We live in a society where human health is increasingly enhanced by artificial augmentation and implantation including hip replacements and hearing aids. French company Carmat have been working for 15 years on the artificial heart, a device that completely replaces the human heart in people with end stage heart disease and a life expectancy of less than two weeks without the surgery.

They’ve recently announced their second trial, commencing in 2017 with the aim to achieve European approval for their device. The Carmat device differs to other robotic heart devices as it is meant to be used in cases of terminal heart failure, instead of being used as a bridge device while the patient awaits a transplant.

How it works

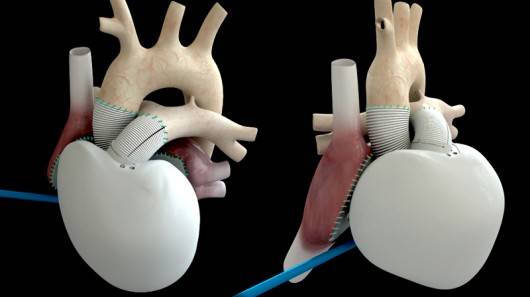

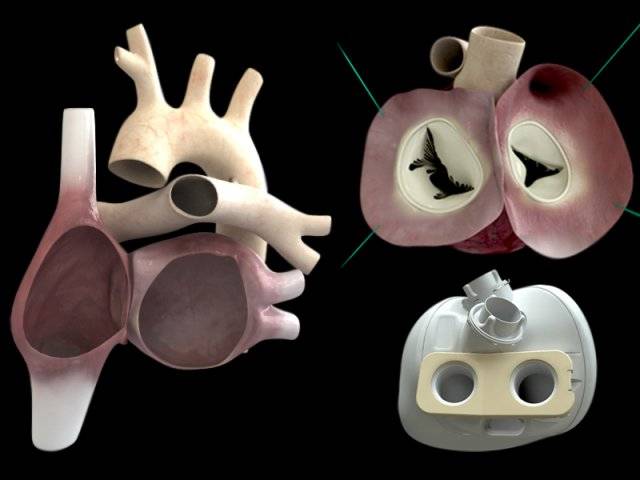

In Carmat’s design, two chambers are each divided by a membrane that holds hydraulic fluid on one side. A motorized pump moves hydraulic fluid in and out of the chambers, and that fluid causes the membrane to move; blood flows through the other side of each membrane. The blood-facing side of the membrane is made of tissue obtained from a sac that surrounds a cow’s heart, to make the device more biocompatible.

The Carmat device also uses valves made from cow heart tissue and has sensors to detect increased pressure within the device. That information is sent to an internal control system that can adjust the flow rate in response to increased demand, such as when a patient is exercising.

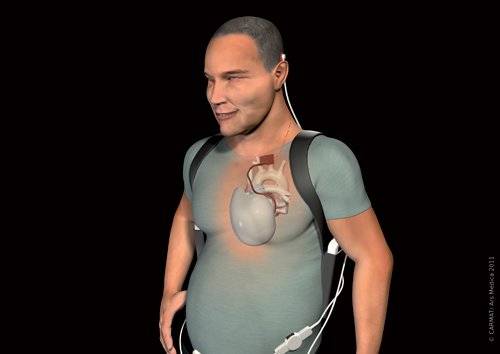

The heart is connected to external systems; a power supply, monitoring and hospital control system for the post-operative period and subsequent outpatient visits and a portable or wearable power supply and communication system for the patient to return home.

A new heart is not an exact science

So far, the success of their artificial heart transplants has been couched in research terms with success in the previous four person feasibility trial defined as survival at 30 days. Their model has been trialled on four people all of which have died.

Carmat’s first transplant patient, died in March 2014, two-and-a-half months after his operation apparently due to a device failure. The second died in May 2015, nine months after having been grafted. These two deaths had been caused by “micro-leakage of the blood area to the operating liquid of the prosthesis” having created a “disturbance electronic engine control” of the artificial heart, according to the analysis of Carmat.

The third died after nine months due to “respiratory arrest during chronic renal failure” and the patient was suffering “from a combination of severe diseases, especially kidney failure already diagnosed prior to implantation of the prosthesis and warranting regular hospital visits.” It was also stated that the heart continued to beat after the patient had died and that “the medical team turned off the prosthetic device on confirmation of the patient’s death.” The fourth and final patient died from medical complications associated with his critical pre- and post-operative state

The company is now pushing on with a trial aimed at securing European approval. It will enroll 25 patients and this time the endpoint will be survival at three months. Says Marcello Conviti, CEO of Carmat:

“Our target is to have all the data submitted by the end of 2017 and commercial availability in selected CE mark countries at the beginning of 2018,”

What is the future?

Clearly we’re a long way from the dreams of futurist tech predictors that for see a future where one’s heart beat could be regulated through their smartphone. Transhumanist Zoltan Istvan sees a future where “artificial hearts will be Wi-Fi-enabled and could be sped up with a smartphone to have wild sex when you want it and sped down to sleep better at night.” according to the International Business Times. He goes on to concede that there’s a potential risk that an artificial heart could be hacked.

There is however no demonstrable evidence that an artificial heart (or pacemaker for the matter) could be hacked. But the fear of course, is real. For example in 2014, former Vice President Dick Cheney revealed that his doctor ordered the wireless functionality of his heart implant disabled due to fears it might be hacked in an assassination attempt. Other research reveals that medical devices such as insulin pumps are vulnerable to security breaches, which places connected biomechanic and robotic devices in a uneasy space considering their functional capabilities are to assist the health of the seriously ill.