I promise I didn’t write this in advance, waiting for the appropriate moment to unleash it from the vault of pre-conceived, pre-digested stories about the deceased the way one fills in the Free Space in the middle of “N” on the Bingo card. When people would ask me, what will you write when Steve Jobs dies, I declined to answer because I didn’t want to think about it. I sincerely believed if anyone could beat pancreatic cancer, it would be him.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series we call Redux, where we’re re-publishing some of our best posts of 2011. As we look back at the year – and ahead to what next year holds – we think these are the stories that deserve a second glance. It’s not just a best-of list, it’s also a collection of posts that examine the fundamental issues that continue to shape the Web. We hope you enjoy reading them again and we look forward to bringing you more Web products and trends analysis in 2012. Happy holidays from Team ReadWriteWeb!

I hear the three words, “He gave us…” as a jump-starter, or what Steve Wozniak would call a “bootstrap,” for sentences that precede a recitation of all the technology milestones presented to the world by Steve Jobs. Right off the bat, those three words are wrong. Steve Jobs did not give us anything. To presume that he did is an insult to what the man genuinely believed, and to the ethics and goals he personally championed from the beginning of his career.

Kids in garages

Apple was an empowering company. It empowered people to build the personal computer – to build it for themselves, to make it individual and adaptable. The Apple II, I wrote in 1985, is a box of promises. What had sustained its popularity and its magnitude to that point in time was its users’ belief in those promises. The fire that fueled that belief was sparked, kindled, and spread by Steve Jobs.

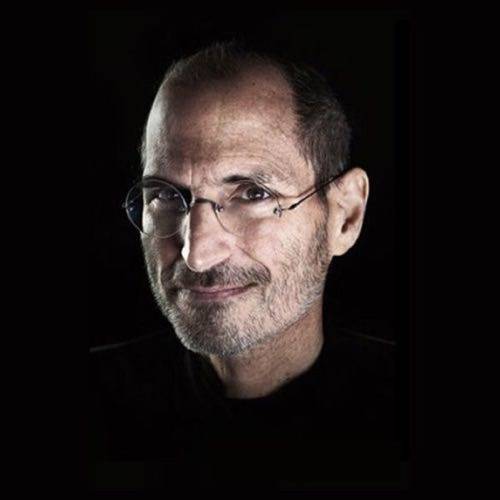

I blatantly leveraged his image to jump-start my career. The only way a kid as young as I was, as removed from the technology centers of the world as I was, and as flat broke as I was could ever hope to get in on the ground floor of the only revolution that America would see in the latter quarter of the 20th century, was to dress, look, and talk like one of those garage inventors. What amazed businesspeople back then – the type who would become my first clients – was that these wunderkinds, these Bill Gates and Steve Jobs-types, were so young, sure of themselves, arrogant, and could assimilate everything they touched.

Steve had a moustache, so I grew one too. I was 14, pretending to be 19. I looked like I was caught red-handed eating a Ding-Dong. But I looked enough like these smart, garage-inventor types to pull it off, wearing a tailored suit with a tweed jacket and the leather elbow patches. At the first computer conferences in the nation, I struck deals with the companies representing Apple. This was back before Apple had a national sales team big enough to cover the nation. Put me next to your computer, I bargained with them, and I’ll demonstrate to people how to use it. I’ll sell your Apple II, and you refer them to me as clients.

It was 1979. I lived and breathed Microsoft BASIC, and could diagram its statements and functions in every dialect, including Apple. I had developed a stump speech – what I’d say to people who looked at this thing and asked me, “What does it do?”

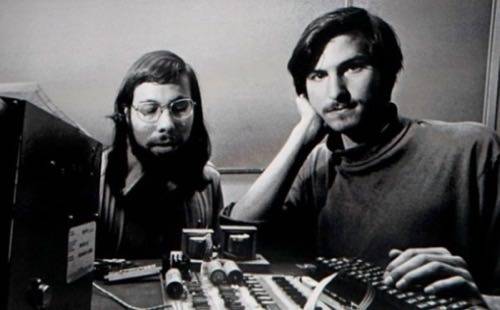

“Well, let me tell you, the two men who created this thing,” my speech began, “are named Steven Jobs and Steve Wozniak.” (“Steven” was his name back then; it was “corrected” later.) “Jobs is this guy who came from Hewlett-Packard, which is the company over there in the center aisle that makes those huge pen plotters. Wozniak is this designer from Atari. You’ve seen that home video game called ‘Video Pinball?’ He designed it.” That qualification impressed folks right away – a guy who could put a pinball machine on a TV.

