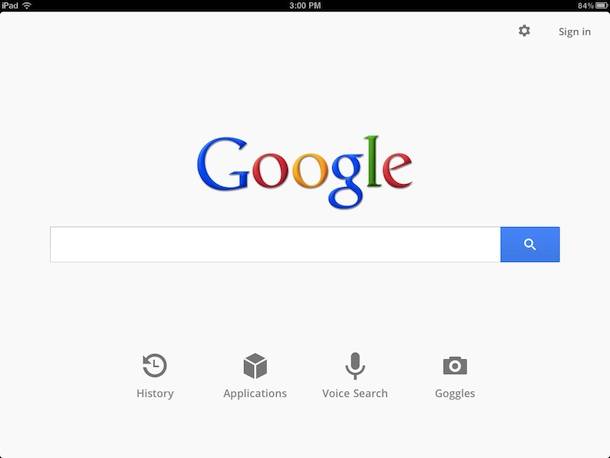

The design of the search page on Google.com is one of the most iconic in the Web’s history, but it’s in the midst of major changes. Google has redefined itself with Google+. Its notion of Web search as an index of pages has grown to include people, places and things. In addition to the search box, the page now has a share box. It takes great design to introduce all these new features and interactions to Google’s hundreds of millions of users.

At the same time, smartphones and tablets are changing the way users interact with the Web, and Google has to make that leap along with them. It has to strike a delicate balance between simplicity, consistency and usefulness. Fortunately, Google’s hundreds of millions of users provide mountains of data its designers can use to guide their decisions. I sat down with Jon Wiley, lead designer of Google Search since 2010, to learn more about how Google pushes its user experience forward.

ReadWriteWeb: What was your first search project at Google?

Jon Wiley: [T]he redesign that launched in early 2010. It introduced some of the additional tools for refining and filtering, and we launched a number of changes that simplified the results page.

Over time, we’ve also worked on a number of features and interactions, particularly Instant. Instant is probably one of the best examples of extreme power having to boil down to simplicity.

RWW: How much of that is on you as the designer, and how much of it is engineering? What’s the process for bringing a Google Search product or feature to life?

JW: We have a saying, which is “Don’t break search.” If you think about Instant, the basics of what you do in terms of searching on Google still work. You go to Google, you begin issuing a question or a query, you see whether or not you’re getting the results you’re looking for, and you make decisions about that.

That basic experience continues to exist. The difference is that we’ve made it a lot faster.

We do a lot of user research, and we run a lot of experiments. The user research spans a pretty big spectrum. On the one hand, there’s a lot of generative, evaluative research. We go out into the field, talking to people, figuring out what kinds of questions they have about their world. What are things they want to know that we could provide as a search experience?

“When you do something wrong, people notice it, and they remember it. When you get it right, you’re fitting in with their expectations.”

We [also] have research labs here on campus, and we invite users to come in and use the product. That’s much more qualitative research. Are we actually solving the user’s problem?

In the case of Instant, it was actually really interesting. When we were building the demos and walking through the process, a lot of people were really concerned about it. If you think about it, you start typing your query and suddenly the page changes. As fast as it was in terms of speeding up the conversation you have with the search results, we worried it was going to be distracting.

But it was actually really surprising. When we brought users in – and we just let them use the product; we didn’t really say anything about it – they would use Google search with Instant turned on, and after a moment, we would say, “Okay, well, tell us about your experience,” and they would say, “Well, I dunno, it’s Google.”

RWW: Users notice slow. They don’t notice fast.

JW: Exactly. When you do something wrong, people notice it, and they remember it. When you get it right, you’re fitting in with their expectations.

New Kinds of Questions & Answers

RWW: How does a product decision make its way into the design process?

It varies quite a bit. Sometimes new features or product directions can come from within the design team. This gets back to what I mentioned about our more exploratory research, generative research. We might go out in the field and just talk to users and figure out what kinds of problems they might have.

