Here’s a very serious question: Are the tools your company’s employees use to do their job more or less motivating to that end than the apps, games, and social services they use to do something other than their job? Put another way, does the software your people use for play improve the quality of their work, more than the software they use for work?

This is a question that a company called Rypple first started tackling three years ago. Identifying what Rypple was, was evidently hard enough – in 2009, ReadWriteWeb called it an enterprise solution for garnering feedback; two years later, we re-introduced it as a tool for rewarding employees for good performance. Both were partly right. Fortunately for Rypple, Salesforce perceived it as something substantially greater, and today Rypple is being re-reintroduced as the latest cloud-based component in the Force.com arsenal.

What is it now? It frankly hasn’t changed all that much from its original mission – to be a feedback and motivational tool for a digital workforce. Salesforce is unusual among software companies for perceiving motivation as a principal component of IT. Then again, it’s already unusual for eschewing the use of the word “software” to describe its line of work.

“The way we started Rypple was, we thought the world would change. It was more social, more collaborative, less hierarchical, more real-time,” says Daniel Debow, Rypple’s former CEO, now the vice president for Rypple at its new parent company, Salesforce. Debow tells RWW, “Everybody’s expectations of both the tools and the way that they work was changing. The problem was, the things that were being given to them by the HR organization to help improve performance were designed for fifty years ago. None of these apps are truly social; they’re certainly not delightful. They’re basically automating forms, and they’re driven by the compliance requirements of an HR organization. We took a totally different approach to build Rypple, and it was very similar to a company like Zynga: a consumer-first approach.”

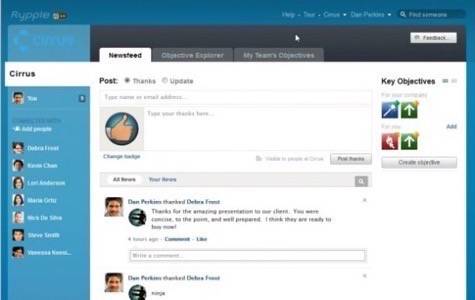

Debow demonstrated the new Rypple running on the Force.com platform. Its newsfeed provides a platform for ongoing conversation about the business. There, the manager can set variable-term goals for the workgroup sharing this feed as well as for one or more individuals within the group. These goals are represented by icons that appear within the “Key Objectives” column along the right side. Employees may use these icons to gauge their progress toward achieving these objectives. “It starts envisioning the world as a graph of objectives that companies do,” he remarks.

While the Rypple system is designed to cultivate verbal feedback, its principal tools are metrics and symbols. Employees need to see how well they are performing, and from time to time, to have some tangible proof that anybody in charge is truly paying attention to them, truly appreciating them. Annual evaluations are failing in the modern workforce, Debow explains, compared to real-time metrics.

“Instead of process automation, it’s behavior amplification,” he says, “Take the things that great managers do and make it easier for them to do it. At a high level, those are the things around goal setting and alignment, recognition in real-time, feedback that’s open and easy to give and get, and coaching.”

While on the surface this may sound ominous – an automated coaching algorithm, like something out of “The Martian Chronicles” – Rypple’s Debow believes that it actually takes digital tools like his to get managers more personally involved in the process. “One of the common misconceptions about usage of social applications is that it’s replacing face-to-face, or real interaction, with online virtual interactions. Nothing could be further from the truth. Great social apps encourage people to meet more often face-to-face – you see this with Twitter with meetups, and on Facebook with events.”

Debow imagines Rypple being used as a kind of background app for a manager and employee actually communicating – not just with IM, but face-to-face. The objective setting process can take place in an office, with the employee looking at the manager’s screen while he assigns them to her. “This is what I mean by encouraging more real-life, face-to-face conversations,” he says.

The part of Rypple that generated all the buzz last year was the use of badges – literally, on-screen graphics that look like sewn-on Scout patches – to reward workers for various accomplishments. At the time they were introduced, the badges took some heat. As software developer Frank Caron wrote for his personal blog, “The problem here is that these ‘status’ symbols are awarded by non-quantitative and subsequently arbitrary means. The only guideline for ‘earning’ a badge, in this context, is the small text description that accompanies the badge during the selection process. The onus is on the nominator, the person awarding the badge, and not the product itself to use the appropriate badge at the appropriate time.”

As Dan Debow describes Rypple’s badge system, the fact that the awards process is not based on some automated score is what ensures direct, personal involvement on the part of the manager in the awards process. Contrary to Caron’s description, badges in the new Force.com version are attributable to core competencies defined by the company (“leadership,” “taking charge,” “ethical behavior”) – tags for personal behavior that work like tags for articles on a blog. So employees can discern why they’ve earned a badge, not just that they’ve earned it.

“What’s amazing is, you can build these badges – they’re not top-down, they’re bottom-up,” says Debow, “so that badges reflect culture. They reflect the words and the means that people use with each other, rather than top-down, HR-speak. You describe the great things that others do in a language that they already use. It can be as formal or informal as the company’s culture requires.”

In the world of public social networks, individuals have become notorious for “gaming the system” – triggering avalanches of usually negative commentary that unduly influences the community’s ability to contribute to a ratings or voting process. What controls does Rypple provide for preventing employees from doing the same with its “social enterprise” network, with results that are more likely quantifiable in dollars?

“You can actually create rules around badging that can stop that kind of gaming, to create value and currency,” answers Debow. For example, individuals’ use of feedback or voting may be capped at the manager’s discretion, or only certain individuals may be empowered to bestow particular badges.

But it’s here that Debow risks breaking with his new boss, Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, by pointing out that behaviors in enterprise networks will tend to differ psychologically from those on public networks, where users tend to be anonymous and are not necessarily held accountable. “You cannot give an anonymous public comment in Rypple,” states Debow. “Your identity is there; people know what you say.” And just as how it’s hard to imagine two co-workers monopolizing a company meeting by behaving like social networks users – for instance, ping-ponging kudos with each other to build up their value and consume valuable time – it’s just as hard, he says, to picture these same people behaving in the digital social enterprise in a similarly contrived fashion.

“This is a big difference from traditional HR system design,” Dan Debow tells RWW. Where the old design tried to bake the rules into the system, therefore requiring an enormous amount of time and energy to set up – you have to deal with the hierarchy, rules, permissions, who’s visible, who’s invisible, what’s visible to whom, which always results in extremely expensive consulting – a socially designed applications relies heavily upon social norms inside of a company, and the fact that the systems are transparent.”

Rypple is available for existing Salesforce customers for an additional charge of $5 per user per month. Though the Rypple service is accessible now, its integration with Salesforce.com (pictured above) will be made available in April.