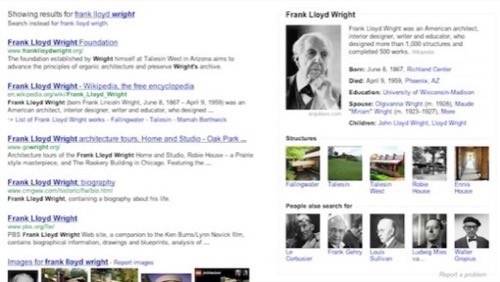

In May, Google launched a major overhaul of its search results. The Knowledge Graph on the right-hand side of the page displays facts and images about the subject of your query alongside the usual Web results. Google is moving away from basic keyword matching and toward recognizing real-world things and their relationships. We sat down with Emily Moxley, Google’s lead product manager for the Knowledge Graph, to learn how Google is tackling this challenge.

ReadWriteWeb: What is Google’s goal with the Knowledge Graph?

Emily Moxley: It’s about mapping the real world into something that computers can understand. It’s all about taking real-world objects, understanding what those things are and what the important things about them are, and also their relationship to other things. That’s the part I find the most fascinating: What is the relationship between all these different things?

RWW: How did you come to work on the Knowledge Graph?

EM: I’ve been here for three years, and I started off working on user experience, running lots of experiments and understanding how users scan the page and how they really use search. That culminated last summer in a page redesign. As part of that project, we came up with this product idea of the Knowledge Graph.

RWW: Is the Knowledge Graph idea as recent as last summer?

EM: It’s building on stuff that’s been developed for quite some time. Freebase [semantic database software] and [its publisher] Metaweb have been around for five years. We bought them two years ago. It’s been building off of that. We took the data they had, packaged it into this [Knowledge Graph] UI, and it shows on many more queries than it ever has before. It shows on as many queries as Maps shows on.

RWW: How do things get added to the Knowledge Graph? Does it learn new concepts from users?

EM: It’s very actively maintained by Google employees. Metaweb, before, was this repository of entities and facts, and [the company’s employees] were very much using their intuition about what people cared about and what information to go find. Since they’ve been acquired by Google, Google has all these users looking for information, and from that, we’re able to see what things are interesting about the world. Through that, we’re able to grow the Knowledge Graph in an efficient direction. We usually find that the users’ interests match our intuition, but there are serendipitous things that wouldn’t necessarily match your intuitions. Google knows that people who query for one thing also query for this other thing. So you see some interesting relationships when you look at aggregated user sessions. One of the next steps is actually explaining those serendipitous relationships. So what is it about this collection of actors that’s similar among them? What is it about this movie that explains why people often search for these five movies together?

RWW: How does news or new information play into this? When things change, how does the Knowledge Graph change?

EM: This is a case where we’re able to tap into a number of different signals that tell us this thing is popular right now. Search is one of them, Google News is another. These tell us something’s going on here, and we need to take a look and possibly make a change. The other way is through user feedback. We tried to create a very easy user feedback mechanism and tap into the things that our users know. That’s something we can do at such a big scale that we’re able to correct a fair number of things that way. We measure ourselves, and we do quite well, but we know we’re not going to be perfect, so we rely on people letting us know when we have something wrong.

RWW: Is working with third-party data sources, like the CIA World Factbook or Wikipedia, more challenging than working with Freebase data?

EM: There is one really big challenge with using all these third-party data sources, and that is the reconciliation. Even internally, we just acquired Metaweb two years ago, and we already had massive amounts of data in certain areas, books and local maps data being two of the major ones. Both of those were far bigger than Freebase was, even when we acquired them. They had far more entities and information. Reconciling those with the new data sets was a major challenge. So reconciling those third-party data sets with the Knowledge Graph is a challenge, but it’s also something that Google is quite good at, these big-data problems. It’s no more difficult with third parties than it was with internal stuff.

RWW: But do you have to correct things sometimes? How do you determine your confidence about whether the CIA World Factbook is right or Google is right?

EM: We purposely try to show things that are definitely true – factual – not things that are subject to speculation or opinion, and we err on the side of facts. So if it becomes controversial, we might decide not to show it [in the Knowledge box]. We provide an externally available feed of updates that we’re making in Freebase. They’re supplied as potential edits to Wikipedia editors or things like that. The third parties have the choice of whether to update in response to these or not. We haven’t encountered any huge problems as far as validating new information from third parties.

RWW: The Knowledge Graph seems like a big change to search. It’s providing more results right on the search page instead of sending users to websites. What happens to the Web?

EM: Typically, Google’s goal has been to get users off the site and to their destination as quickly as possible, and I do think that, with Knowledge panels, the goal is different. It’s about getting information as quickly as possible, but it’s also about providing things you didn’t even know to look for. If you’re looking for a quick fact, and we can supply it, that’s great. If you’re looking for more in-depth information, that’s something we currently can’t do terribly well, and that’s why we provide ways to refine your query [and then direct you to Web results]. We think that webmasters and websites will ultimately benefit from that, if we’re able to direct users to the good content they’re actually looking for.

RWW: What kinds of searches do you still need to implement?

EM: Today, we address what I would call single-entity-seeking queries. In the future, we’d love to be able to address queries that are more about lists and collections. “What are the tallest mountains in India?”, or “What are the largest cities in the U.S.?” In order to understand that query, we have to understand cities, then we need to understand the U.S., then we need to understand that “largest” can refer to either population or area, and then we come up with a comprehensive list. Then we could get to something even more nuanced, like, “I’m looking for concerts within 50 miles of me on days when I’m free where it’s likely to have good weather.” That sort of thing requires tapping into more knowledge of the user, as well as all of this information.

RWW: What interests you most about this project?

The serendipity and discovery aspects are always interesting to me. The other day, I was looking at the [results of a] San Francisco query, and one of the points of interest mentioned was Angel Island. I clicked on Angel Island, and I saw this [“people also searched for”] recommendation offered for Ellis Island. It meant to me, “Wait a second. It can’t just be that these two things are islands. I’m guessing there was an immigration station at Angel Island.” And sure enough, I went and looked and discovered that. That’s what’s exciting to me about Knowledge Graph, and if we can ultimately explain those relationships to users, that’s when it becomes even more inspiring.