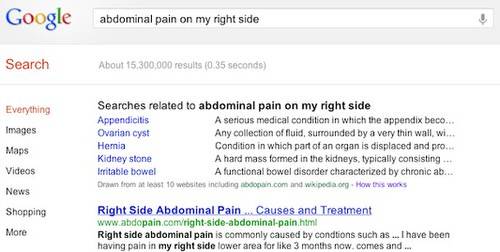

For instance, we did a study last year talking to people about questions they might have around medical issues. Medical queries [are] a really interesting space because there’s a high incentive to learn a lot of information. There’s a lot of judgment that has to happen in terms of the relevancy and quality of the content you can read on the Internet.

There’s an understanding issue, there’s all these issues around… [the user’s] awareness of this particular topic.

“We’re always continuously surprised by the kinds of questions people are asking and the kinds of answers they expect from Google search.”

There’s some social issues at work. I might be doing the research for a family member or a friend.

We try to identify ways in which we can better support the users with these types of information. Maybe there’s a gap where they’re trying lots of different tools, or they’re not aware of tools that are available them in terms of search. So we try to figure out ways… to make a better tool here or make it more discoverable.

From a design perspective, we can take all that research and start telling stories. From there, we can talk to engineers and product managers and work together to create a solution, and then again it goes through that iterative process.

It can also come from other parts of Google. In engineering, they can come up with lots of interesting ways of looking at information. The ranking engineers and search quality engineers are looking at the sessions, they’re looking at where people are having a bad experience or the ranking could be better, and a lot of times, there might be an algorithmic solution there. But sometimes there’s a design solution. There’s something you have to do in order to communicate to users, “Here’s a better path for you.”

For instance, the auto-completions or predictions that we have as you type, we actually had that well before we had Instant. There’s a lot of algorithmic power that drives it. And there’s a lot of ways we can represent that to users in the UI. That’s where we partner up [with engineers] to create an experience that’s going to be simple and easy to use.

A lot of times, engineering might come with prototypes that express the idea that they have – “Problem, solution. Here it is.” – but it’s not always presented in a way that’s intuitive. So we partner with them to create something that is simple, intuitive and beautiful as well.

“I think of search as a conversation. Our users come to Google, and they ask questions, and Google has to respond. There’s a dialogue that happens there, and hopefully that dialogue turns into an answer.”

I think of search as a conversation. Our users come to Google, and they ask questions, and Google has to respond. There’s a dialogue that happens there, and hopefully that dialogue turns into an answer.

This Is a Paradigm Shift

RWW: How did this process work for Search, plus Your World?

JW: There’s long been a feeling that search is not done. We’re at the very beginning of the search experience.

Google can answer questions a lot better if it knows a little bit about what you’re trying to ask it. One way [it can understand better is if users] hyper-specify the queries: “I’m looking for pizza near downtown San Francisco” or what have you. But we want to also save you time, let you ask a question and just naturally get the right answer.

With Search, plus Your World, we realized that we can provide great search results if we have some notion of identity, if we have some notion of connection.

This is a paradigm shift. This is a completely different way of looking at search. We talk a lot about people asking more complicated and deeper questions, but this is a whole other level.

What you’re seeing, from a UX perspective, is an attempt to introduce something that is rather new. It’s a new way of looking at things. Sometimes we want to over-communicate in the UI. You’ve changed something, you’re changing expectations, you may be changing behavior. So you look for ways to try to communicate this.

But in the long term, I think we have to see how people use it. I think we have to see how users respond to it over time. The same is true even for something like Universal. When we launched Universal, we had no idea. We had our initial tests, we had our initial user research and internal dog food, but how that feature would evolve over time, we just could not have predicted it. And now, Universal is part of the foundation of how Google works. It was transformative at the time. Suddenly, you’re getting these different kinds of Web results for these different intents you might have. That’s where we’re at with Search, plus Your World. We’re at the very beginning.

