Today is the 3rd annual international Data Privacy Day and a whole bunch of companies are listed on the organization’s website as participants. Google, Microsoft, even Walmart. Facebook is not listed as a participant and has stirred up a lot of controversy with changes to its privacy policy lately.

Why are these corporations singing out loud about protecting our personal privacy? According to the website, “Data Privacy Day is an international celebration of the dignity of the individual expressed through personal information.” More than dignity, this is about building trust with consumers so that these companies can do things with our personal data. Some of those are things we might like, a lot. Aggregate data analysis and personal recommendation could be the foundation of the next step of the internet. Unfortunately, Facebook’s recent privacy policy changes put that future at risk by burning the trust of hundreds of millions of mainstream users.

Facebook’s privacy changes were bad for two reasons: because they violated the trust of hundreds of millions of users, putting many of them at risk where they had felt safe before, and because by burning that trust in the first major social network online, the next generation of online innovation built on top of social network user data is put at risk.

Had Facebook opened up access to user data through users’ consent – then access to that data would be a whole different story. As is, the privacy change was unclear and pushed-through without user choice concerning some key data, putting the whole concept of users sharing their data at risk.

See also: Facebook’s round-up of other peoples’ statements about privacy today on its blog.

How Facebook Changed

This past December, Facebook did an about-face on privacy. (Here’s our extensive coverage of the changes and why they were made.) For years the company had based its core relationship with users on protecting their privacy, making sure the information they posted could only be viewed by trusted friends. Privacy control “is the vector around which Facebook operates,” Zuckerberg told me in an interview two years ago. 350 million people around the world signed up for that system.

Facebook’s obsession with privacy slowed down the work of people who wanted to build cool new features or find important social patterns on top of all the connections we users make between people, places and things on the site. (Marshall shared a link to The San Francisco Giants with Alex, for example.)

Those geeky cries in the wilderness to set the data free, for users to be allowed to take their data with them (“data portability”) from one website to another? Not going to happen at Facebook, founder Mark Zuckerberg said, due to privacy concerns.

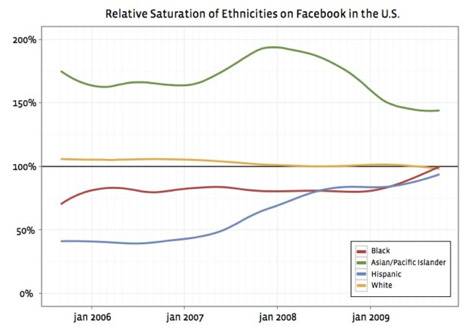

Aggregate data analysis? Facebook as a living census unlike any the world has ever seen? Back off, sociologists, you can’t access aggregate Facebook user data due to…privacy concerns, the company said. Facebook staff did team with a few outside academics they knew and studied that Facebook data themselves. They published some charts about racial demographics on Facebook, concluding that everything was peachy-keen and only getting better on the social network. But if you thought an army of independent analysts could glean some objective insights into the contemporary human condition out of Facebook, you were wrong.

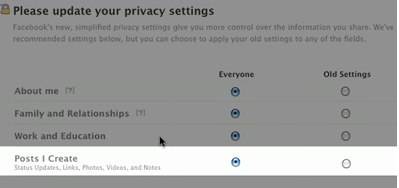

Then in December, things changed. Facebook began prompting users to re-evaluate their privacy settings. Public was the new default and some fields on a user’s profile were suddenly and irrevocably made visible to the web at large. Your photo, your list of friends and your interests as expressed through fan page subscriptions could no longer be set to private.

Sorry, 350 million people who signed up for the old system. When Facebook said in the fine print that it reserved the right to change its policies, the company really meant it.

The changes were responded to with an international wave of confusion and indignation. News stories were written all around the world about Facebook’s privacy changes – they’re still being written today. Yesterday the Canadian government announced it was launching its second investigation in six months into Facebook’s privacy policies.

Did Facebook Break the Future of the Internet?

Is it naive to think that things you post on the internet are really “private?” Many people say it is, but that was core to the value proposition that Facebook grew up on.

Presumably the companies working together on International Data Privacy Day don’t believe that privacy online is a lost cause.

In fact, trusting that your private data will remain private could be a key requirement for everyday, mainstream users to be willing to input all the more of their personal data into systems that would build value on top of that data.

Facebook is the first system ever that allowed hundreds of millions of people around the world to input information about their most personal interests, no matter how minor.

Will that information serve as a platform for developers to build applications and for social observers to tell us things about ourselves that we never could have seen without a bird’s eye view? That would be far more likely if more people trusted the systems they input their data into.

Think of Mint’s analysis of your spending habits over time. Think of Amazon’s product recommendations. Think of Facebook’s friend recommender. Think of the mashup between US census data and mortgage loan data that exposed the racist practice of real-estate Redlining in the last century.

Personal recommendations and the other side of that same coin – large-scale understanding of social patterns – could be the trend that defines the next era of the internet just like easy publishing of content has defined this era.

Imagine this kind of future:

You say: “Dear iPad (or whatever), I’m considering inviting Jane to lunch at The Observatory on Thursday, what can you tell me about that? Give me the widest scope of information possible.”

Then your Web 3.0-enabled iPad (or whatever) says to you: “Jane has not eaten Sushi in the past 6 weeks but has 2 times in the year so far. [Location data] The average calorie count of a lunch meal at that location is 250 calories, which would put you below your daily goal. [Nutrition data online.] Please note that there is a landmark within 100 yards of The Observatory for which the Wikipedia page is tagged with 3 keywords that match your recent newspaper reading interest-list and 4 of Jane’s. Furthermore…

“People who like sushi and that landmark also tend to like the movie showing at a theatre down the street. Since you have race and class demographics turned on, though, I can also tell you that college-educated black people tend to give that director’s movies unusually bad reviews. Click here to learn more.”

That’s what the future of the internet could look like. That sounds great to me. Think that vision of the future sounds crazy? How long ago was it that it sounded crazy to think a day would come when you typed little notes into your computer about how you felt and all your friends and family saw them?

But how many people will trust this new class of systems enough to contribute meaningfully to them, now that they’ve been burned by Facebook?

On International Data Privacy Day, it’s good to consider the possible implications of Facebook’s actions not just on users in the short term, but on the larger ecosystem of online development and innovation over time.

Photo: Mark Zuckerberg, by Andrew Feinberg