Youth social networking researcher danah boyd has observed that many people presume the way they use social networks is the way everyone uses them. “I interviewed gay men who thought Friendster was a gay dating site because all they saw were other gay men,” she says. “I interviewed teens who believed that everyone on MySpace was Christian because all of the profiles they saw contained biblical quotes. We all live in our own worlds with people who share our values and, with networked media, it’s often hard to see beyond that.”

Now picture our perspective leaving our own experiences, zooming out and up until we can see how all the different groups are interacting on a worldwide social network. That bird’s-eye view could be both beautiful and horrible if the resolution was clear enough. That’s what a Ramen-eating, ex-Apple engineer named Pete Warden is about to release to the public this week.

This Wednesday, Warden will make Friend, Fan page and name data from hundreds of millions of Facebook users available to the academic research community. It’s a move that Facebook has to have seen coming, a move that many in the data-centric community have been calling on the company itself to do for years, and an event that’s been complicated by Facebook’s recent privacy policy changes, which have muddied the waters of right and wrong but rendered even more data available for outside analysis.

If what people call Web 2.0 was all about creating new technologies that made it easy for everyday people to publish their thoughts, social connections and activities, then the next stage of innovation online may be services like recommendations, self and group awareness, and other features made possible by software developers building on top of the huge mass of data that Web 2.0 made public. It’s a very exciting future, and Warden is about to fire one of the earliest big shots in that direction.

Nerds in Space: Social Graph Analysis For Solving Large-Group Problems

Warden studied Computer Vision in college in the U.K., then got into game development. After moving to L.A., he spent six years building graphics drivers for the original Playstation and the XBox. Then he started his own independent business, where, thankfully, he open-sourced much of his work (something he’s still doing today).

When he found out that starting his own business wasn’t going to work with his immigration status, he was very fortunate to have also caught Apple’s eye with the software he had been releasing to the public. Apple bought his company in order to bring him on board. The proceeds of that small sale are now sustaining his next project after going independent again.

After spending five years at Apple struggling to navigate the maze of people and connections and types of expertise in order to get the information he needed, Warden decided to go independent and build a company that solved exactly that kind of problem. “I can’t think of a better big company to work for, but it was still a big company,” he says. “It was hard to find the right people to talk to, whether for particular expertise or for contacts at external companies.” And so Warden left Apple to build a company that would use social graph analysis to solve problems like that. He called the company Mailana, a play on “mail analysis” since he was initially focused on email social graph analysis.

We’ve written here a number of times about Mailana’s tool that analyzes the social graph of any Twitter user. Enter the username of someone on Twitter and Mailana will show you which 20 other people the user has exchanged the largest number of reciprocal public @ replies with. Find someone interesting or important? Mailana’s Twitter analyzer will tell you who they most regularly interact with. See, for example, The Inner Circles of 10 Geek Rockstars on Twitter.

Pulling Down the Facebook Social Graph

Now Warden is about to unveil a much larger project along the same vein. For the past six months he’s been crawling public profile pages on Facebook. He now has more than 215 million of them indexed and updated about once a month. When he began he was using the Web crawling service 80legs, but over time he had to build his own crawling infrastructure.

When I talked to him this afternoon, he had already begun uploading 100 GB of user data onto his server to make it available for academic research starting on Wednesday. Warden says he’s removed identifying profile URLs but kept names, locations, Fan page lists and partial Friends lists. All those fields of data are just waiting to be analyzed and cross referenced. That’s one very rich resource.

Yesterday Warden posted some of his own initial observations from the data on his personal blog. Those included:

- In almost every state in the Southern U.S., God is number one most popular Fan page among Facebook users. Among people in the L.A., San Francisco and Nevada regions? “God hardly makes an appearance on the fan pages, but sports aren’t that popular either,” Warden writes. “Michael Jackson is a particular favorite, and San Francisco puts Barack Obama in the top spot.” In the Oregon and Idaho region? Starbucks is number one.

- In the Mormon-influenced areas of Utah and Eastern Idaho, the most popular Fan pages are The Book of Mormon, Glen Beck and the vampire book Twilight, which was authored by a Mormon.

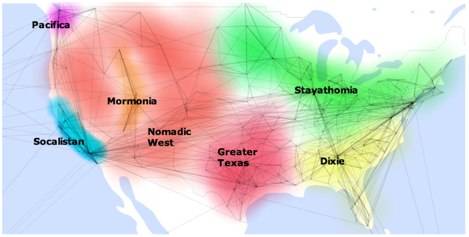

- The bulk of Warden’s posted analysis yesterday was about location networks. People in the western U.S. tend to have Facebook friends all over the country; people in the southern U.S. tend to mostly be friends with people who have remained in the same area.

Taking a Deeper Look

These observations are interesting, but they are only the beginning of what’s possible. Name, location, friends and interests are great data points to analyze. Warden has written a program that will estimate gender as well, based on names. All these data points can be cross-referenced with outside data, too. Members of Facebook’s own staff did this kind of analysis when they compared user last names to U.S. Census data, which allowed them to estimate changes in Facebook’s racial composition over time based on the likelihood of people with particular last names to report a particular racial backgrounds.

“I’m mostly thinking ‘What do I try first?’,” Warden says. “There’s so many interesting ways to slice the data – especially as I’m starting to get changes over time. I’m also trying to map out political networks in aggregate; how polarized the fans of particular politicians are – so how likely a Sarah Palin fan is to have any friends who are fans of Obama, and how that varies with location too. One of my favorite results is that Texans are more likely to be fans of the Dallas Cowboys than God.”

Warden says he hasn’t talked to anyone from Facebook since he started crawling the site, but he did get an email from someone on the security team asking him to take down instructions he’d posted that exposed a security hole that made harvesting peoples’ email addresses easy. So the company is paying attention. “I’d love to see them put me out of business by putting decent data out there,” Warden says. He says his Amazon Web Services bill was over $5,000 last month.

Why is he indexing all this content and why is he going to hand it over to the academic world later this week? “I am fascinated by how we can build tools to understand our world and connect people based on all the data we’re just littering the Internet with,” Warden says.

“Nobody thinks about how much valuable information they’re generating just by friending people and fanning pages. It’s like we’re constantly voting in a hundred different ways every day. And I’m a starry-eyed believer that we’ll be able to change the world for the better using that neglected information. It’s like an x-ray for the whole country – we can see all sorts of hidden details of who we’re friends with, where we live, what we like.”

For a great example of the kind of social impact that data analysis can make, Warden points to some of the fascinating ways that GIS data is illuminating the intersection of race and public services. Data has shed light on social injustices for decades, and measurable information about the interactions of hundreds of millions of people every day on Facebook offers opportunities to discover both good and bad news about the contemporary human condition.

Warden says he’s not yet been able to interest any investors in his ideas for businesses based on this data, so his girlfriend Liz Baumann, a former insurance actuary, stepped in to help and is now running much of the crawling. He says he’s now focused on “working on ways of presenting all this information in a form that answers questions for people willing to pay.” His first experiment along those lines is the very interesting FanPageAnalytics.com.

What does Pete Warden hope for from this week’s public release of all this Facebook data? “Hopefully I’ll get to see a bunch of interesting [academic research] papers come out of it, worst case. And I’d like to be the guy people turn to when they need stuff like this.”

Already well-respected among a fringe group of bleeding-edge geeks, we hope that Warden’s work on social graph analysis will end up impacting a far larger number of people than may ever know his name.