No Such Thing as an Average Google User

RWW: Have people chilled out about it since it shipped?

JW: [Laughs] That depends on whom you ask.

RWW: I’m not talking about tech bloggers.

JW: Well, saying “Have people chilled out” sort of implies that they were not chill to begin with.

RWW: Ah, well, I guess I am talking about tech bloggers, then.

JW: [Laughs] The truth is that there’s no such thing as an average Google user. We serve hundreds of millions of people throughout the world. The more common response from those who have the feature and have been able to take advantage of it is a lot like what we saw in our user research. It’s generally along the lines of, “Wow, this is cool. This is helpful.” We get a lot of that reaction from users.

Just to be honest, I hate to say that I could change one thing about the search results page, and I guarantee you that there will be someone somewhere that is unhappy about that change. It’s just the nature of the software business. And even a tiny, tiny fraction of people who are unhappy with a given feature or a given change that we make, in Google numbers, that can be a large number of people. So we try to listen to the minority voices as much as we listen to the majority voices and try to balance those.

But so far, I guess I would say that Search, plus Your World is working as intended. A large number of people who have the feature have derived value from it. Like I said, it’s got a long ways to go, but that’s true of any innovation that we launch.

Good Ideas Can Come From Anywhere

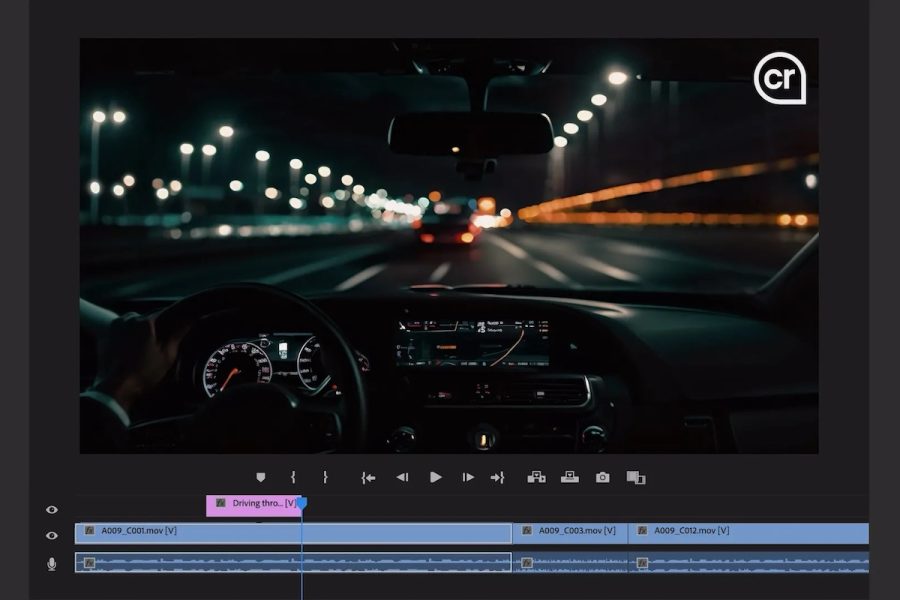

RWW: How do design decisions about search trickle over to the various interfaces such as mobile or tablets?

JW: In terms of product development, good ideas can come from anywhere. We’ve had feature developments and design developments that have happened in the mobile space. Particularly in the mobile space, actually, because it’s such a new environment.

The proliferation of these touch devices, the kinds of experiences people can have with these devices and the new ways in which they’re interacting is a fertile ground for creating some design innovations. We might look at that and say, “Wow, that’s actually really cool! Why don’t we see if we can carry that over to some of the other environments?”

“On the one hand, it’s a really challenging problem to design for, but that’s kind of the fun part about working for Google.”

