Twitter is looking into making TV shows. That direction would have been unimaginable four years ago. But the Flock has made its nest. Twitter is a media goose that wants to lay a golden egg. And entrepreneur Dalton Caldwell doesn’t believe the company can squeeze it out.

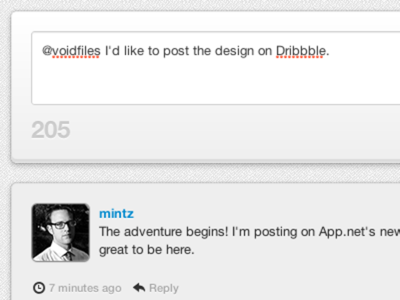

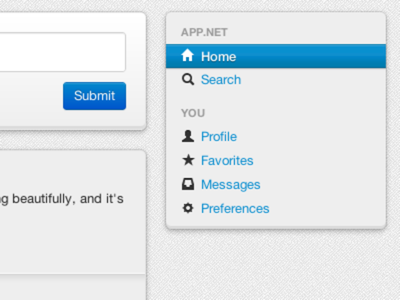

Caldwell is building App.net, which he calls a “real-time social feed without the ads.” He wants a Twitter-like service that acts as infrastructure, the “dial tone for the real-time Web,” not an advertising vehicle with a captive, chattering audience.

ReadWriteWeb caught up with Caldwell in his office on Wednesday, just after Zynga, maker of those addictive games on Facebook and elsewhere, announced its miserable quarterly earnings. “I’ve seen this movie before,” Caldwell said of the ad-based social network landscape. Twitter and Facebook have grown large enough that they’re able to make money from socially targeted advertising, but neither has found the formula that will generate enough cash to build a lasting business. “At the end of the day, a crap ad impression is a crap ad impression,” he says.

Caldwell tried the brute-force ad approach himself at imeem and picplz. It didn’t work. He couldn’t mine enough money from these kinds of social media. Facebook and Twitter have ascended on the promise that they can. Caldwell doesn’t buy it.

Twitter’s Chilling Effects

Twitter hasn’t made its strategy entirely clear, but recent actions and statements strongly suggest that the company intends to close off its tinkerer’s paradise, open for all to invent diverse experiences out of the service’s core capabilities, and funnel users into the official Twitter apps. These apps are optimized for the newest features, which deliver rich media experiences designed to hold users’ attention while Twitter shows them ads.

The warning signs are everywhere. Twitter has been beating the drum about cutting off the third-party apps responsible for roughly a quarter of its content. It’s doing so in the name of consistency – ostensibly to standardize the Twitter experience.

“You need to be able to see expanded Tweets,” Twitter Product Manager Michael Sippey wrote in June, referring to a rich-media feature that only Twitter’s official apps currently display.

And Twitter’s axe has begun to fall on third-party developers. In May, Kara Swisher at AllThingsD reported that Flipboard CEO Mike McCue might leave Twitter’s board. Swisher’s sources explained that McCue has begun to feel “that the companies are on a product collision course.” Since Twitter’s latest moves are all about corralling users within Twitter’s walls, the conflict with Flipboard, which repackages material from a user’s Twitter stream for personalized browsing, seems obvious.

In June, on the same day Twitter delivered its latest warning about closing off its ecosystem, LinkedIn announced in a mournful blog post that Twitter had cut off the ability for LinkedIn users to automatically publish their tweets as LinkedIn updates.

On Thursday, Instagram released an update in which the “find friends from Twitter” feature is broken. Instagram shows a warning message: “Twitter no longer allows its users to access this information in Instagram via the Twitter API.” Other, smaller services still have this access, but Instagram users are screwed.

Caldwell sees in these events the classic symptoms of an online media company failing to fly. “Media companies are starving,” Caldwell says, “and that’s why they do crazy things.”

Hot Dogs & Caviar

On his blog at daltoncaldwell.com – a must-follow if you’re interested in these issues – Caldwell framed the problem with an appropriately gross metaphor: hot dogs and caviar.

