier this year. Or how, last year, Twitter snubbed Linkedin, a longtime partner, restricting access to the tweets that used to show up on users’ online resumes.

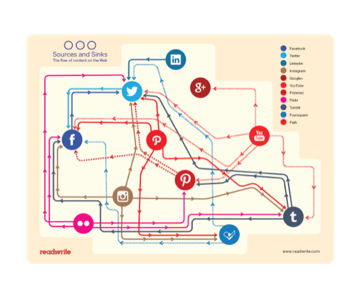

To begin to understand these conflicts, it helps to start with a map. For that, we’re borrowing a concept from hydrology—that of sources and sinks.

Sources And Sinks On The Social Web

Content must begin somewhere. These points of creation, like the upload of a YouTube video or the snapping of an Instagram photo, are sources.

It must likewise end up somewhere. The nexus of creation is not always the natural place of consumption. For example, on Path, the mobile-focused social network, a substantial number of users opt to share moments on Twitter, CEO Dave Morin recently told me. That may seem odd, considering Path’s limitations on the number of friends you can add, but it allows users to reach more people with updates that aren’t especially private.

And a large reason why Instagram became so big so fast—and was courted by Twitter before it was bought by Facebook for a billion dollars—was that it was so easy to share photos not just on Instagram but on those larger social networks. By establishing itself as a source to those sinks, Instagram emerged as a powerful pool of visuals in its own right.

Foursquare, which began as a source for location check-ins posted out to Twitter and Facebook, may now be more important as a sink for other apps’ check-ins—in particular, Instagram, where many photos are tagged with a location derived from Foursquare’s vast database.

Precisely because these flows have value, they are points of leverage and vulnerability. Yet they also show the social Web’s fragile interdependence.

Twitter And Facebook: A Sinking Feeling

The world’s most important social networks have long battled over their lists of friends. Early on, Facebook invited Twitter to be one of the first apps on its platform. But in 2010, when Twitter added a feature to let people find their Facebook friends on its information network, Facebook abruptly cut it off. Since then, the two services have engaged in a tit-for-tat sparring.

After Facebook bought Instagram, Twitter cut off the ability to find friends on Instagram. Facebook did the same when Twitter launched Vine, its short-video app.

Yet while they fought over friends’ lists, they never cut off a mutual flow of status updates. You can use Twitter to update Facebook—and, confusingly, you can opt to automatically send your public Facebook statuses out on Twitter, too. That’s because while each service prefers to be the ultimate sink for content, it doesn’t want its rival to become a more powerful source.

LinkedIn, lacking the leverage over Twitter that Facebook holds, went from being what Twitter called “the perfect combination” in 2009 to something incompatible with “delivering a consistent Twitter experience.” After some worries that LinkedIn would feel less lively without tweets, the rift actually worked out for its media ambitions. It turns out that many tweets weren’t that professional in nature, and LinkedIn has moved from being a sink for tweets to a purer source of work-related information. Which, of course, it is now trying to have flow to more sinks.

There are more twists and turns and intriguing dead ends in these flows of content. Did you know, for example, that you can’t pin updates from Facebook to Pinterest—even if they’re posted publicly on a brand’s Facebook Page? Or that Google+ is a virtual island, rejecting crossposted material as “social spam”?

Here’s where the Web’s content flows stand as of 2013. For simplicity, we haven’t shown every possible connection. And events may swiftly make this map outdated. Last year, it certainly looked different. Next year, we’ll see new linkages and blockages. Like a fast-moving river cutting through the landscape and reshaping it as it goes, the only constant we can expect is change.

(Click on the image for a larger version.)

Photo by Saad Faruque; infographic by Madeleine Weiss for ReadWrite