I think touch screens are going to really proliferate. I think you’re going to have a lot of touch surfaces in a lot of places, and it’s going to be interesting to see how people interact with multiple modes of info. We have voice input on Google Search, you can drag a photo into the Google Search box, people are going to have keyboards and mice, but they’re also going to be able to touch the screen in multiple different ways.

There’s an aspect of it that’s a designer’s nightmare. It’s like the browser wars. There’s a multitude of devices, a multitude of browsers, a multitude of form factors, a multitude of conditions under which people are operating. Their location might be really important in one context and less important in another. All these variables are super-complex to deal with.

On the one hand, it’s a really challenging problem to design for, but that’s kind of the fun part about working for Google.

Everything’s a Trade-Off

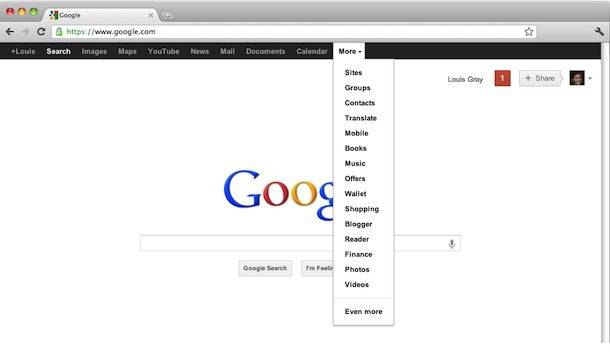

RWW: I want to know more about the changes to the main toolbar that have been happening recently. It keeps changing and changing back. What’s going on there?

JW: As a designer, I love this, because it’s a really hard problem, trying to figure out a way in which you can create a discoverable, usable, simple mechanism of navigating between services and applications.

In design, we say “Everything’s a trade-off.” You have a number of dials, and you can turn a bunch of them. One of the dials that we talk about a lot is discoverability. If I turn the dial way up on discoverability, it might be a giant button that says ‘Click Here.’ If I turn that dial down, it might be something like progressive disclosure. You take something and tuck it in under some other space.

In working through this, it was a classic kind of design process at Google where we went through a number of designs, we settled on a few iterations, and we ran a few experiments like the one you saw a few months ago. If we run an experiment large enough, we want to tell everybody, “Hey, we’re doing an experiment.”

One of the great things about working on products at Google is that we can try stuff out and launch it as an experiment and get tons of data. As a designer, I feel very lucky because I have access to enough data and enough users that I can actually get statistically significant information on whether or not something should be this tall, or this tall, or this tall.

Some designers, it drives them mad. But I think, if you knew that this mock-up is actually, objectively a better experience for people than this mock-up, you’d totally take that.

On the toolbar, this is actually a very complicated design problem. One of the dials that you’re turning is making it a functional, useful, discoverable tool. But other dial you’re turning is that you want to make sure you have enough space on a variety of devices and screens to make sure that the application [the user] is in is given as much space as possible.

Sometimes these trade-offs come into conflict. We have to do a lot of designs, a lot of experiments, a lot of iterations, and so in this particular case, we’re in the middle of that process. We’re trying some stuff, we’re looking at it, we’re seeing how it works, taking that learning, walking it back and iterating on that set of designs.

“I think, if you knew that this mockup is actually, objectively a better experience for people than this mockup, you’d totally take that.”

We’re pretty open about what we do, so we iterate in public a lot and try different things out. This is what happens on search in particular. We’re running tons of experiments all the time to tweak and fix and change.

My parents will be like, “Well… what do you do? Because search seems to be the same most of the time.” And that’s actually the best thing they can say to me, because I know it’s getting better, I’ve got the experiment data to prove it. If, the entire time, everybody’s going, “Hey, it’s working!” then that’s gold. People notice things when they break, but they don’t really notice things when they’re going well.

Abstract art image by Reinhold Leitner courtesy of Shutterstock

Correction: The article initially stated that Wiley has been the lead designer of Search since 2007. He has been at Google since 2007, but he joined search in 2010.