Following the tragic Colorado shooting in Aurora last week, many Americans turned to social networks and the Internet to express their grief, offer condolences, or raise money for the victims. Trolls were no exception, and they too came out to play on this information highway.

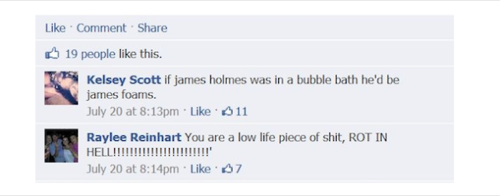

Shortly after the shootings, on July 21, a James Holmes Tribute page appeared on Facebook. The page included photoshopped photos of Holmes and a slew of jokes, such as rhyme games featuring Holmes’ last name: “If James Holmes were short, he’d be James Gnomes.” The page caught the nation’s attention with a plethora of press mentions, hand-wringing and speeches on the state of youth today. Facebook removed it on July 26 despite the fact that it did not violate Terms of Service.

But this kind of provocation, or trolling, may be more than it seems; it may be the social side of grief in a networked world. Whitney Phillips, a University of Oregon ethnographer who focuses on online media, concluded in a study published last year that RIP trolling is a “social critique on the way we live our Web lives.” Indeed, it’s hard to look at the commotion around the James Holmes Tribute page and not see layers and layers of social commentary, intentional or not. Posting on Facebook was an integral part of the national grieving process, from numerous memorial pages for the shooting victims to the sudden scramble to find Holmes’ real Facebook page. Mocking society’s addiction to Facebook would, of course, be best done on Facebook.

The James Holmes fan page that prompted the most public outcry was liked only 888 times but actively discussed by 3,000 people at all times. Holmes tributes in general were dwarfed by the dozens of Facebook groups calling for the death penalty for Holmes. Apparently it was more socially acceptable to call for the death of Holmes on Facebook than to give him a tribute page. Most egregious of all, apparently, was joking about the tragedy or its perpetrator.

On the tribute page in question, the most ferocious comments came not from trolls, but from angry users whipped up by the press coverage. Facebook users threatened to shoot the page’s creator, wished him or her a slow death, and generally behaved in a way that normal Internet watchers would mistake for trollish behavior.

“Wishing death on someone is [definitely] worse than making a harmless joke on Facebook” wrote Jadehh Munro in a Facebook comment thread, responding to angry users who threatened to kill the person who posted the tribute page.

It doesn’t matter where the dozen or so Facebook users behind the joking spend most of their time – 4chan’s notorious /b/ board, an Encyclopedia Dramatica IRC channel or a Something Awful forum. After the Colorado shooting, they came to this digital place, hung out, told jokes and laughed. Phillips advised against framing the page as “an emotional or coping mechanism” because “trolls motives may vary,” but, when you imagine the amount of time the Facebook creators spent making their pages, it’s hard not to think the trolls were grieving in their own way.

Of course, that doesn’t make the jokes polite or tasteful. “It’s important to place these sorts of transgressive behaviors in context, but it’s also important not to sugarcoat the behaviors,” Phillips wrote in an email. “They troll because it upsets people, and because they derive amusement from their targets’ distress. National tragedies are a perfect opportunity to capitalize on heightened sensitivities, and so that’s precisely what they do.”

But free speech covers impolite and distasteful statements. And on Facebook – if the site will allow – we can all grieve together.