“Anyway, they’d gone to some of these conferences a few years ago, and they’d seen the first home computers – the ugly ones in the blue boxes with the switches and wires – and they asked, ‘What does it do?’ And they’d get all kinds of responses, but nothing that had anything to do with what someone like you or me would want to do with it. So they built the first Apple I prototype in their garage, that’s why this one is called ‘Apple II.’ And what they decided was this: Let’s make a mass-production machine using HP standards and Atari construction. But let’s make it really, really programmable. So if you try something, even off the top of your head, you might be able to find a way to make it work. Here, let me show you an example.”

Then I’d do something mind-boggling for them, like write a Microsoft BASIC program right there on the command line, that calculated the distance between two points on a map. (It’s the Pythagorean Theorem, and I wish I’d patented it because I’d be a rich man today.) Then I’d plot a little graph for them in their choice of 16 fabulous colors. Ten minutes later, they were plunking down twelve hundred bucks for something they weren’t sure what it was, and I was handing out business cards.

A television ad produced by the store I consulted for in the late 1970s.

Containers for ideas

The things which the cable news anchors are saying Steve Jobs “gave” us (as if they were old enough to remember) are actually containers. They’re beautiful containers, but they’re open. They’re made for us to fill them – with information, with functionality, with the pictures and songs and dreams that remind us of who we are, or believe we can be.

To my knowledge, Steve Jobs invented nothing. As I’ve said here before, he was a brilliant businessman who could look into your eyes (and make you look deeply into his), and sell you on an idea. That idea, from the very beginning of Apple, was this:

You can make it work. It doesn’t have to be a multi-function gizmo box. You’re already smart enough and capable enough to make the box do what you need it to do. The box changed shape over Apple’s history – Apple IIc, Apple IIgs, Macintosh, Macintosh Plus, iMac, Power Mac, iPod, iPhone, iPad – and it was certainly exciting when the box got small enough to fit into the spare-change pocket of Steve’s Levis. But it was always small and big at the same time. And Steve’s idea of “scale” was that making it smaller made it bigger.

Icons and ideals

Fewer Americans than ever before in this country’s history are iconic symbols of something great and powerful. Folks today stare with sadness at the “HOPE” poster, and wonder what it was they had conjured in their minds that made it seem so real. Icons (not the desktop kind, but the ones that take human form) are often full of other people’s hopes, but they usually don’t keep there for very long.

There are many falsehoods being attributed to Steve Jobs – that he “invented the personal computer,” that he “dreamed of the mouse,” that he “created graphical computing,” that he “made the first tablet PC,” I’ve heard all these things just tonight. Clear away all the false attributions, erase the whiteboard of all the things “he gave us.” Let there be, for one moment, just the man, devoid of the stuff. What did he do?

Well, let me tell you. For an entire generation of young Americans who had every reason to believe what they were being told by their teachers, their friends, their bosses, even their family – that their dreams and ambitions were unattainable and that we were just cogs in a great machine we could never understand – Steve Jobs was living, breathing, human proof that it was all wrong. We were all vessels for something greater, we had it within ourselves to put on a game face and stand up to everything and everyone. He was the personification of “Hell, no!”

The gauntlet

On a cheap plastic TV in the middle of an Oklahoma art studio, my friends and I watched the 1984 Super Bowl. We weren’t interested in the football; I don’t even remember who played. We had known in advance about that ad, because the firm I consulted for gave me a heads-up. We watched that gorgeous blonde girl (great choice there, Ridley Scott) hurl that gauntlet. But we knew it was Steve who guided it right up Big Brother’s nose. We cheered louder than for any touchdown that had ever been scored. Three weeks later, I was a nationally published computing writer.

Steve Jobs did not give us anything. He challenged us, and his charisma and doggedness and determination not to let failure define him, made us respond. We know him mainly because of the things his company built, and mainly for his charismatic demos, which in the larger scheme of things is actually not all that much.

Take away those products and their demos as though they never existed, and what remains is the single best creation of his life, more valuable than anything Apple has ever produced. And right now, this moment, despite all that Apple has enabled me to do in my life, I would give it all for an eraser that could wipe out every Apple device ever made, in exchange for the one technology that matters this moment, in the here and now – or, better yet, 24 hours ago: the cure for his pancreatic cancer.

There are bigger problems to solve than can fit in an iPad. In his memory, we should revolutionize our approach to conquering death the way Steve Jobs revolutionized our approach to living life.