Editor’s note: We offer our long-term sponsors the opportunity to write posts and tell their story. These posts are clearly marked as written by sponsors, but we also want them to be useful and interesting to our readers. We hope you like the posts and we encourage you to support our sponsors by trying out their products.

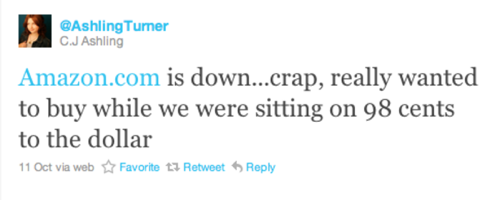

When Gmail is slow, Amazon trips, when there is a Facebook issue, or Foursquare’s API crashes, people get upset, and tens of thousands reveal their anxiety on social networks.

Every time there is a major outage, security issue, or malfunction we see this pattern of raised anxiety, doubts, and questioning of services in the cloud in general.

This makes perfect sense of course, as Web apps and Web services have become more prevalent and are now an essential part of our daily habits and work. The advantage of Web apps is compelling: simply grab a PC, iPad, laptop or mobile phone and you have everything at your fingertips. But there is a downside too: we become dependent on the cloud infrastructure and our connectivity to the network.

The reality is that software and services break. Desktop software normally breaks with one user at a time, although millions will be affected over time. If a Web app breaks however, hundreds of thousands are affected at the same time. There is also a psychological effect: when software on a computer fails, people often feel (partly) responsible for it. With Web apps, the provider is the only one to blame.

So even if Web apps are far more reliable than local apps – and I believe this is often the case – the public outcry is far more extensive. Especially now, when typing “#fail” on social networks like Twitter and Facebook, is only seconds away.

What does this imply for the companies behind the Web apps we use every day? The single most important thing is to have the communication channels in place well before a ‘crisis’ strikes.

I personally suggest having the following at minimum:

- A blog or status page that is hosted independent (and scalable!) from the main website and services. Easy, predictable, standard names should be used: blog.company-or-brand.com and status.company-or-brand.com, respectively. A good example: status.readwriteweb.com. Preferably these pages should include up-to-date, live, stats.

- A Twitter name where one can post quick updates. If possible @company-or-brand should be used here too. Example: @rww.

This first level of transparency makes it easy for people to get informed and immediately results in lower anxiety levels. This in turn, helps to stamp out rogue stories in times of crisis, and reduces the load on the company’s customer service contact center.

Many companies have set up public status pages already.

Next, when an outage or other crisis starts unfolding, these companies should make sure to cover the next points:

- Admit failure as soon as possible, preferably by someone high up in the organization

- Make sure the posts and updates sound human, no standard sound bites

- Explain in detail who and what is affected (which regions, percentage of customers, what services, etc.)

- Publish a detailed timeline of the outage, and start maintaining this immediately after the first event

- Share detailed post mortem reports and lessons learned after the crisis is over

- Read more here for a more detailed analysis of the psychology of transparency

If these guidelines are followed, the added benefit is that it actually induces and instills a higher trust in the company and its brand – not less. It also gets the message across quickly and efficiently, so it can then be relayed across social networks, instead of leaving it up to the guesses of the public or the media. Finally, it will save serious money in the company’s contact center, as it sets the right expectations.

Companies that are transparent about issues regarding their services will actually gain kudos and trust.

So the next time there is an issue with your favorite application on the Web and www.your-favorite-app.com is not working: you might want to check out status.your-favorite-app.com to see if there is up-to-date information before you type “#fail”. A Public Status Page may just be waiting for you there.

Stan P. van de Burgt is CEO and co-founder of WatchMouse, a company that monitors websites and services 24×7 from over 50 locations worldwide and delivers detailed insight about their performance, uptime, and functionality. Inspired by the dashboards of Amazon and Google, WatchMouse introduced Public Status Pages (PSP) in early 2010. Companies like Twitter, Mozilla, WordPress, and many more use this product to be even more transparent to their customers, users and developers.