Here’s the story that Twitter – and Facebook, too, for that matter – is selling: The social messaging company will create some powerful new “social ad unit” that will turn the “hot dog” ad impressions currently annoying people who are just trying to talk to each other into “caviar” that tastes delicious and is worth lots of money.

That sounds unlikely to Caldwell. But Zynga and Facebook have already committed themselves to this direction. Twitter is another matter, because it doesn’t need to go this way.

At the beginning, “Twitter was the most open, radical, insane thing ever,” Caldwell says. “It was almost like an art project.” It just put this simple service out there, and its users and developers defined the features that built it into a massive service.

But “the ad guys won,” as Caldwell wrote before launching his App.net adventure. Now Twitter wants consistency and control. It wants to be a media company that others “build into,” not “build off” of.

“It makes me angry when I see businesses that are built on controlling bits,” Caldwell says. “Twitter is either going to destroy themselves and sell to Google or turn hot dogs into caviar.”

Caldwell doesn’t want to lose Twitter the service, even if he loses Twitter the company. So he proposes App.net as a business first and foremost, a model that will sustain a Twitter-like service and serve the interests of users and developers – that is, if it can meet its $500,000 crowdfunding goal.

What Is App.net?

App.net will be a paid service. Its members will pay an annual fee to be regular users. That means App.net has to keep them happy. It won’t advertise to them. It will let them own and control all of their data, so their privacy won’t be compromised. And they can leave at any time.

Developers who want to build apps for the network also pay for access. That means App.net has to keep them happy, too. It plans to do so by allowing them to build apps, extensions and businesses of their own on top of App.net’s managed, centralized service. They can even host their own, decentralized versions and just hook in at the end.

The service doesn’t exist yet. If you go to join.app.net, you’ll get the pitch, and you can back the project Kickstarter-style. The member tier costs $50, which covers the first year of service, and you can reserve your user name when you back the project. For $100, you get access to the developer tools, so you can hack on the service. The funding goal is $500,000, and it ends at 11:59 p.m. Pacific on Monday, August 13. At press time, it’s still shy of $100,000.

If App.net doesn’t meet its crowdfunding goal, well, it was worth a try. The backers keep their money.

But Caldwell is already talking to well known developers, both of client apps for users and for back-end feed technologies. He says they’re intrigued. If the campaign succeeds, the community will be pretty strong from the get-go.

Caldwell chose the $500,000 goal for its symbolic value, but it represents an important threshold of interest. 10,000 committed users would be enough to incubate the service by experimenting with features and social conventions, just like Twitter did at the beginning.

Reinventing the Stream

Twitter already demonstrated the underlying, world-changing idea: a real-time service for short, public messages where every user can contribute a feed to which anyone can subscribe. That’s vital. Twitter has thrived because people found the service useful, even necessary.

But eventually, Twitter the company had to figure out what business to be in. It decided on ad sales, squeezing money out of the attention paid by its users, which requires clamping down on the Twitter experience. Caldwell is far from alone in feeling disappointed by that decision.

There have been other attempts to build a Twitter-like service that works the way it “should.” Identi.ca is still up and running, but it’s hardly a developer’s playground. Without business reasons to build better experiences for the service, it will never grow up. Others don’t believe a centralized service can ever be a lasting solution. Dave Winer has offered a neat list of suggestions for how a decentralized messaging service can be achieved, though it has some technical drawbacks.

One obvious problem with a paid, centralized service like App.net is reach. Twitter is great precisely because anyone can be on it. A decentralized service built into the Web itself would expand the reach by allowing people to access it with any app they chose. As a paid service, App.net will be limited, and that kills off much of Twitter’s appeal.

But that’s what the developer ecosystem is for. If App.net can build a good home for developers, it can build the federation needed to reach the outside world. Caldwell’s model is GitHub. It’s based on a decentralized protocol that anyone can take advantage of, but there’s a premium, centralized, managed service that people use for the convenience and peace of mind.

The questions here are less about capabilities and more about motivations. All kinds of technologies can be used to build a new Twitter. But where is the organization that will actually do it?

By starting with a business plan, App.net has put the incentives in place. The product, if it gets funded, may not satisfy everyone. But that’s better than a perfect idea that never gets made.